My wife, Marguerite, who was CEO of Colin Powell’s youth foundation, America’s Promise Alliance, and who knew Powell better than I did, made the best comment I’ve heard about him and our era: “We’ve lost the last great man of our lifetime.”

I heard a lot of other eloquent commentaries on Powell’s life and character at his funeral last week in D.C. My wife was invited and I was not, but she got me on the list. I was moved, inspired, and amused by what I heard and saw at the memorial service.

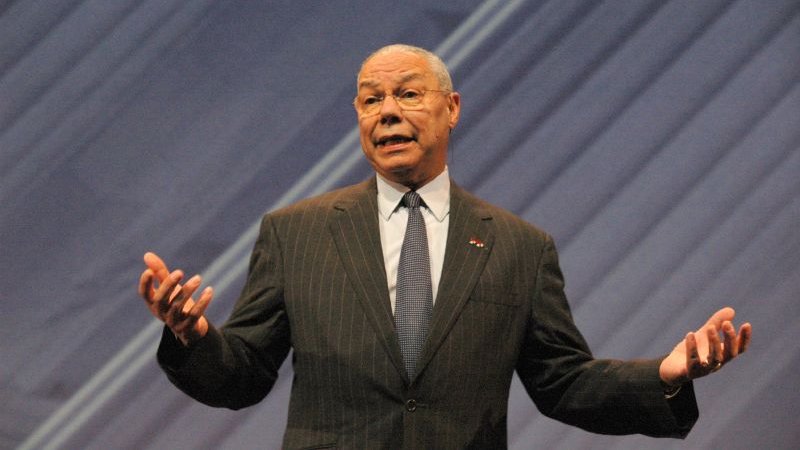

As befits a man of his stature — a distinguished and history-making Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (first Black, youngest ever, and successful planner of the first Gulf War) and first Black Secretary of State who also helped produce a peaceful end to the Cold War — the Washington National Cathedral was filled to its capacity of 4,000, by invitation only.

Attendees included President Biden and two former presidents (George W. Bush and Barack Obama); Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and four former Secretaries (James Baker, Madeleine Albright, Condoleeza Rice, and Hillary Clinton) plus a bevy of other dignitaries including Robert Gates, Gen. Mark Milley, Powell’s family, former colleagues in the military, diplomatic corps, America’s Promise, and just friends.

It was a bipartisan affair of a kind one doesn’t see in America much any more, but it was not “political.” The former presidents didn’t speak. Those who did were family and close friends (his son, Michael Powell, Albright, a Democrat and former sparring partner who became a good friend, and his closest friend and former Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage.) I saw only one sitting Member of Congress, Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-Mich). Former President Donald Trump, who had disparaged Powell within 24 hours of his death, was not invited. No other prominent present-day Republican leaders were there, either.

Powell didn’t formally split from the GOP until after Trump’s Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, but he supported and voted for Democratic presidential candidates beginning with Obama. (He also voted for Jimmy Carter in 1976, but was dismayed by his foreign policy and “hollowing out” of the post-Vietnam military.)

The service was full-on Episcopalian featuring stirring hymns and Scripture readings presided over by leading clergy. Armitage said that Powell “loved the church, loved the liturgy” and was available to talk every morning of the week except Sunday. It was also full-on honor-guard military, with music by the US Army Brass Quintet and private burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

The humor came in eulogies and the music. The brass quintet played not only patriotic and religious songs, but also “Dancing Queen,” made famous by ABBA, identified as one of Powell’s favorite artists; “Three Little Birds” by Jamaican singer-songwriter Bob Marley (Powell’s parents came to the US from Jamaica); and “American Tune” by Paul Simon. Michael Powell told stories about his father’s tinkering obsession — piling up adding machines to take apart and put back together and “fixing” Michael’s perfectly-running 1962 Chevy so that it could only be driven in reverse, which is how Powell delivered it two miles to a fire station as a charity donation.

Armitage recalled being called to Powell’s State Department office to find him on one knee with the Swedish Foreign Minister, who’d given him an ABBA album, and singing the score of the musical “Mama Mia.” Diplomatic officials present were “gob-smacked,” his friend said.

At an Inaugural ball sponsored by Black Entertainment Television honoring Obama in 2009, my wife and I saw Powell on stage singing with Beyonce. A close friend remarked, “Colin is so happy here—he doesn’t have to pretend he’s white.” That surprised me, given that his biographer, Karen DeYoung, quoted family members as saying race was never a conversation topic at home and that Powell, though he strongly supported affirmative action, strove to advance (and succeeded) strictly on merit, not because he was Black. But, DeYoung wrote, it didn’t hurt for him to score high marks in every post he ever held and also be Black.

Growing up in the polyglot Bronx section of New York City and attending mixed-race City College of New York, Powell did not experience racism until he served in Southern Army bases as a young military officer in the late 1950s and early ‘60s. When he was headed to one base driving with his wife Alma, who was pregnant, it was a chore finding “colored” bathrooms she could use. He said he didn’t feel safe until he was north of Baltimore. Yet he was not bitter and did not believe America was irredeemably racist. He evidently thought the country was still a work in progress. He titled his autobiography, My American Journey.

His exemplary career, so far as I can see, had but four flaws: DeYoung reported in her book (Soldier: The Life of Colin Powell) that in early 1969, Powell wrote a memo “in direct refutation” of charges by a US enlisted man that American soldiers routinely abused Vietnamese civilians—shooting some and torturing prisoners. Powell wrote that relations between US soldiers and Vietnamese people “are excellent.”

This was six months before freelance investigative reporter Seymour Hersh published a report on the March 1968 massacre of hundreds of Vietnamese civilians, including pregnant women and children, in the village of MyLai in the territory where then-Lt. Col. Powell was serving. DeYoung reported that, while Powell arrived for his second tour in Vietnam four months after the massacre, it was widely discussed in his unit and “it was unlikely that Powell…was unaware of it,” and he later said that relations between US soldiers and the Vietnamese were “awful.”

Second, Powell himself acknowledged that his February 2003 speech before the United Nations Security Council, asserting (based on bad intelligence) that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction and had ties to Al Qaeda, and his supporting of George W. Bush’s ill-fated invasion of Iraq, was “a blot” on his record.

He had feuded mightily beforehand and after with Bush’s war hawks, Vice President Dick Cheney (who attended the funeral) and Defense Sec. Donald Rumsfeld, over the rush to invade with little international support and the insufficiency of forces to carry out the mission. Powell’s UN speech convinced the public and many other doubters, including Democrats in Congress, that Bush’s case was solid. Clearly, it was not. And the invasion led to chaos in the form of massive looting followed by civil war between Sunnis and Shiites and the rise of ISIS.

The invasion clearly violated the Powell Doctrine, based on the disaster Powell witnessed in Vietnam (and successfully followed in Operation Desert Storm): before using force, have a clearly defined mission that’s in America’s national interest, build popular support for it, then use overwhelming force to accomplish it.

Despite all of that, for years afterward, he defended Bush’s decision to go to war. The explanation seems to be that Powell thought of himself as a soldier who, like Gen. (and then Sec. of State) George C. Marshall during and after World War II, might disagree with the president’s decision but was duty-bound to carry it out. (Marshall opposed Truman’s recognition of the State of Israel, which he believed would lead to war in the Mideast.)

The third flaw was that Powell, who was quick to bond with almost everyone he met and invariably made his superiors into enthusiastic supporters, allowed himself to be outmaneuvered by Cheney and Rumsfeld in the hard-elbowed contest for Bush’s attention. As DeYoung recounts, the two war hawks had frequent one-on-one meetings with Bush. Powell had few.

The explanation could be that Bush simply was intent from the get-go to topple Saddam Hussein—thinking, with Rumsfeld’s and Cheney’s neoconservative staffs, that it would lead to democracy in Iraq and other Mideast autocracies, and that there was no way Powell, the doubter, was ever going to break in. But Powell didn’t insist on frequent meetings until well into Bush’s presidency. Then, for all his pains and service, he was not reappointed in Bush’s second term and that decision was communicated to him not by Bush, but by his White House Chief of Staff, Andrew Card.

The fourth flaw, I thought, was that Powell, regularly named in polls “the most trusted man in America,” did not use his influence to organize fellow “heavyweights”— such as fellow ex-military leaders, diplomats, business leaders, entertainment figures — into a bloc (and then a popular movement ) regularly speaking up to counter growing polarization and incivility in American society and recommending good policy and opposing bad.

Powell knew he was widely admired and had influence long after he left office. He made strategic interventions with well-timed interviews and actions—endorsing Obama in 2008, and speaking out against Trump, for instance—and studiously guarded his brand.

He might have been president, maybe a great one, given his moderate, pragmatic views and world-wide respect. But, in 1996, he announced that he lacked the “passion” to run for political office. (His wife also opposed it, fearing he might be assassinated.)

I was an advocate of such a systematic “heavyweight” organization and intervention and once asked him whether he’d support (or maybe lead) it. He replied, “Aw, you guys in the media wouldn’t pay any attention to us.” I think he was dead wrong and let his cynicism about the media get in the way of action.

But, flaws aside, he was a great man. He rose from humble (though family-strong) beginnings to be a war hero, a strategic thinker, a small-d democrat equally at ease with hot dog vendors and world leaders, a shrewd bureaucrat, a man who knew his own mind and was not afraid to speak it, a gifted leader who invariably was admired by colleagues and subordinates, a significant agent of social change (his America’s Promise Alliance, chaired by his wife after he became Secretary of State, organized national program that successfully lifted the nation’s high school graduation rate), and a genuinely good man. There is no one on the scene at the moment or foreseeable future who is anywhere near his equal.

As his son said in eulogy, “the example of Colin Powell does not call on us to emulate his resume, which is too formidable for mere mortals. It is to emulate his character and example as a human being. We can do that.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Ironic that GW was front and center at the remembrance !!!!

Thank you for sharing all the details of this very moving service. It sounds like the kind of celebration he would have enjoyed.