Seattle’s Broadway on Capitol Hill is a mostly two-lane arterial street that has been bruised, modified, chopped up, and re-born many times. It runs a 1.6-mile course from First Hill’s Yesler Way northward to Capitol Hill’s East Roy Street. Other Seattle “Broadways” pop up here and there, but are not part of the First Hill-Capitol Hill route.

Broadway may not be a wide street, but it provides a broad path into Seattle’s history of rapid growth.

Emerging from ancient hillsides – once the province of great Douglas Fir forests and wild thickets of ground cover – the future Broadway is the birthright of Vashon Glaciation. The Pleistocene ice sheets, sometimes 2-3-miles thick, pressed the earth’s crust. After the ice melted, beginning approximately 16,000 years ago, knobs of earth we identify as Seattle’s “seven hills” moved upward. These natural prominences were surrounded by puddles, rivers, waterfalls, lakes and other bodies of water. Seattle’s paramount examples of the latter are Lake Washington to the east and Puget Sound on the west.

Our region’s earliest visitors from Asia carved primitive trails that later evolved into the roads, alleys and highways of the 21st century. Population growth and a robust economy (especially after the 1897-1898 Klondike Gold Rush) encouraged Seattleites to explore outlying neighborhoods. Adventuresome citizens moved toward Lake Union, while a new class of entrepreneurs and political leaders moved uphill, behind the rough village in Pioneer Square.

Local sources sometimes identify Colonel Granville Haller and his wife Henrietta as one of the first families to build a grand mansion on First Hill. Their three-story home with a tower, called “Castlemount,” was built on the northeast corner of James Street and Minor Avenue. Other notable families followed: Morgan and Emily Carkeek (Morgan was a contractor/builder), five other Denny families, and members of the Stacy, Lowman (Lowman and Hanford building in Pioneer Square), Burke (law), Collins (homesteaded the Duwamish Valley), Stimson (real estate and wood products), Blethen (Seattle Times), and many more.

Once these prominent residences became established, they were joined by social, religious, educational, and athletic amenities. For example, the Seattle Tennis Club opened its doors in 1890 as the Olympic Tennis Club. The club’s courts were built adjacent to the Martin Van Buren and Elizabeth Stacy residence at the northeast corner of Madison Street, now the Men’s University Club.

In 1901, Trinity Episcopal Church was built on 8th Avenue below the crest of First Hill. A few years later St. James Cathedral arose between 8th and 9th Avenues. In 1922, at 8th and Seneca, the Fourth Church of Christ Scientist was constructed (it’s now Town Hall Seattle), completing Seattle’s hillside “church row.”

These edifices were complemented by Summit School in 1905; the elegant Mediterranean-style Hotel Sorrento with the city’s first rooftop restaurant; and Spokane architect Kirtland Cutter’s Stimson-Green Mansion, built in 1901. Despite the affluent activity and architectural efforts of an emerging, forward-looking generation, it all came to an end for First Hill. Other neighborhoods – The Highlands, Madison Park, Washington Park, Capitol Hill, etc. – began to thrive at the end of new streetcar lines. First Hill became second fiddle, until it reappeared as “Pill Hill,” the city’s primary center of hospitals and medical clinics.

The year 1908 was transformative, as radical changes occurred along Broadway and its spurs, alleys, sidewalks, trolley lines, and businesses. The establishment of Swedish Hospital signaled the first step in altering the neighborhood. It involved a bold move by a Swedish immigrant, Dr. Nils August Johanson, and a flock of Scandinavian supporters. In 1917, Dr. Tate Mason and others started a group medical practice, calling it Virginia Mason after Dr. Tate’s daughter. In 1915, Mother Cabrini took over an old hotel as a hospital, followed by Columbia/Cabrini Hospital, Providence Hospital (founded by Mother Joseph and the Sisters of Providence), Harborview Hospital, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and an array of doctors and dentists offices. Harborview’s towers (the original site of the castle-like King County Courthouse on “Profanity Hill”) were completed in 1931.

Seattle medical personnel often chose living quarters on or near Pill Hill. Before many nearby small hotels and apartments were razed due to new city regulations related to earthquake and fire threats, nurses, technicians, and others found single-occupancy residences, often with shared bathrooms, near their work stations. The 1908 Fenimore Hotel on Broadway at E. Jefferson served that purpose, and will do so again after a remodel and expansion.

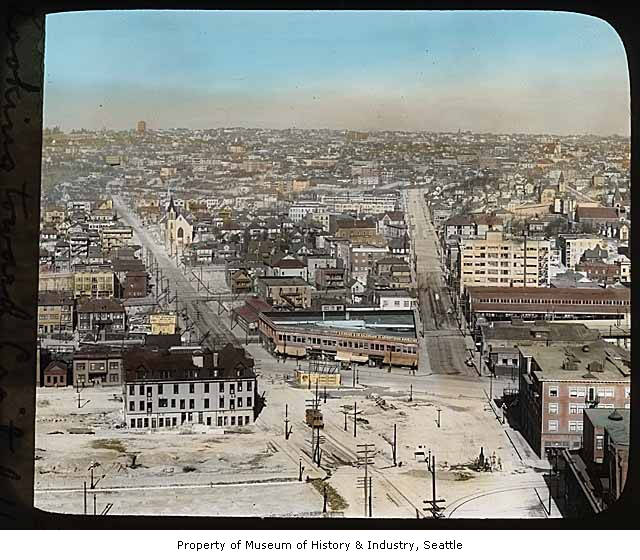

Soon cable cars arrived to serve this new population. Cable cars rode up James and Madison Streets to Broadway, then headed east, as Paul Dorpat writes (2001), “through a patchwork of forests and stump fields – the latter surmounted by real estate signs promoting convenience of cleared lots placed close to the tracks. A fourth electric line ran north and south along Broadway connecting the three hills north to south, Capitol, First, and Beacon – topographically three sisters in the same ice-age ridge.”

One of those busy streetcar lines ran north and south along Broadway, between Yesler Way to within a block or two of Capitol Hill’s Volunteer Park and Lake View Cemetery. This line also opened up an opportunity for developer James A. Moore, who introduced generous home tracts across Capitol Hill, especially “Millionaire’s Row” on 14th Avenue, with Volunteer Park’s old water tower at the north end. Moore’s neighborhood legacy of noble solid homes can still be appreciated.

Today, Broadway is rated by the city as a “Major Transit Street” between Pine and Roy streets, and a “Minor Transit Street” from Yesler Way to Pine Street. Three King County Metro routes serve this area, notably Route 49 on Broadway, which connects Capitol Hill to downtown and the University District. These transportation opportunities helped create one of the Seattle’s most livable and dense urban villages.

At the southern end of the Broadway spine is another notable project, Yesler Terrace, dating to 1941. The idea for a public housing project can be traced to the efforts of one remarkable person: Jesse Epstein. Epstein, born in Russia and raised in Great Falls, Montana, was asked to help solve a problem of all the World War II job-seekers who migrated to the region and overwhelmed the housing.

In the 1940s young Epstein wrote the original Seattle ordinance to set up a housing authority. He was then chosen as Executive Director of the new body’s Board of Commissioners. The Yesler project’s core was at the far southern end of Broadway, just off 8th Avenue. The undertaking was coordinated by J. Lister Holmes, an eminent Seattle architect, with terraced landscaping by Butler Sturtevant. Yesler Terrace was built with federal funds and was the first such project in the nation to be racially integrated.

Yesler Terrace is currently undergoing a mixed-income makeover at the hands of Vulcan Construction (Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s company), in conjunction with the Broadway street-end, revisions to Yesler Way, and a new streetcar route. The “million-dollar views” of Elliott Bay and the snow-capped Olympic Mountains have been preserved.

Next: the story of modern Capitol Hill and the new Broadway.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.