Former Seattle City Councilmember Nick Licata got introduced to campus demonstrations in 1966 during his freshman year at Bowling Green State University, a conservative school 125 miles from Cleveland. For the young activist-to-be the political awakening began when one of his dorm-mates rushed down the hall, hollering at the top of his lungs: “There’s a crowd heading over to the girls’ dorm. Come on, let’s go!”

Caught up in the melee, Licata followed the mob. The rioters were chanting, “We Want Panties!” The girls’ response was enthusiastic. Dorm windows opened and panties rained down on the throng. The panty raid resulted in one arrest, that of Ashley Brown, a student activist who was merely standing by, along with property destruction that “could run as high as $600.”

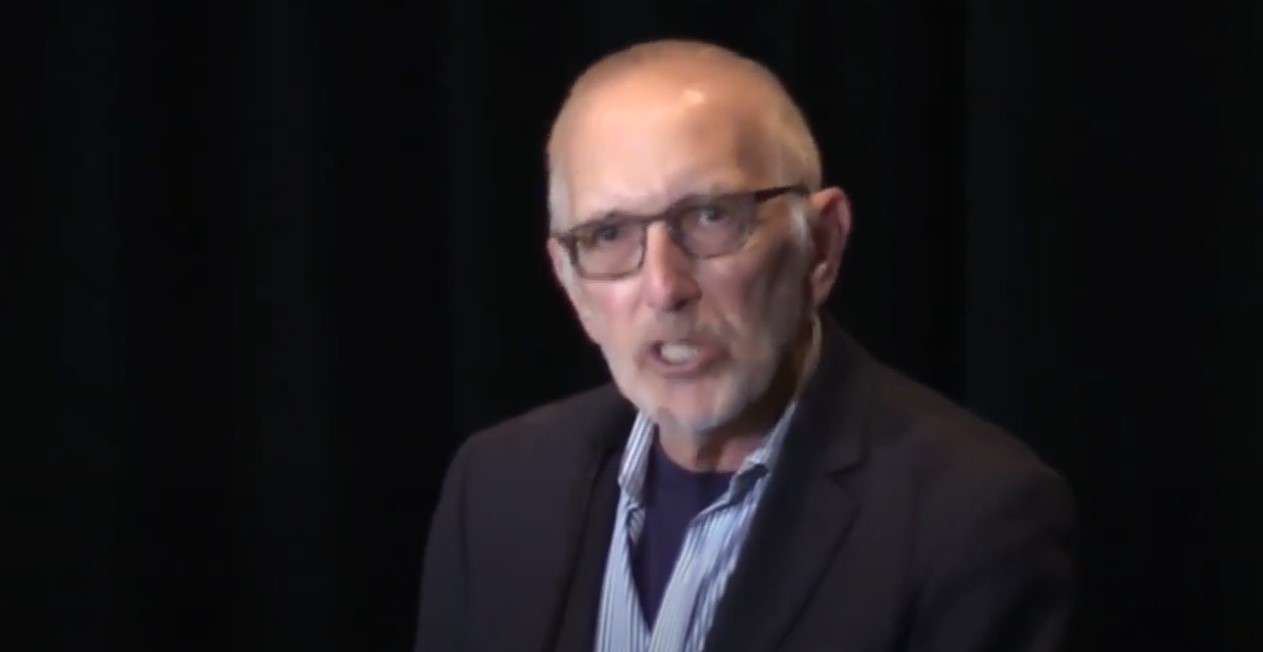

That springtime lark was a less-than-inspiring forerunner to the mounting student activism that lay ahead during Licata’s memorable four years at the institution. Licata uses personal insights and humor to catalog the rise of the student movement in his new book, Student Power, Democracy and Revolution in the Sixties Licata earlier authored Becoming a Student Activist, an award-winning handbook on activism drawing on movements like Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter.

Licata’s newly-published book chronicles how BG’s mostly working-class student body struggled to exert a measure of control over the administration’s outdated in loco parentis regulations. As an example, Licata reports that, when first-year women arrived at the school, they received a handbook of rules governing their behavior — men students did not. The women’s handbook, distributed since 1923 by the Association of Women Students, established inflexible rules of conduct, including appropriate dress (knee-length skirts) and strict curfew hours for all women. The handbook contained two notable restrictions: women could not smoke or kiss in public. (Men were free to smoke.) If caught violating a rule, women could be confined to their dormitory.

Licata discovered his activist voice during sophomore year, supposedly “the year of wise fools.” He’d spent his summer working as a dog catcher. Although he’d always been afraid of dogs, the job paid well and he needed tuition money. His final summertime employment was as a tomato grader at the Heinz ketchup factory, separating green tomatoes from red. For the notoriously color-blind Licata it was no easy task. He had to rely on help from friendly farmer/suppliers.

Late one night during his first year Licata had encountered John Betchik, a fellow student called “Ivan” for his Russian heritage. Like Nick, Ivan had been writing “bad” poetry in a “beatnik” hangout. The two explored the counterculture and became fast friends and roommates. That fall they happened to notice an item in the Bowling Green News that the Ohio Board of Regents was ordering the university administration to adopt a quarter system (rather than semesters) the following year. “No one asked us,” said Ivan, slamming his hand on the paper. Nick agreed they should “do something.” Ivan proposed, “We’ll start a petition.” But how to get word to the students? What they needed was a mimeograph and, in their quest, they ended up at the Crypt, housed at the United Christian Fellowship Center.

Although suffering guilt over entering a Protestant Church, Licata (a practicing Catholic who’d once considered the priesthood) managed to run off a handful of petitions. Standing in the middle of the campus the next day, the two buddies attracted a couple of hundred signatures and, to their surprise, landed a front-page picture in the BG News, the college paper. Licata ruefully notes that “on an earthier note, it made it easier to meet girls.”

In the aftermath, Licata met David George, who was on a mission to convert students into activists. George said they needed to form a campus chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The previous year, SDS had joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in an anti-war march in D.C. That led the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover to describe the organization as “a youth group with an active communist infiltration.” As Licata says, “I had always wanted to see who a communist was and now it seemed I could be one.”

The Bowling Green SDS, described by Licata as a “puny organization” with few paid members, forged an alliance with other campus groups. Together they worked to encourage student questioning authority and also to pursue a social justice agenda, eliminating poverty, war, and discrimination.

After a summer learning to squeegee walls, Licata found himself leading the SDS chapter and, surprisingly, the next year as a candidate for student body president. It was a job he believed would go to one of the handsome, blond fraternity students. But, incredibly, the post-election day headline read: “Licate Sweeps Presidency.” (Licata, along with his family, would later change their surnames back to its original spelling.)

In his senior year, Licata, as student body president, presided over increasing student engagement, including addition of two members of the Black Student Union to the Student Council. The students were pushing to set their own rules and regulations and end discriminatory practices. At times, he says, it felt like playing a chess game with the administration.

While BG students were gaining more control through mainly peaceful protests and demonstrations, the national SDS organization was becoming more authoritarian, splitting into groups such as the Weatherman faction that wanted to declare war on the U. S. government. After attending the national convention, Licata sadly concluded the organization’s leaders had veered off the rails, uncertain whether to mobilize youth or radicalize the working class.

Licata argues that the student power movement, too often packaged along with civil rights and anti-Vietnam War actions, deserves to stand as a separate entity. The movement involved more than just gaining student rights at individual schools. It fostered social justice beyond the campus and shared a cause of gaining political power to change the status quo.

In the book’s concluding chapters, there’s a tendency to get entangled in the sea of lettered organizations and bureaucratic hair splitting. This reader could have used a glossary to accompany the helpful index. The book’s afterward includes the author’s reluctant look at his own FBI file. Licata found no surprises, although he was amused to discover that the anonymous informant suggested he had been elected student body president “due to lack of student interest in voting.”

Licata’s book, published by Cambridge Scholars, is oddly pricey. Amazon earlier listed the hard cover at $99.95, but now it’s “currently unavailable.” The book can also be obtained through cambridgescholars.com for $61.99. Perhaps the book will ultimately go into paperback and become less dear, particularly considering its target audience. That said, Licata’s book is a worthwhile historic document, a snapshot of turbulent times made more personal through tart observations. As he observes (and his subsequent career in Seattle attests): “Being a student is a temporary status, while being a citizen is a lifetime occupation.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Another way that campus activism spread more widely is the tech world: college campuses, young people with modest control of their energies, and many new businesses being cooked up in dorms, as with Facebook and Microsoft. The right also learned a lot about individualism and libertarianism from the 60s, as witness Newt Gingrich. Once you uncork this kind of bottle, the champagne spreads through the room. This is true particularly if, like Seattle, Boston, and the Bay Area, you are basically a college town.

David, can you elaborate on what makes Seattle feel like a college town? As a Harvard graduate, the student presence in Boston and Cambridge was inescapable. But even today living just one block from Seattle University, I find that Seattle has a college presence but is hardly a college town. The UW is certainly a massive institution in its corner of the city, but other industries (tech, port/maritime, life sciences) seem to carry much more weight in the city’s identity than higher ed.