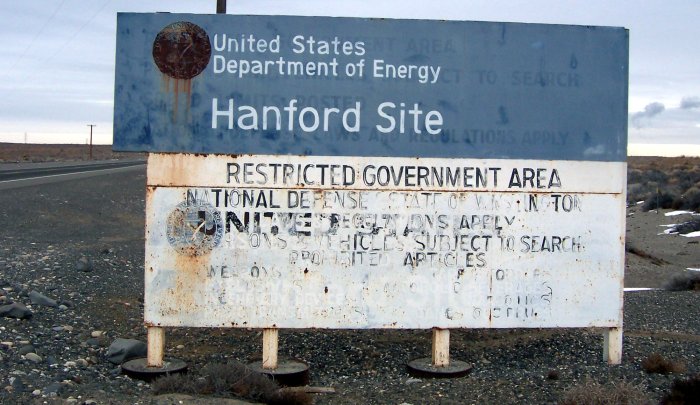

Most folks who have lived in the Northwest very long know of the ongoing contamination and cleanup mess at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Eastern Washington. The site is the repository for tons of radioactive waste and sprawls out over hundreds of miles. There have been countless stories over the years about management (or lack thereof) of the site, and the cleanup, such as it is, has been underfunded for decades.

Continuing danger to the region is very real. And at least one scientist says there’s danger of a Chernobyl-scale meltdown. Now the prestigious Virginia Quarterly Review in its fall issue details the current threats in a deeply-reported article by Lois Parshley, a widely published freelance investigative journalist, and photographer Sean McDermott that ought to scare the bejesus out of you. For example, they report, 57 percent of workers at Hanford have been exposed to hazardous materials, and radioactive material has leaked into the region’s watersheds and into the air for decades.

The article starts off with the story of Abe Garza and a Hanford crew going on a routine inspection in 2015 and emerging with bleeding noses that deepened into neurological afflictions that lead to dementia.

“Garza’s experience is common among Hanford workers; in July 2021, a new state report found that a shocking 57 percent of Hanford workers have reported exposure to hazardous materials. But as dangerous as they are, the toxic vapors Garza’s crew encountered aren’t necessarily the tanks’ worst hazard. It wouldn’t take much for a tank to fuel a massive explosion, one that Tom Carpenter, executive director of the watchdog group Hanford Challenge, says could spread radiation over a staggering area: Washington, Idaho, Oregon, “probably Utah and maybe Canada, depending on the wind direction and speed.” And some of the tanks at Hanford reached the end of their design life during the Vietnam War. As the site’s infrastructure ages, it’s hard to overstate the danger. Carpenter warns that the consequences of a tank fire would be on the order of Fukushima. (Dan Serres, conservation director of Columbia Riverkeeper, points toward Chernobyl.)“

Still, despite the ongoing danger, the cleanup has been chronically underfunded, and “in the face of these rising costs, the [Department of Energy] announced in 2019 that it would redefine what constitutes ‘high-level radioactive waste’ under federal law, which would allow it to leave additional waste in place, rather than transferring it to safer, long-term storage.”

Just as we discovered the poverty of long-neglected infrastructure at the start of the COVID pandemic, Hanford has slipped as a priority because it is largely out of sight and none of the worst nightmarish incidents have taken place yet. Indeed, the article, while not explicitly stating so, suggests that when scary warning signs leak out, they are suppressed, such as in this anecdote:

Although there are fences and warning signs around the nuclear reservation, questions about the extent of Hanford’s health impacts continue. Lonnie Rouse, who worked at Hanford for decades, explained how he would be sent out with a can of spray paint and a dosimeter to find radioactive tumbleweeds, which regularly absorb radiation from waste leaked into soil, and travel widely as part of their lifecycle. “We’d spray them pink to watch and record how far these things went,” he said. Pink tumbleweed kept showing up in Richland. “People started freaking out, so we quit painting them. But that doesn’t mean the radioactivity stopped.”

Warnings about the site have been around for years, but the article says that the risks and danger are escalating as the facilities age. Geologists say the power plant at Hanford — which “stores spent fuel rods in pools similar to the Fukushima reactor” — is at risk of an earthquake two to three times more powerful than it was designed for. An earthquake could set off a nuclear catastrophe on the order of Fukushima.

It’s difficult to plumb the true depths of the hazards at Hanford. John Brodeur, an environmental engineer and geologist who worked at Hanford in the 1990s, wrote that the DOE’s leak-detection method is “not only flawed, but designed to avoid finding leaks.” In 2008, the DOE announced that it had reclassified waste that had leaked or been spilled from Hanford’s tanks. “That was kept a secret,” Carpenter says. “Nobody knew it, not even the state.” From these leaks and spills—and places where waste was intentionally dumped—plumes of hexavalent chromium, as well as cyanide, uranium, strontium-90, technetium-99, and iodine-131, are all now in the groundwater, at risk of being joined by radiation from waste left in the tanks. Whether these plumes reach the river depends on what happens next.

Though the contamination will be around for thousands of years, workers and monitors of the site who have been around for decades and know the scale of the issues and what to look for, are dying off, making it all the more difficult to truly assess and properly deal with the scale of the problems.

As the site’s risks balloon, workers and policy-makers are being forced to confront Hanford on a human scale. People with firsthand knowledge of activities around the site are retiring. Others who tried to hold the government accountable, like Russell Jim, have passed away. President Biden has made environmental issues a focus, but his administration has shepherded through a budget for Hanford for this year that’s $900 million short of what’s needed. The idea that Hanford is a problem has itself become part of the problem. Local reporters have faithfully catalogued Hanford’s accidents and consequences, so no one seems shocked when a new scandal there arises; the fresh angles on abuse of power have run out. But injustice doesn’t seem to be sufficient—broader attention requires some degree of novelty.

A long story, but well worth the time.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.