Why the Washington Redistricting Commission melted down wasn’t clear when it happened, but now the silt is settling out of the murky water and the maps the commission kinda-sorta adopted have been released.

Based on discussions with knowledgeable sources in all four caucuses of the Legislature — the leaders of which appoint the commissioners — it seems clear the Senate’s majority Democrats essentially spurned a bipartisan deal by running out the clock on the commission’s authority to draw the maps. That’s a gamble on getting a somewhat better map for Democrats from the Washington Supreme Court, which now has jurisdiction.

Commissioner Brady Walkinshaw, acting on behalf of Senate Democratic leadership, repeatedly gummed up the end-game negotiations with last-minute demands and gambits, sources tell me. That led to a vote on a tentative plan just before the midnight deadline on Nov. 15. Crucially, the vote to submit the plan to the Legislature happened a few minutes later, early on Nov. 16, past the deadline in state law.

The following day, the commission acknowledged it had failed to adopt a plan and later released maps “approved” by all four members. It’s unclear what the court will do with them. The Supremes could just bless the commission’s maps, tweak them somewhat, or scrap them entirely and start over. They have until April 30 to produce a final plan.

Here’s why you should care. The commission’s process, including the meltdown, happened almost entirely behind closed doors, with naked contempt for the Open Public Meetings Act. Blowing the deadline, mandated by a system approved by the voters in 1983 for a bipartisan redistricting process, means the process was subverted and transferred to the nine Supreme Court justices, five of whom were originally appointed by Democratic governors.1 Significant amounts of the taxpayers’ money have been squandered. Regardless of which jersey you wear in this game, it’s not a good look.

Let’s take a look at those quasi-approved maps and the compromises they would have represented.

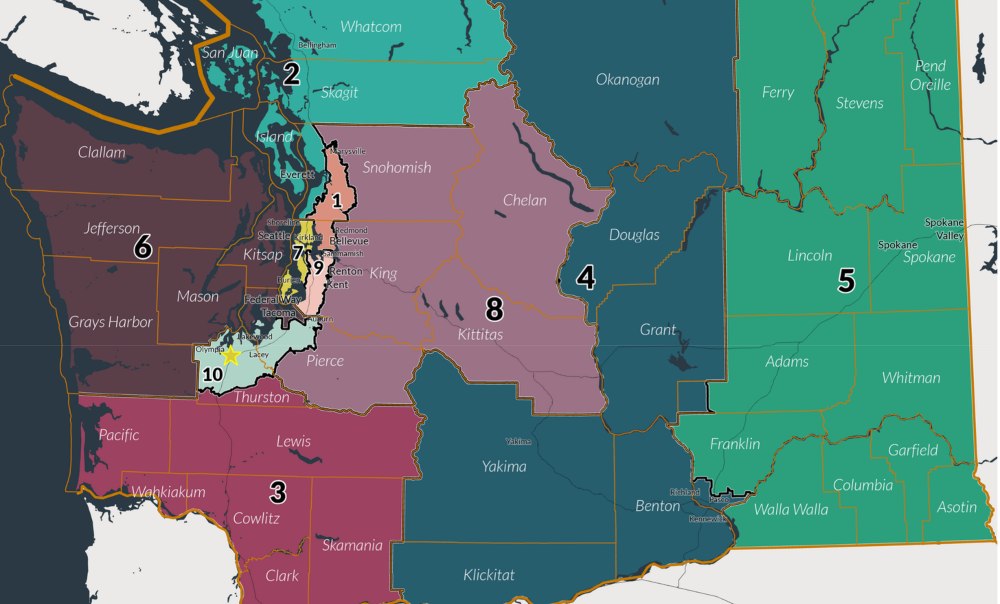

First off, the congressional map, which is simpler than the legislative map as there are only 10 districts:

For reference, here’s the current map, adopted by the previous commission in 2011. For the story of how that map got drawn, check out our piece from a couple of months back.

The big differences are in the 1st, 2nd, 8th, and 9th Districts. Here’s what the commission kinda-sorta agreed to do:

The 1st District, drawn in 2011 as a Republican-leaning swing district, but held since 2012 by Democrat Suzanne DelBene, gets conceded to the Democrats entirely. It contracts geographically, moving south into the increasingly dense and Democratic areas immediately northeast of Seattle, including Redmond, Kirkland, and Bothell.

The 2nd District, in northwest Washington, was drawn in 2011 to make Democratic incumbent Rick Larsen safe. The new arrangement takes over rural and conservative parts of Whatcom and Skagit counties from the 1st. Larsen’s likely still safe, but his district gets a little more purple.

The 8th District, drawn in 2011 to make then-GOP Rep. Dave Reichert safe, but won in 2018 and 2020 by Democrat Kim Schrier after Reichert’s retirement. In the new map, it gets somewhat more Republican in some interesting ways. It gives up some increasingly diverse turf in South King County to the 9th and pushes north to include exurban and rural parts of northeastern King County and the eastern two-thirds of Snohomish County. This is a variation of gambits offered by Republican commissioners Joe Fain, representing the Senate GOP caucus, and Paul Graves, representing House Republicans, in their initial maps.

The 9th District. Along with the 1st, Democrats get a safe majority-minority 9th District in southeast King County, redrawn to include even more voters of color than the 2011 version.

Elsewhere in the state, not that much changes. The 3rd District in Southwest Washington loses Klickitat County to the 4th District in central Washington, but GOP Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler is likely still safe. The 4th loses some territory in southeastern Washington to the Spokane-centered 5th District.

So what could the Supremes do to this map? A relatively small amount of scrambling could make the 8th completely safe for Democrats and the 3rd much harder for Herrera Beutler to hold. That could push Democrats’ margins from a shaky 7-3 to a solid 8-2. With control of the U.S. House on the line next year, there will be intense interest from the other Washington.

Now let’s move on to the map of districts for the state Legislature, which is both more complex and more contentious. The early proposed maps from the commissioners were aggressively partisan. The “final” map reflects some more subtle deal-making, much of it ultimately favorable to Democrats. First of all, let’s look at some entertainingly aggressive things that didn’t happen — at least not yet. Vashon Island isn’t carved off of the West Seattle-based 34th District, which makes Kitsap County’s 26th more favorable to Democrats, as Walkinshaw originally proposed.

Bainbridge Island isn’t sliced out of Kitsap County’s 23rd District and hitched up to a Seattle district, as proposed by Fain and Graves in a bid to pack the island’s largely Democratic voters into an already progressive district. Whidbey Island doesn’t get yoked to the San Juan Islands, as proposed by both Walkinshaw and April Sims, the commissioner representing House Democrats. That was part of a plan to create three safe Democratic districts in northwest Washington where just one — the 40th — exists today.

So much for what DIDN’T happen. Here’s some2 of what would happen in the new map:

The 12th District, formerly a solidly Republican district comprised of Chelan and Douglas Counties, sprawls across the Cascades to pick up a chunk of Snohomish County, making the perennially swing 44th District somewhat more Democratic. That’s the Senate seat recently put in play by Gov. Jay Inslee’s entertainingly machiavellian move to appoint Democrat Steve Hobbs as Secretary of State. The new lines would make it easier for the Democrat appointed to replace Hobbs to win next year. That’s likely to be Reps. John Lovick or April Berg, so Democrats would have an easier time winning an open House seat as well.

In Kitsap County, the commission sort of listened to arguments to unify Bremerton — currently split between three districts — into a single district. It’s now split between the 23rd and the 26th. More D-leaning Bremerton voters should give an incremental advantage to first-term Democrat Emily Randall, who faces a tough re-election fight next year against Republican Rep. Jesse Young of Gig Harbor. (The initial maps proposed by Democrats cut Young out of the district entirely and were more favorable to Randall.)

In South King County, the boundaries of the 47th District, lost by then-Sen. Joe Fain to Democrat Mona Das in 2018, get subtly tweaked to favor a Republican challenger to Das.

In Pierce County, the new map would make the 28th District more Democratic. T’Wina Nobles wrested the Senate seat in that district from Republican Steve O’Ban last year in one of the richest races in the history of legislative politics.

So why aren’t the Senate Democrats happy enough with this map to let it be the commission recommendation? Start with some background: After decades of political and legal fights over the issue, a supermajority of the Legislature and then a majority of Washington’s voters approved the bipartisan redistricting commission system to take the process out of the hands of the lawmakers themselves, becoming the third state to do so. Four voting commissioners are appointed by the four caucuses of the Legislature. It takes three to approve a map. So a deal requires a compromise.

That’s a sharp contrast from states where whichever party controls the Legislature gets to draw the lines. Check out my piece on gerrymandering that highlights how aggressive Democrats got in in Oregon a few weeks back. The Washington system requires a more subtle form of deal-making. We outlined how this is supposed to work in this article about how the 2011 map happened.

But there’s a problem. Many Democrats — in Washington and other states with similar systems — now have buyer’s remorse about these bipartisan processes. A deal with Republicans requires giving the GOP commissioners something they want, which many on the left believe they shouldn’t have to offer because most of the population growth in the last decade has been in Democratic areas of the state. The power to gerrymander suddenly looks tempting — especially in light of how aggressively Republicans in many GOP-led states practice that dark art.

I’ve heard several iterations from sources on the left side of the aisle: “I’m not going to be heartbroken if this winds up with the Supremes.”

For example, one of the biggest sticking points this year was over drawing a majority-minority district in south-central Washington centered around Yakima. The current lines are drawn to favor Republicans, with the Latino vote split between districts. The compromise map creates such a district, but activists argue it still violates the federal Voting Rights Act. Here’s that area in the compromise map.

The revised 15th District would have about 115,000 Latino residents, according to the commission’s analysis, but it leaves the Yakama Indian Reservation in the 14th District.

The logic goes like this: The Supremes, being judges, will follow the letter of the law instead of striking a political compromise. State statute dictates the map should minimize splitting up counties, cities, and communities of interest. In theory, that would benefit Democrats more than any compromise with Republicans, who want more competitive districts despite the state’s leftward shift.

So what will the Supremes do with this task, which they never asked for and likely don’t really want? Well, they might go looking for a map that checks the boxes in the law.

When he submitted his first proposed maps earlier this year, Walkinshaw took great pains to point out how compliant they were with those standards, prompting us to note that he might have drawn a blueprint with the Supremes in mind. He later revised the map with an aggressively drawn majority-minority district that looks like this.

Walkinshaw’s 14th District would have about 115,000 Latino voters, but it includes the Yakama Indian Reservation, theoretically increasing the likelihood that the district would send Democrats to Olympia.

It’ll be interesting to see how the Supremes react.

Footnotes:

1. The other four justices were elected to open seats. All nine have been elected statewide.

2. We’re undoubtedly missing many subtleties. Feel free to drop a dime, dear readers.

This story first ran in the Washington Observer, Paul Queary’s Substack newsletter

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I’m curious to know if

1. the Supremes will apply the open meetings rule to its own deliberations on redistricting?

2. why it’s legal to have majority minority Districts in the context of western Washington?