Angela Merkel, the most powerful woman in the world, is about to end her 16 years as German chancellor with 80% approval ratings, Europe’s most vibrant economy and a record of uniting domestic political forces and the other 26 fractious nations of the European Union.

No wonder German voters have been all over the political map this year in deciding who should succeed her after Sunday’s parliamentary elections.

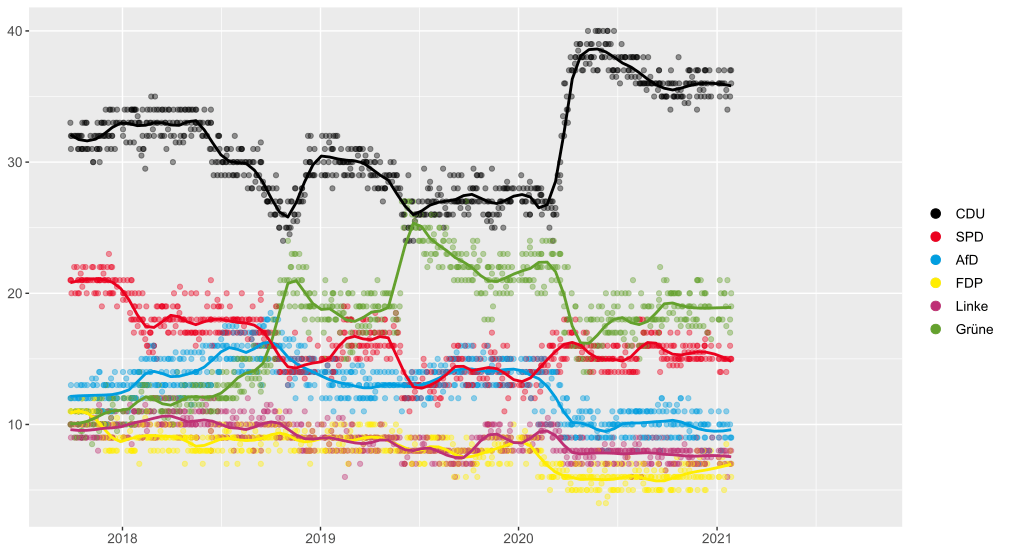

The latest aggregate of Germany’s multitudinous polls scatters voter support so widely among the six parties in contention that the leader whose party wins the most seats in the Bundestag will have to woo two others into a three-party governing coalition.

That effort proved unwieldy and ultimately unsuccessful after a similarly split outcome in 2017. Merkel’s right-of-center Christian Democratic Union and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union, negotiated for two months with the Greens and the pro-business Free Democrats. When talks collapsed, the CDU-CSU formed a “Grand Coalition” with the Social Democrats that has been relatively stable and collaborative under Merkel’s leadership. That won’t happen again. Neither leader of the two mainstream parties is seen to have the desire or the skills to recreate that alliance of strange bedfellows that governed Germany for 12 of Merkel’s 16 years as chancellor.

The post-election negotiations are expected to take weeks, if not months, to deliver a new leadership. Merkel will probably have to continue as acting chancellor for most of the rest of this year and possibly into 2022. While she is widely respected and would win again handily if she wanted another term, German voters grow impatient when the squabbling to form a coalition drags on long after the election.

Merkel endorsed her conservative party’s candidate, Armin Laschet, who emerged the winner of a bruising inter-bloc battle with the CSU in April to run as the “continuity candidate” to carry forward Merkel’s agenda. That made Laschet the frontrunner, until catastrophic flooding blamed on climate change ravaged Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia, where he is governor.

A bright young force in the Greens party burst on the scene in May in the form of 40-year-old Annalena Baerbock, a London School of Economics grad, human rights lawyer and champion for climate action. She leapt in the polls to rival Laschet, until conservative media circulated gossip and rumors of plagiarism in her academic background.

Now, mere days before Germans will cast their ballots, Finance Minister Olaf Scholz of the Social Democrats is leading the race by 4 percentage points at 26% — what passes for an impressive advantage to emerge as chancellor in the next government. Laschet’s CDU/CSU bloc follows with 22%, the Greens at 16%, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the Free Democrats with 11% each and The Left, a successor to the former East German Communists with 6%.

The coalition-building math gets complicated and colorful. German media have long assigned colors to represent the parties: Black for CDU-CSU, Red for the Social Democrats, Green for the Greens, Yellow for the Free Democrats, Blue for the AfD and Pink for Die Linke. The five rivals to the AfD have vowed to exclude them from government.

German voters cast two ballots in federal elections, one for an individual candidate in their local parliamentary district race and the other for a political party. The chancellor is not directly elected. The party with the most Bundestag seats gets first crack at cobbling together a majority government.

If the Social Democrats carry their lead through the Sunday vote, Scholz would likely invite the Greens and Free Democrats to haggle over which party gets what Cabinet appointments. That “Traffic Light Coalition” could founder on the Free Democrats’ opposition to tax increases as proposed by Scholz and the Greens.

Another possible triumvirate, if Laschet and the conservatives eke out a few more seats than currently forecast, would be a “Jamaica Coalition,” so named for the black, yellow and green colors of the Caribbean country’s flag representing the CDU-CSU, the Free Democrats and the Greens.

Which governing alliance prevails will come down to a battle over the priorities of tax relief (in a country where high earners pay 45% in income tax alone) or taxing the rich and spending more to avert climate change. The Greens and the Free Democrats are 20 years apart on the goals for reaching climate neutrality, respectively by 2030 and 2050.

Germany’s foreign policy is unlikely to change much, whatever the outcome. Berlin’s relations with Washington remain troubled, despite the departure of Donald Trump from the White House. European allies fear America’s political division and instability that brought thousands of insurrectionists to the Capitol on Jan. 6 continue to threaten democracy and reliable diplomacy.

Germans and French have recoiled lately from President Joe Biden’s dubious moves in withdrawing U.S. forces from Afghanistan and his fait accompli in cutting a deal to sell nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, which cut a previous contract with a French builder of conventional subs worth tens of billions.

German voters’ indecisiveness on which color spectrum would best serve them is also an indication that no drastic change from the status quo can be expected. The choice boils down to which of the two parties that has been in government for most of the past 20 years should lead for the next four in partnership with Free Democrats and the Greens.

Laschet or Scholz? A governor or a former big-city mayor? Two men in their 60s who have been in politics for most of their lives.

British historian Timothy Garton Ash commented in The Guardian newspaper last week that Scholz would be more likely than Laschet to make the European Union work better for the long-suffering economies of southern Europe but either stalwart would prevent the eurozone from collapsing — a fear in some EU countries.

There are few dire forecasts in Germany or elsewhere in Europe of the consequences if one major party or the other wins the chancellery. There is concern, with the prospect of a flood of Afghan refugees heading to Germany after the Taliban takeover, that the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany could gain more seats in the Bundestag. But as they are shut out from the coalition talks, their power would not be much enhanced.

Polls in Germany, unlike those in the United States, tend to be reliable and German voters are anything but volatile.

As the New York Times summed up the excitement level in a headline on the most consequential German vote in a generation: It’s Election Season in Germany. No Charisma, Please!

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.