Early examples of Northwest history are found in Native rock art, cedar carving, utensils, and fabric. British Captain George Vancouver, who visited our shores and bays in the 1790s, spent hours describing everything within view and incidents beyond his vision. In 1841, Lt. Charles Wilkes, USN, kept detailed logs of our shorelines and mountain ranges.

After Euro-American settlement, a number of diligent observers published descriptions of the Pacific Northwest. Here’s a small sampling of those efforts: Clarence Bagley on Seattle history; Stewart Holbrook on our great rivers and forests; Parker McAllister’s illustrations; troubadour Woody Guthrie on the Columbia River and its mighty dams; Roger Sale’s Seattle: Past to Present.”

I list below four influential Washington historians. These men (and there were many women who told our story, such as Sophie Frye Bass, Lucile McDonald, Emma Smith DeVoe, and Betty McDonald) brought our region to wider attention.

Vernon Louis Parrington. Born in 1871, Parrington came out of Kansas and was educated at the College of Emporia and Harvard. He tried a short teaching stint in Kansas, and then was hired by the University of Oklahoma (Norman) to teach British literature. He also coached the football team to a winning record, played baseball for the school, and edited the campus newspaper. Because he smoked and was perceived as an elite “Easterner” in a conservative environment, he was fired. Moving to the University of Washington in Seattle, he found an academic niche where his burgeoning political radicalism was appreciated.

Parrington also found time to raise a family, tend a bountiful garden, and begin research on what would become one of the most influential books in American history: the three-volume Main Currents in American Thought. He saw a country dominated by greed and large industry. To his and others’ surprise, his trilogy (partially completed) won the 1928 Pulitzer Prize for History — quite a feat for an unknown teacher of English in the remote Pacific Northwest.

After his sudden recognition, he and his wife Julia took a 1929 vacation to Gloucestershire, England, in the Cotswold Hills, where he passed away from a heart attack. Besides Main Currents he left two other books on the Connecticut Wits and Sinclair Lewis.

Edmond S. Meany. Born in Saginaw, Michigan, Meany headed west and entered the University of Washington. Graduating in 1885 as class valedictorian with a Master of Science degree, he stayed on to take a Master of Letters. He next tried his hand at politics, serving two terms in the Washington state Legislature. The University became his home where he became the dean of local historians and a civic booster.

In 1908, Meany proposed a great local event to advertise the natural beauty and economic opportunities of the Pacific Northwest. This project grew into the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (A-Y-P), Seattle’s first “world’s fair.” It was a resounding success, and the exposition helped expand and beautify the present UW campus, which had been located in downtown Seattle.

Meany’s name adorns a Mountaineers Ski Hut in the Cascade Mountain range, another shelter on the summit of Second Boroughs Mountain, and a Seattle Middle School.

Murray Morgan. Tacoma was Morgan’s birthplace and the site of his affection for the Pacific Northwest. After graduating from Stadium High School, he attended the University of Washington, where he edited the UW Daily. After receiving a Master’s Degree in communications from Columbia University he embarked on a journalist’s career, working for the Hoquiam Daily Washingtonian, Time magazine, the New York Herald Tribune, CBS, a reviewing theater for the Seattle Argus.

With his wife and partner Rosa, Murray spent hours in local museums imbibing details about Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. Those efforts were manifest in his many books, such as Bridge to Russia, a history of the Aleutian Islands; Century 21: The Story of the Seattle World’s Fair, 1962; Confederate Raider in the North Pacific: The Saga of the C.S.S. Shenandoah, 1864-1865; Puget’s Sound,” and his most successful publication, Skid Road: An Informal Portrait of Seattle.

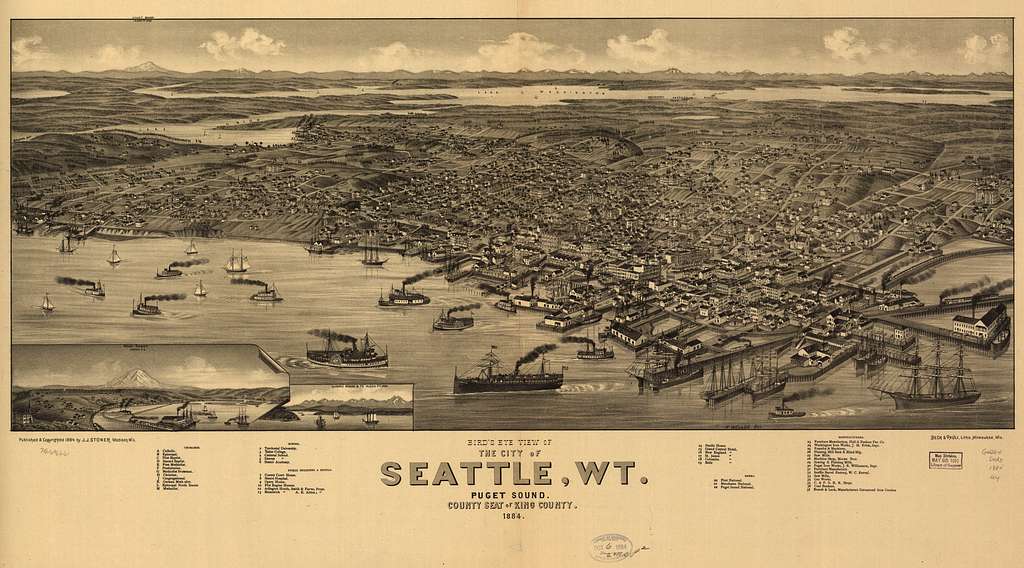

Skid Road took a close look at sometimes-seedy characters from Seattle’s early days: “Doc” Maynard, John Considine, Hiram Gill, Dave Beck. Morgan’s title helped establish the term “Skid Road” throughout the world. Despite skewed use of the competing term “Skid Row,” Murray had it right – the original log roads, sometimes coated with bear grease, where horses, oxen and early steam engines hauled and skiddedharvested trees to sawmills. In the case of Seattle, Henry Yesler’s mill (the town’s first employer) pulled logs over Seattle’s seven hills, including Yesler Way (First Hill), to the waterfront. A male-dominated community grew up around the mill, abetted by saloons, bordellos and cheap eateries – later sometimes referred to as “Skid Row,” describing local residents as “on the skids.”

Murray Morgan died in 2000, leaving behind a rich trove of historical anecdotes. Besides his narratives, in 1997 the City of Tacoma named its 11th Street Bridge (where where Morgan had been a young tender in the 1940s) The Murray Morgan Bridge.

Samuel Hill. In the 1850s young Sam and his family emigrated from Deep River, North Carolina to the Midwest, escaping the coming American Civil War. They were a Quaker family and did not believe in violence. Sam graduated from Haverford College and Harvard University. Returning to Minneapolis to practice law, he won a succession of lawsuits against the Great Northern Railway, which unsurprisingly attracted the attention of James J. Hill, the railway’s general manager.

James Hill hired Sam to run his legal department. Young Sam fell in love with and married his boss’ daughter, Mary. Combining the two Hill families resulted in Sam’s consequent rise to prominence. Around 1900, Sam undertook his own businesses, began travelling internationally, including aboard the new Trans-Siberian Railway, and in 1902 took control of the Seattle Gas and Electric Company. The Seattle project caused him to move to the Pacific Northwest on a more permanent basis.

However, Mary did not find the Pacific Northwest interesting, and after the couple split, she moved back to Minneapolis to live a more social life. Sam remained in the West, planning and constructing iconic projects. Sam helped establish the Washington State Good Roads Association (by the early 1900s the first cars began to arrive in the Pacific Northwest).

Although Sam did not write history, he was a co-founder of the Washington State Historical Society and worked hand-in-glove with Edmond Meany on most of his projects. He was a local historian in the sense that virtually everything he accomplished was a confirmation and celebration of our region’s past.

His efforts also led to constructing the Columbia River Gorge highway, Portland to The Dalles; establishing the first chair in highway engineering at the University of Washington; building the Peace Arch on the U.S.-Canada border; erecting Stonehenge replica above the Columbia River, a monument to the dead of World War I (and eventually the site of Sam’s crypt after he died in 1931); and designing and building Maryhill, first as his residence overlooking a planned Quaker community in the Columbia Gorge, and later converted to a museum with the help of Portland-area friends.

Who are your favorite Northwest historians? List in the comments section.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

An exciting subject! For Seattle-centric historians, Thomas Prosch and Charles Bagley are obvious favorites. Angie Burt Bowden (“Early Schools of Washington Territory”), a Walla Walla pioneer, and Phoebe Goodell Judson (“A Pioneer’s Search for and Ideal Home”), pioneer of Cowlitz and Nooksack Rivers, provide rare, sympathetic perspectives on the plight of Native Americans. Thanks for the opportunity. Would like to see further installments on this subject.

Ruth Kirk, who died only in 2018, was one of the most prolific of Northwest writers on Northwest themes, from history to ethnography to archeology. She wrote clearly and directly, and above all accurately, avoiding the myth-fostering and sentimentality which devalues mant=y local chronicles.

Robert Ficken. He wrote a trio (Washington Territory, Washington State and Washington: A centennial history”) of modern classics of Washington State history. These are unique books because they do not depend on secondary analysis based on other histories, but rather original research. I’m actually kind of surprised he didn’t make the original list. His recent tragic and untimely death leaves a lot of work undone by him

Cecelia Carpenter (and others). Obviously, the above list is of white men. Even my above suggestion is a white man. It is worth adding to the list the names of tribal and non-white, non-male historians. Carpenter in particular is an example of a historian who conducted deep original research and provided a history that probably no one else could from insider her community.

Would be nice to include a woman historian or two on your list. The late Cassandra Tate comes to mind. Her recent story, “Unsettled Ground” on the Whitman “massacre” (a racist term, I fear) makes fascinating reading, setting the historic record straight.

There’s also James Swan who writes about the early years in this neck of the woods.

It would be an unfortunate oversight to exclude Walt Crowley, founder and developer of the invaluable historylink.org, which continues to provide well-researched, well-written essays on almost every aspect of Washington State history, and remains an evolving encyclopedia of Washington, available instantly to anyone with a computer.

I salute the nominees sent by readers. Besides appreciating their professional work and styles, I knew Murray Morgan very well and my paternal grandparents were close friends of the Parringtons. Of course some of our best historians are women and I will attempt to close that gap in a future Post Alley story.