Recent years have seen a surge of hate crimes. Anti-Asian incidents have been especially frequent and unexpected. These encounters are reminders of awful behavior against Asians in Seattle and nearby communities during the 1860s-1890s, and after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Our history of racial violence warrants another examination, especially regarding Chinese residents, the largest group.

Attracted to America in the early 1900s by the promise of gold, a new life, and escape from restricted societies, migrants from China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and India used their savings and loans from families and friends to reach North America. The Gold Mountain beckoned, especially to Chinese. Within a few years after living in America, however, cracks in their dreams appeared: race prejudice, cheating employers, strange food, crowded and unhygienic living conditions, isolation from the larger society, and raw violence.

By the 1870s there were almost 70,000 Chinese in the United States, mostly in California. Chinese miners were particular targets of discrimination and violent acts. In 1852, California took official steps to target Chinese with a “foreign miners license,” aimed at taxing Chinese who did not wish to become American citizens. Long afterward, the federal Civil Rights Act of 1970 nullified that abuse, an act abetted by Chinese organizations challenging the string of anti-Chinese discriminatory laws and directives.

After gold-rush profits decreased in the late 1860s Chinese workers moved into other trades: laundrymen, weavers, domestic servants, and railroad builders. Many of the West’s dikes and irrigation channels were dug by Chinese, which led to the Chinese taking up agricultural work, especially truck farming. Mining, canning salmon, farming, and railroad construction attracted Chinese to the Pacific Northwest, where our “Gold Mountain” included precious metal discoveries in nearby Washington, British Columbia, eastern Oregon, and Idaho.

Chin Chun Hock is believed to be the first “permanent” Chinese resident in Seattle. Arriving from San Francisco in the 1860s, he did domestic work for a year, then founded the Wa Chong Company, a general merchandise house on the Seattle waterfront, and later owned the Eastern Hotel. Industrious and successful, Chin Chun Hock was able to counter a growing anti-Chinese sentiment among Euro-Americans, who saw their jobs threatened by hard-working Chinese willing to work for less, live in simple downtown clusters, and endure long hours in harsh conditions.

Murray Morgan in his history of Seattle, Skid Road, cites an 1880s Seattle newspaper story which claimed to speak for labor, in which the following descriptions of Chinese were employed: “scurvy opium fiend(s), “treacherous almond-eyed sons of Confucius,” “yellow rascals,” and “rat-eating Chinamen.” Signs appeared in Seattle that read: “The Chinese Must Go.” Clandestine committees were formed to plan the expulsion of Chinese from the Pacific Northwest. Citizens began to carry side-arms, and at one anti-Chinese meeting an ominous warning was issued: “We hold ourselves not responsible for any acts of violence which may arise from [non-compliance with our] resolutions.”

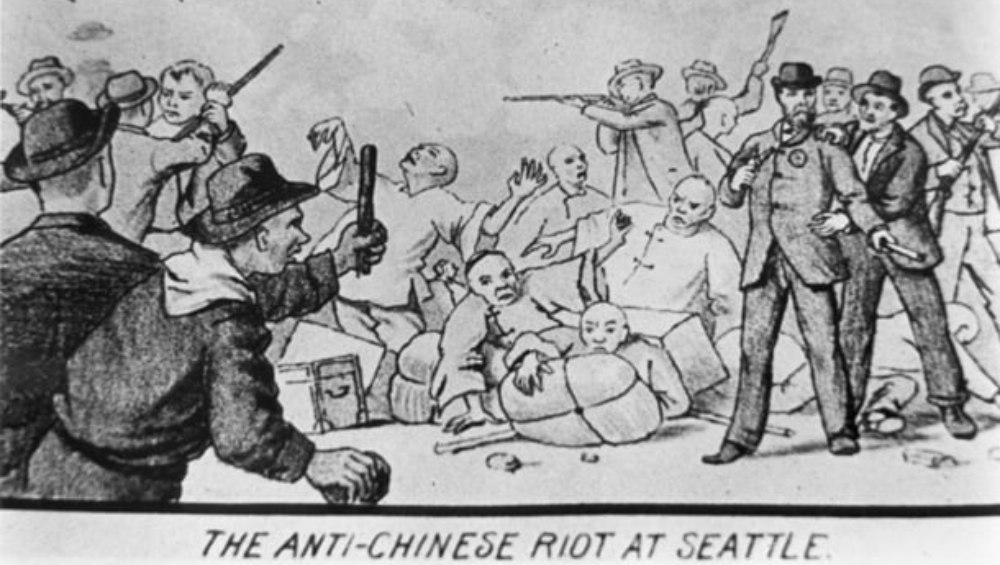

Seattle’s anti-Chinese actions were preceded by incidents in Rock Springs, Wyoming (two dozen Chinese killed), Issaquah (three deaths), and Tacoma, (roundup of the entire Chinese population for escorting to an outbound train). Smaller incidents occurred in Kitsap, Skagit, and Snohomish counties.

In September 1885, an “anti-Chinese Congress” was held in Seattle, which passed a resolution declaring that Chinese must leave Western Washington by November 15. Gov. Watson C. Squire asked the federal government to dispatch troops to Elliott Bay to ward off anticipated violent incidents and to detain several expulsion leaders. Before law and order took hold, 196 Chinese were forced aboard a steamer in Elliott Bay.

Soon there was a counter movement. Pioneer C.H. Hanford called a meeting at Seattle’s Opera House. A Home Guard was organized, and federal troops were placed on alert. Judge Thomas Burke spoke eloquently against mob action. U.S. Attorney W.H. White also attempted to calm the waters, followed by Gov. Squire’s proclamation to halt violence. Despite these efforts a so-called “Committee of Fifteen” advanced on the Chinese quarter, then located at Seattle’s Third Avenue and S. Washington Street, and threatened the residents. The vigilante committee managed to remove goods and engage in skirmishes.

Most of the Chinese were frightened enough to board a nearby ship, the “Queen of the Pacific.” At this point King County Sheriff John McGraw (later governor) sent the Home Guard to quarantine the ship. A sum of money was quickly raised to pay the fares of those who wished to leave. As the steamer filled with frightened passengers, the captain brought out the ship’s hose charged with hot water, and declared that forcing more passengers aboard would be dangerous. Nearly 200 Chinese departed for San Francisco, and another 150 were left onshore to board another ship due in six days. The remaining Chinese were threatened, and shots were fired, causing Gov. Squire to declare martial law.

It was said that most of the anti-Chinese agitators “left town.” Subsequent trials resulted in no convictions. The U.S. Congress appropriated $276,619.15 as full indemnity for losses incurred by the Chinese residents. As a final indignity the settlement was paid to the Chinese government, not to the injured parties.

The Chinese since reclaimed their honored place in Seattle’s life, helping celebrate the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, and relocating Chinatown eastward along Jackson and King Streets. Historian Walt Crowley later wrote, “By the late 1920s, when construction of the Second Avenue Extension uprooted much of the original Chinatown, a thriving neighborhood of Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino families and their American-born descendants was already blooming to the southeast.”

Chinese-American Wing Luke was elected to the Seattle City Council in 1962, followed by restaurateur Ruby Chow, who served on the King County Council 1973-1985.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.