The fur trade, which two centuries ago opened up the Northwest to international trade and white settlement, traces to fur companies in France, England, Russia, and New York. Less well known is the connection with Hawaii, which has surprisingly many links to our region.

The Missouri Valley spawned our continent’s obsession with catching and trading fur-bearing animals for profit. St. Louis grew into the emporium for this activity, which became western America’s first gilded business. Collecting, transporting, and selling wild animal parts became the major employment of the Far West for 50 years, approximately 1800 to 1850.

The commodities, or legal tender of this trade, consisted of beaver, mink, fox, bison, bear, deer, and small forest animals. The trade later expanded to buffalo tongues, bear tallow, bones, feathers, animal teeth and horns. To expedite this activity white-owned companies were formed to procure furs from Natives. Regularly employed hunters and trappers were hired at fixed wages and irregular deals were made with “free” hunters and trappers.

Annual western rendezvous or established trading posts offered opportunities to meet, consort, gamble, engage with Native women, drink and trade these products. Among the popular ultimate destinations of the furs and peltries were Montreal, New York City, Paris, and London. Major fur trade companies in the West were Hudson’s Bay (established, 1670); the Missouri Fur Company (1808); the Russian-American Company (1799); the Northwest Company (known as “Nor’westers” (1780s); and New Yorker John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company (1810).

Native influences in the trade were essential and significant. Natives trapped beaver and hunted bison. Often they resented the presence of white visitors in their country, as with the resistance of the Blackfeet in today’s Montana. Inter-marriage between white hunters/traders and Native women often eased the tensions.

Hawaii enters this picture in the 1780s, when Euro-American sea explorers and traders used the Hawaiian Island chain as a wintering port. Sandwich Islanders, known as Kanakas, came aboard ships as crew and joined the fur trade. When American Captain Robert Gray visited Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island, he met a young man named Atoo, son of a Hawaiian chief.

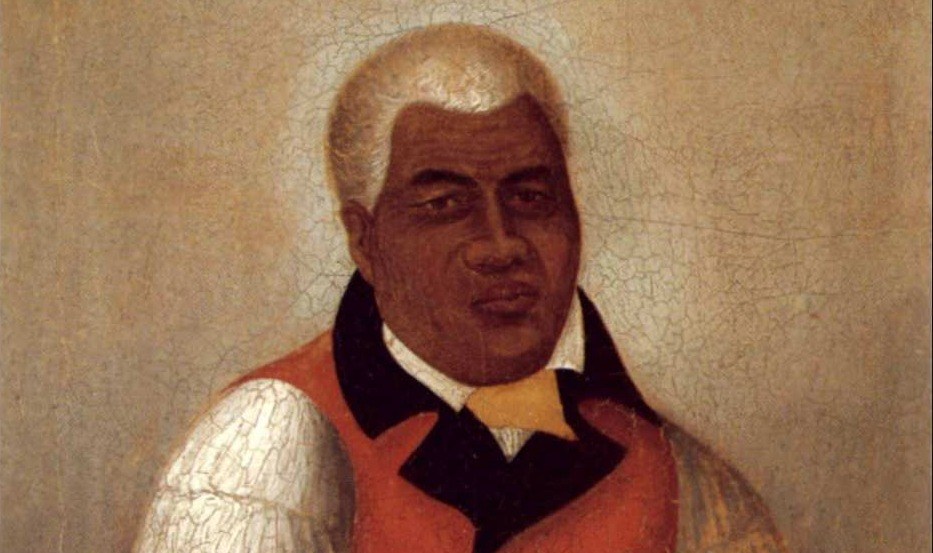

King Kamehameha I (1795-1819), conqueror of the larger Hawaiian Islands, found himself the center of attention during this period. Euro-American traders sought him out, paid the required fees and demonstrated proper obeisance to his office and court. In return, the king provided basic needs for these visitors, including sturdy men – Kanakas – as crew aboard ships.

During the fur trade an intermixing of Caucasians, Indians, and Polynesians became obvious. “Boss” positions were usually held by Scots, French Canadians, and Iroquois Indians. As a result of marriage and “country” partnerships, racial blends in other positions included French-Indian, Scots-Indian, Kanaka-Indian, French-Kanaka, Iroquois-Indian, and a few Black-Indian residents.

The Astor party in 1811, eager to participate in the lucrative western fur trade, established the port town of Astoria at the Columbia River mouth. When Astor’s ship “Tonquin” arrived that year, it carried 24 Kanakas. Two years later, 13 more Islanders arrived at this wet, cloudy outpost. By 1814, many of these newcomers wanted to return home. Working in a dark rain forest alongside a huge roaring river in no way matched their native balmy, sandy beaches.

Life in Astoria was occasionally dangerous, and Nor’wester diaries described the Kanakas as willing to “do everything.” The Hawaiians lived apart from the main community, observing their traditional death and marriage rituals and celebrating Hawaiian New Year in October.

The British Hudson Bay operation at Fort Vancouver, 20 miles upriver from Astoria, also included a Kanaka contingent. By the 1840s, an Owyhee church was established at Fort Vancouver with “Kanaka William” as pastor. At both Astoria (briefly held by the Americans) and Fort Vancouver (the British), besides living in their separate communities, Kanakas planted their own fenced gardens and raised corn, potato eyes, turnips, cucumbers, and radishes. Several Islanders married Native women, establishing mixed-race families.

To the north, Washington’s Nisqually Prairie and Cowlitz River country also hired Kanaka workers. The Puget Sound Agricultural Company in 1841 employed 616 people. Islanders worked at nearby farms and ranches – 3,000 acres of open country accommodating over 200 cows, 50 horses and assorted hogs, chickens and goats.

East of the Cascade Mountains, Nor’wester David Thompson, the first Euro-American person to travel and map the entire Columbia River, took “Cox” (or”Coxe”) as his assistant. Thompson noted in his journal that Cox was a “Sandwich Islander,” and was an expert with paddle and canoe.

The sea otter trade, which originally drew American and other traders, fell off due to over-harvesting and the introduction of rival materials made from silk, cotton and other fabrics. The beaver trade had almost disappeared, and those animals became a protected species. Disease, alcohol, war, and bald racial prejudice decimated the Natives. As the trade declined, fur traders and trappers eventually retired or returned to the Old Country. Most Kanakas found transportation back to their ocean beaches, while others remained with their Native families on the American mainland.

After the fur trade had drifted into history, these “mixed” families became part of the American fabric. Kanaka settlements can be found today on the Canadian Gulf Islands, especially Salt Spring and Russell. Other remnants are on the banks of the Columbia River (e.g. Kanaka Creek, Stevenson, Washington) and upcountry near Danner, Oregon close to the Owyhee (i.e. “Hawaii”) River.

Other surprising traces remain. Beachcombers in the Gulf Islands have come upon a Lu’au feast on a wet, rocky beach, and have occasionally been invited to share a Kulua Pig on a spit with a helping of Poi (taro root) topped by Hasupia (coconut pudding), washed down by a local beer.

Kalua pig isn’t on a spit. It’s kalua because it’s cooked underground.