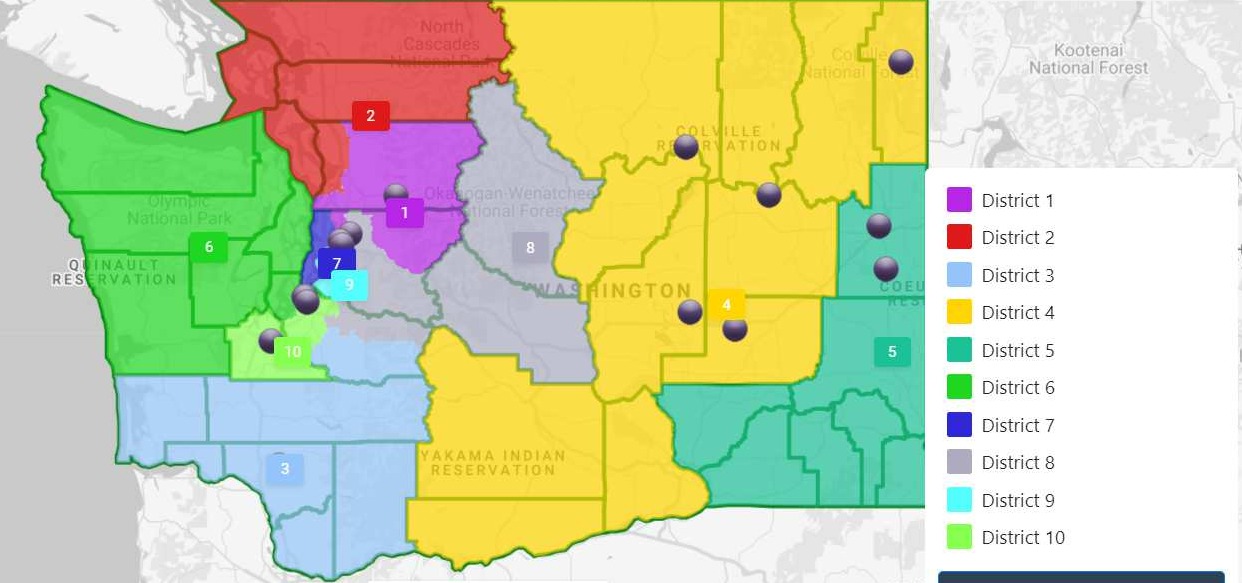

Last week I took a first look at the hardball politics of the initial round of proposed maps from the Washington Redistrict Commission. Since then, a helpful source slipped us a breakdown of which incumbent lawmakers might find themselves shivering in the political cold¹ outside of the friendly confines of their existing districts. It’s an interesting list², full of realpolitik, partisan animus, and the occasional intraparty sacrificial lamb.

But first, a reminder that the nominally bipartisan redistricting process here — a four-member commission appointed by the four caucuses of the Legislature — ultimately will require three votes to approve a final map. This first round of maps is nakedly partisan, so it’s likely that much of what we’re writing about will not actually come to pass. But it’s still interesting to see where — and at whom — the commissioners chose to throw a few brush-back pitches.

We’ll start in Southwest Washington, where both Democratic maps write Rep. Jim Walsh, R-Aberdeen, out of the 19th District, which stretches from Longview to the coast, and into the 24th, which runs up the Olympic Peninsula to Sequim. The existing boundary runs between Aberdeen and Hoquiam. The new 24th pushes into Aberdeen to pick up Walsh’s home.

Commissioner April Sims’ redrawn boundary between the 24th and 19th Districts leaves 19th District Rep. Jim Walsh stranded in the 24th.

Walsh, a pugnacious conservative fond of baiting his progressive adversaries in committee and floor debates, was the first Republican to win in the 19th for decades and proved to be the leading edge of a GOP takeover of one of the last rural Democratic strongholds. The 24th is now that last stronghold, and if the D maps were adopted, Walsh would have to run against one of two Democrats who represent the district if he wanted to stay in the Legislature. And without Walsh in the race, Democrats might have a chance to reclaim a seat in the new 19th.

Over in Clark County, both Democratic maps move the boundary of the 18th District so that Sen. Ann Rivers, R-La Center, would wind up in the 20th District, currently held by Senate Minority Leader John Braun, R-Centralia. Both Braun and Rivers were just re-elected, so this wouldn’t necessarily be an issue until their next Senate race in 2024, but Rivers — who survived both a Democratic challenger and a write-in backed by conservative Republicans in her district last year — can’t be happy about it.

Clark County, which is increasingly influenced by that big progressive Oregon city just across the river, represents an opportunity for Democrats. Accordingly, the map drawn by former Rep. Brady Walkinshaw, representing the Senate Democrats, also moves neighboring Sen. Lynda Wilson, R-Vancouver, from the 17th District into the 18th, which would give Democrats a better chance of seizing the swing 17th in 2024. It also moves one of Wilson’s Republican house seatmates, Rep. Vicki Kraft, and both GOP House incumbents in the 18th, into the safely Democratic 49th. If that stands up, Democrats could have real opportunities to gain ground in the House next year.

The Republican maps also signal ambition to win back recently lost territory. The map proposed by former Rep. Paul Graves, representing the House Republicans, is the most aggressive of the four in terms of displacing incumbents. He would move a whopping 25 Democrats out of their districts³ in his quest to create more districts that are winnable by Republicans.⁴

Among his targets: Sens. Emily Randall, facing a tough reelection battle next year for the formerly Republican 26th District in Kitsap County, and T’wina Nobles, who ousted Republican Steve O’Ban in Pierce County’s 28th District last year. On the House side, his plan would displace some 17 Democrats, including Reps. April Berg, Melanie Morgan, Debra Entemen, My-Linh Thai, Vandana Slatter, and Monica Stonier. All eight lawmakers named in this paragraph are women of color.

Former Sen. Joe Fain, representing the Senate Republicans, also draws Randall out of her district. Fain’s map is more subtle than Graves’ with fewer outright displacements. Interestingly, neither Republican map displaces Sen. Mona Das, D-Kent, who narrowly defeated Fain in South King County’s 47th District in 2018. Both Republicans, however, draw a 47th far less favorable for the incumbent.

Out in Eastern Washington, the map created by Commissioner April Sims, a labor leader representing House Democrats, would displace veteran Sen. Jim Honeyford, R-Sunnyside, and Rep. Jeremie Dufault, R-Selah, from the 15th District into the 14th. Sims redraws the map to create a majority-Hispanic 15th around a united Yakima, which is currently split between the 14th and 15th Districts, both represented entirely by white Republicans.

The division of Yakima, and also of the nearby Yakama Indian Reservation, is widely considered by Democrats to be an example of “cracking,” or dividing a community between districts so it’s effectively disenfranchised. Cracking is one of the classic tactics of gerrymandering.

A few of the displacements are friendly fire, with incumbents sacrificed for a larger political purpose. For example, both Democratic plans write Sen. Liz Lovelett, D-Anacortes, out of a completely redrawn 40th District and into a new 10th, which includes Anacortes, the San Juan Islands, and Whidbey Island. It’s part of an ambitious gambit to create three Democratic districts in northwest Washington, replacing one Democratic district and two swing districts.

Lovelett was crosswise with many in her caucus earlier this year over her Washington STRONG carbon tax proposal, a competitor to the cap-and-trade proposal that ultimately passed the Legislature. She pointedly skipped an appearance by Gov. Jay Inslee in her hometown in the final weeks of the session.

The Democratic maps would set up a faceoff in 2024 between Lovelett and Republican Sen. Mark Muzzall, R-Oak Harbor, who were both re-elected last year. While Lovelett would have three years to make friends and influence people in the new 10th, she might still find herself in a contested primary against a Whidbey Island Democrat with a strong local following.

Traditionally, Washington’s redistricting system has served largely to protect incumbents rather than displace them. The next few weeks will feature extensive bargaining and horse-trading as commissioners work to find a map that at least three of them can live with. It’ll be interesting to see who gets left out in the cold.

Footnotes:

- 1. State law requires a candidate for office to be properly registered to vote within the jurisdiction. So an incumbent drawn into a new district would either have to run there or move into their old district. Both tactics have been used. U.S. Rep. Adam Smith, whose 9th Congressional District was radically redrawn a decade ago, prompting him to move to Bellevue, is the most high-profile example.

2. It’s likely the list has a few omissions or other flaws. With 147 lawmakers, at least a few will likely have moved recently enough for records to be out of date.

3. This number is something of an exaggeration, as some of these displacements will merely inconvenience the incumbents. At least two displacements, Rep. Shelley Kloba, D-Kirkland, and Sen. Bob Hasegawa, D-Seattle, appear in all four proposals. That typically indicates the incumbent has indicated he or she won’t seek reelection.

4. The Republicans have the more difficult task in this process because Washington has far more Democratic-leaning voters than GOP-favoring voters. Accordingly, their maps would aggressively rewrite the landscape to try and overcome that structural disadvantage.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Regarding the first footnote: state law requiring people live in the Districts they represent only applies to state and local bodies.

Members of Congress only have to live in the same state, and are not required to live in the district they represent. Congressman Adam Smith did not have to move when the 9th Congressional District lines changed in 2011, but he did. Perhaps because the schools are better than those in his previous home. Pramila Jayapal did not live in the 7th Congressional District when she ran in 2016, something supporters of her challengers tried unsuccessfully use against her. She did, however move into the 7th from the 9th.

These shenanigans are why authors wrote this sentence into the Charter Amendment for Seattle’s City Council redistricting process:

“In drawing the plan, neither the Commission nor the districting master shall consider the residence of any person.” Article IV, Section 2, Subdivision D(3).

Such a provision might be difficult to enforce with 149 legislative incumbents (plus numerous potential candidates), but over time it should help reduce the game playing. Even better would be a wholly non-partisan process.