Seattle Parks grew from a 1884 city cemetery on Denny Way near the south end of Lake Union. That quiet five-acre tree-rich greenery was gifted to the city by David T. Denny, a city founder.

Soon, Seattle’s hills, valleys, rivulets, shorelines, and canyons, some with bascule bridges and wooden trestles, posed fearsome challenges to city planners and land investors. What to do? The plans and solutions soon multiplied and are memorably preserved in a quirky archive by Don Sherwood.

In 1892, for instance, Seattle City Parks Director E.O. Schwagerl, who had designed Tacoma’s Point Defiance Park, took on this challenge of natural and human-shaped features. He “made no small plans,” and his grandiose boulevard and park proposals were intended to reflect Chicago’s Lakeside Drive and the just-completed Riverside Drive in New York City.

That year also saw City Engineer R.H. Thomson designing the city’s first sewer and water systems, meant to serve a large city. He added the massive task of removing Denny Hill, which had blocked the city’s northern expansion to Lake Union.

Four years later, Seattle adopted a new home-rule charter, which turned over all management responsibilities of the parks to a Board of Park Commissioners, a remnant of which continues today. This newly-empowered group wasted no time in plunging ahead with a long-term program. Shortly, the commissioners would oversee 6,000 acres of parks, 20 miles of shoreline, and 22 miles of boulevards – virtually a city within a city.

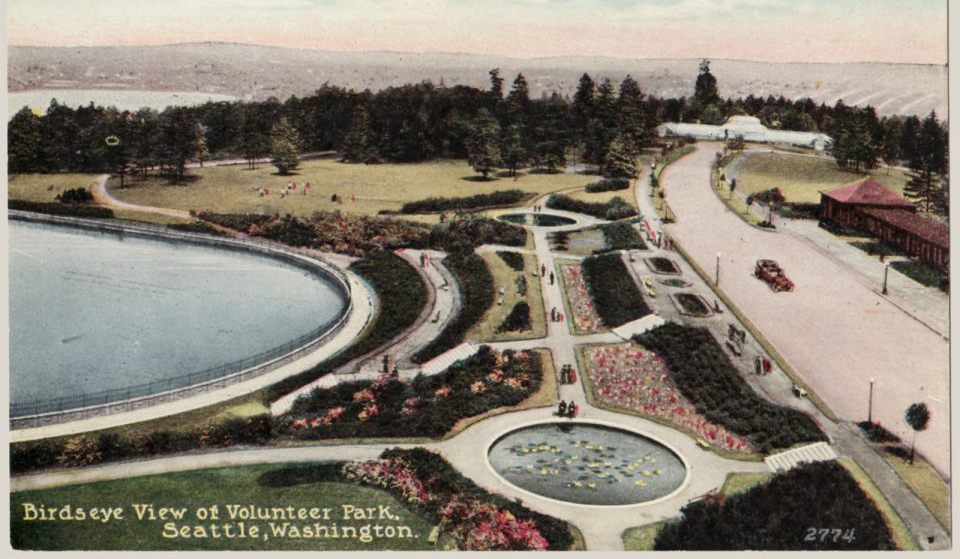

Schwagerl’s plan became the basis for another dreamer. City Engineer George Cotterill (later mayor) organized volunteers to construct and maintain 25 miles of bicycle paths throughout the city. Cotterill’s project was adapted in 1903 and expanded by the famous Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts. Frederick Law Olmsted, founding father of the company and designer of New York’s Central Park, was a disciple of the “City Beautiful” movement, which attached spiritual and democratic values to public amenities. Seattle’s Olmsted plan, never fully realized, was accepted in anticipation of the imminent 1904 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition and the city’s purchase of two large tracts, Woodland and Washington Parks.

The Olmsted plan had one principal goal: locate a park or playground within one half-mile of every Seattle home. This meant that public recreation would manifest itself in field houses, ball fields, tennis courts, and playground equipment. Another realized goal, largely due to the city’s heaving and convoluted topography: vistas and viewpoints everywhere.

The Municipal Plans Commission soon found another dreamer, Virgil R. Bogue (1846-1916). Fresh from designing the Port of Tacoma, Bogue flew high with a design that called for a civic center in the Denny Regrade, an interurban tunnel under Lake Washington linking Seattle and Kirkland, and the purchase of Mercer Island for a park. Voters couldn’t believe what they saw and businesses protested the relocation of the business center to the Regrade, so it was nixed in a 1912 vote.

Seattle parks were off to a running start. While the city grew and nurtured its Olmsted parks over the first 50 years, a young man from St. Louis, Missouri arrived in the Pacific Northwest in the 1950s with his wife, Miriam, and two children. Besides a degree from Ohio State University, Donald N. Sherwood’s background in commercial art suited the Seattle Department of Parks’ need for brochures and recreational programs. When the department’s architect suddenly left, Sherwood found himself thumbing through park maps and responding to inquiries from the public.

When the Parks Superintendent suggested that Sherwood compile sketches of the parks, annotated with historical information, the assignment presented a clean state to research and describing every city park and playground. His next step was to ensure that records were saved, sorted, and made available to the public — and, most importantly, to himself. He became the go-to source regarding data and lore related to Seattle’s vast park system.

Sherwood’s style and historical interests grew exponentially. Following in the footsteps of Seattle’s civic dreamers, he never wavered in digging deeper into the world of our city’s parks and civic recreation. His research appeared to be endless, and most of that work emerged, hand-written, within cryptic notes and references attached to park and playground maps.

One example is “Seattle’s Woodland Park Zoo; subtitled Ancient Origins.” An excerpt gives the flavor:

“Domestication of the Wilderness for lumber and/or agriculture and animal husbandry led to the development of community centers with chiefs . . . [A]s kings accumulated power through wealth, they sought amusements for their leisure time and the capture and containment of wild animals suited their fancy. . . . Rameses II kept herds of giraffes, lions and ostriches. Ptolmey II collected lions, leopards, cheetahs, camels, ostriches, and elephants. . . . King Solomon and King Hyram of Tyre indulged in the trading of exotic animals. . . . Romans . . . added the spectacle of show business – the bloody spectacle of the Roman circus. . . . [I]n the Tower of London the price of admission could be a cat or dog to be fed to the Lions. . . . [T]he first permanent public menagerie opened in London’s Strand – “Pidcock’s Exhibition of Wild Beasts.”. . . The “garden concept” became a model for the Zoological Society of London in 1828. . . . [T]he garden setting for a zoo really caught on: Dublin in 1831; Amsterdam in1838; Stuttgart in 1842 . . . Central Park in 1865; The Bronx in 1899.”

Sherwood’s script continues with the story of Canadian Guy C. Phinney (1852-93), who, after the Seattle fire of 1889, selected a 188-acre tract of woodlands that included a half mile of frontage on Green Lake. To attract visitors to his park (for a fee) he established an “Ostrich Yard” and confined a bear named “Bosco” in a pen. Bosco was a hit, for he would stand up to beg for peanuts. Over the years, Finns herded reindeer in the park who were headed for Alaska; cavalry horses encamped awaiting their embarkation to the Philippines for war; other animals were added after Phinney’s death. Mrs. Phinney sold the park to the city for $100,000.

Sherwood ends his manuscript by sending a fond salute to the staff and volunteers who cared for the animals, especially noting Italian immigrant Frank Vinzenzi, who worked at the zoo for 40 years, the last ten as director, and famous for bringing small animals to visit ill kids at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital. Vinzenzi’s unofficial title was “Gentle Friend of the Animals.”

The colorful Sherwood History Files can be found online at Seattle Municipal Archives; at the Seattle Parks and Recreation Department; and at the Seattle Public Library. They recount the efforts and dreams of early Seattle leaders who were challenged but never defeated by Seattle’s Seven Hills.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Interesting footnote: The Olmsteds did not favor a large central park for Seattle, even though founder Frederick Law Olmsted created such masterpieces as New York’s Central Park and Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Instead they thought our grand views were outward, to the mountains and bodies of water, and so contrived tree-lined boulevards to suddenly open out to these majestic outward views, and linking small parks into a necklace tying together the city. Olmsteads’ plan was only partially completed. And Seattle’s efforts for a large downtown park never got off the ground — unless you count Seattle Center and the new central waterfront park.