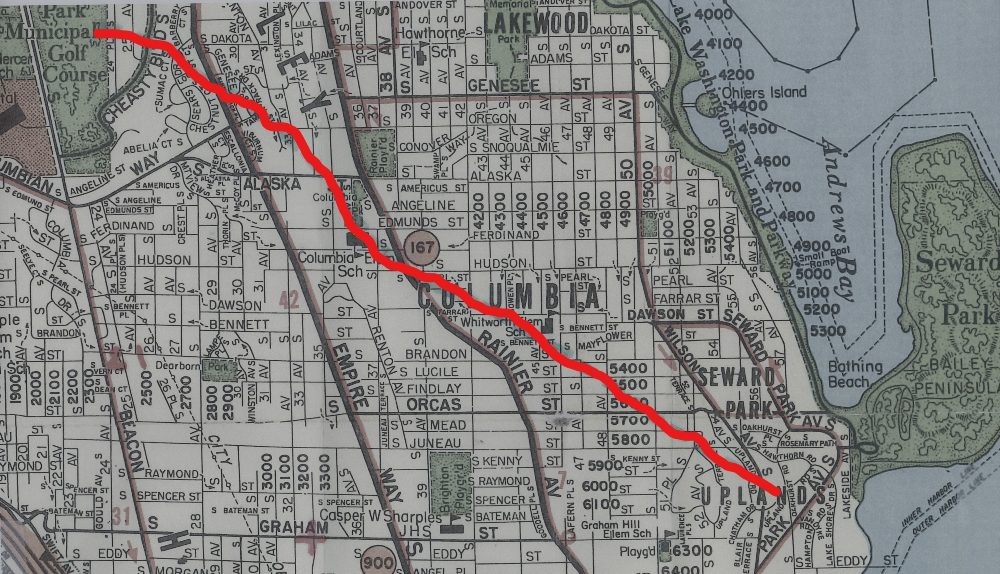

An ancient Native trail, almost invisible today, once passed through south Seattle from Jefferson Park golf course to Lake Washington at Seward Park. Two friends and I revisited the old route and re-encountered the world it once traversed. It can still be found in the midst of a modern city. Come along for the walk.

Edwin Richardson, who originally mapped this trail, received a contract from the United States Government Land Office on May 25, 1861 to survey the township making up most of south Seattle. On a beautiful May morning anthropologists Nile Thompson and his wife, Carolyn Marr, parked their car at Seward Park, and I drove all of us to where S. 24th St. makes a jog at the edge of the Jefferson Park golf course. That’s where the old native trail began.

A township is defined as a square of land six miles on a side encompassing 36 square miles, each of which is called a section. These sections are numbered boustrophedon, “as the ox plows,” beginning in the township’s northeast corner with section 1, going west to section 6, dropping down to 7 and heading back east where the process is repeated — back and forth as an ox would plow a field, until reaching the township’s southeastern corner at section 36. Section 16, where the trail left a wagon road, is near the township’s center.

The process of creating American townships began in 1785, in eastern Ohio, where to pay off its war debts the federal government began surveying and selling public land to private citizens, many of whom were veterans of the Revolutionary War. Settlement invariably preceded surveys as pioneers sought the best ground before being required to pay for it. Prior to sale, surveyed ground needed to be cleared of any previous inhabitants, and this inevitably led to warfare as native groups resisted being driven off their land onto reservations or to unsurveyed land further west.

The Oregon Donation Land Law passed by Congress in 1850 set this pattern in motion in the Pacific Northwest. This most generous of surveys gave 160 acres to a single man, 320 acres to a couple (half of a section), completely free if they would settle on and improve it. This was done to tip the demographic balance in the Northwest in favor of Americans rather than British subjects, and it gained the U.S. Puget Sound, the mouth of the Columbia River and a huge swath of territory reaching from the Pacific Ocean to the crest of the Rocky Mountains. For the predominantly white settlers the survey was a golden gift. For native people it was the engine of genocide. In the Seattle area, war broke out in 1855 and ended in 1858 when native groups were defeated and forced onto reservations.

A foot and horse trail Indians had used to travel from a village at Puget Sound called Dzee dzuh LAH litch (at today’s Pioneer Square on the Seattle waterfront) over Beacon Hill to another village at Renton, Tu hu DEE du, “where it [the river] goes in,” (the source of the name Duwamish). The trail crosses section 16. Early settlers made this a wagon road that surveyor Richardson used in his work in what at the time was regarded as virgin forest.

The branch trail we explored left that wagon road for the lake about three blocks south of where s. 24th St. makes its right-angled jog. Down a steep eastern cliff the jog becomes S. Andover Street. The cliff is the headwall of an old landslide that tumbled to the western edge of S. Martin Luther King Jr. Way. Our nosing around a private drive at the brink of the cliff caused local alarm. An anxious hidden voice called out, “Who are you and what do you want?”

“Wandering,” I replied as we retreated down the street, only to hear the same question from a neighbor standing resolutely in her garden. My response, “We are in search of an old Indian trail from here down to Lake Washington,” charmed our interrogator, Tana Christianson. On the first day she moved into her house some 40 years ago, she hosted a citizen gathering determined to prevent the widening of S. Cheasty Boulevard down slope from her house and preserve what today is the Cheasty Greenspace. We enjoyed a wonderful conversation and I even sold a copy of my book, Chief Seattle And The Town That Took His Name (Sasquatch Books, 2017). Off to a good start.

On August of 1851 Richardson began working the east-west line between sections 9 and 16 at what is now busy Hanford Street. He described the land as rolling, with first-rate soil in low places and second-rate above — that is, rich humus in watered spaces and sandier, dryer soil above. Fir, cedar, maple, alder, ash, crabapple, and hemlock overshadowed smaller trees and shrubs: vine maple, willow, salmonberry, salal and ferns.

We looped down 24th to Cheasty and made the descent north to what eventually became S. Bradford St. Tall, slim maples anchored the slope, their translucent leaves intensely green. Salmonberry is still plentiful with trailing blackberry vines, not the bland Himalayan variety. And here and there in the tangled jungle weathered stumps recall the forest Richason saw. Robins, sparrows, and chickadees scolded.

Because it is not advisable to wander this greenspace into the unfenced back yards of homeowners, we followed a circuitous course crossing the ghost trail several times that brought us down to a community garden at the corner of Bradford and Morse Avenue S., made lush by springs still issuing from the slope. Even this early, the kale had already gone to seed. Richardson too encountered cold, dashing streams and pellucid springs. He also noted prairies, “openings,” and “deadenings” marked where the Duwamish regularly set fires, thinning the forest so sunlight could penetrate and nourish an understory of berry and fern (good forage for grazers).

At least 15 settlers had already established pre-emption claims of 160 acres in or around section 16, and Richardson noted their “Improvements”–a few vegetable patches and cabins planted in the openings. The claims of the earliest settlers: Luther Collins, Jacob Mapel, and Henry Van Asselt show in his records as do claims by Ira Woodin (founder of Woodinville) Mary Anne Boyer (Seattle’s first madam), and John Pike and Seymour Wetmore whose surnames became street names.

We emerged from steep forest to attractive older homes planted on gentler grades and we bottomed out at S. Andover Street among monotonous gray apartments fronting noisy MLK Way S. and its rumbling Sound Transit trains. Over a century and a half of often violent change had been telescoped into less than an hour’s walk.

I had discovered the trail recently while enlarging Richardson’s township map for a hearing and noticed faint dashes marking the “Trail from Lake Duwamish [Washington] to Seattle” while surveying the line between sections 22 and 23. Surveyor Richardson had walked the trail’s length and traced its route on his map. We followed it as best as we could through the tangle of S. Dakota St., 30th Avenue S., S. Adams Street, Renton Avenue S. and S. Oregon St., to Rainier Avenue S., pausing to eat our lunches at Adams Park. The Rainier Valley Electric Railroad bought 40 acres here in 1890, built a sawmill, and sold lots to a community it boomed as Columbia City. People followed. Rainier Avenue replaced the railroad and Columbia City has become a destination with bakeries, a host of restaurants, a new bookstore.

The trail route crosses S. Alaska St. to follow the treeline of Columbia Park to the Angeline Apartments on Angeline St., both named after Sah bo LEE tsah, the daughter of Cheif Seattle, whom pioneers dubbed Princess Angeline. They made of her a bathetic mascot in the way San Franciscans did their “Emperor Norton.”

Next, the trail route meets Rainier Avenue at an acute angle at the Flying Lion Brewery and the Taco City Taqueria, staying with it until leaving at the same angle and heading southeast at S. Lucille St. Spring water from the steep slope fed two creeks that, now undergrounded, flanked our route following the trail as it led to a gentle saddle, a divide that sends one stream, Wetmore Slough, north to what is now the Genesee Park and Playfield, and the other stream, Dunlap Slough, which is named after another pioneer. Then it heads south to Beer Sheva Park near Rainier Beach. Where the slough met the lake was TLOOL tlahs sahs. “Little Island,” renamed Pritchard’s Island, that marked the site of the winter village where Angeline was said to have been born around 1810.

Remarkably, Richardson’s notes inform us that most of the trees encountered along the sections lines he surveyed were around a foot or less in diameter. His job required that he identify, blaze, and measure the diameters of trees encountered along the lines and where they intersected in order to allow future surveyors to locate section corners in his grid. From his accompanying notes, we can estimate the number of trees in a section — about 600 — and that the forest was a matrix of a few large trees (the largest in section 16 a 40 inch-diameter cedar) and many smaller ones spaced far enough apart so that large numbers of deer and elk could flourish on the herbage.

Native people achieved this useful balance by setting local fires every 2 to 5 years, eliminating deadwood, harmful boring insects and disease, and preventing catastrophic fires. Yet there were enough healthy trees to make Seattle and her sister mill towns wealthy. Examinations of at least 200 other township surveys in the Puget Sound region enable us to estimate that 60 percent of the Puget lowland was like this, neither wilderness nor virginal forest but a vast garden maintained by thousands of years of premeditated upkeep.

The trail crossed Orcas Street near its intersection with S. 51st St. and passed between the rocky ridge of the Bailey Peninsula (today’s Seward Park) and a notable hillock rising 325 feet above the lake shore. The old trail disappeared from Richardson’s map within a thousand feet of the shore, near where S. Hawthorne St. meets Wilson Ave. S.

The trail’s end may have evaporated, but it ended in a burst of mythology. Before Lake Washington was lowered in 1916, the Bailey Peninsula was an island at high water, but was betimes joined to the shore by an isthmus: CHKAH lahp sub, “upper neck”. This made it a head-shaped peninsula whose northern point was SKUH bahskt, “noses” or “nostrils.” Who the head belonged to we do not know: perhaps a DZUG wah, a lethal sucking monster that inhaled victims with its big nose, or it may have referred to SEE sohb sheed, the mythical hero of the XAHT chu ahabsh (the X sounded like the ch in the Scottish word Loch, “lake”), the Lake People, who beheaded a sucking monster and ended his reign of terror.

On the lake shore north of the peninsula is S ai YAH hos, a horn-headed earthquake monster that lived in the landslide scar at Colman Park. South is a place called Xah XAH oltch, “sacred containers.” These would appear to have been boxes that held bones and were lashed to trees as at a cemetery further north on Foster Island in Union Bay. If so, this place may have been the cemetery belonging to Angeline’s birth village. A supernatural monster also haunted the shore near here. Despite these forbidding associations, the foot of the trail was a busy place for travellers.

Ending our bracing 3.3 mile expedition around noon, I awaited the drive back to my car seated on a shaded bench. A beautiful woman cycling by nodded and asked, “How’s it going?” Very well, thank you.

For those heading west, the trail’s lovely lakeshore beginning beckoned upslope to a tangy saltwater world. To those heading west, its high portals at the lake shore prefigured steep hills, steeper stoney mountains and the stark, heroic steppe country beyond. For us, whether on gorgeous days or in dripping rain following the route of the old trail represents a splendid urban treasure where the threads of past times winding along its length enable us to see what is no longer there and contemplate deep change. Following the route, our legs will burn with the same effort climbing or descending.

We can still smell resinous fir, the spearmint of maples, the erotic exhalations of the lake marsh. We can still feel the cool, damp air, the same warmth of the sun, and taste sweet salmonberries, tart blackberries, and purple salal. The trail makes time a permeable membrane. This surprising pleasure gives us glimpses of our city’s earlier and ancient world marked by lights and shadows amid a modern, cosmopolitan city. We should make this route part of our evolving cityscape. It could become a trail between times past, present, and future.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for sharing this history! I hope this will this be in a book soon!

We should definitely make this route a part of our evolving cityscape!

Thanks for the tour, nice to learn of our shared past, even if it also reminds us of wrongs done to the first people. We shouldn’t forget.

Evocative piece. I especially appreciated the line that included the phrase “neither wilderness nor virginal forest but a vast garden.” It served to remind me of something that should never be forgotten.

Well done David Buerge.

Loved the story about your quest for the ancient trail, David. Best of all, you’ve given us a memorable quote: “The trail makes time a permeable membrane.” Couldn’t have been better said.

Not exactly the same, but eerily similar: When I was a kid I lived by Sunset Hill Park, a block from the bluff. Below was Ballard Beach, soon to become Shilshole Marina. To the north was Golden Gardens. Parents would warn us: Don’t play over the bluff! Of course we did. There was a network of trails: The Fox Trail, The Rabbit Trail, The Ballard Beach Trail. The neighborhood kids all knew their names, although we didn’t know (or care) where the names came from. They were all unmarked. Several decades later, and only a few years ago, I stopped by the park to take in the view of Puget Sound and the Olympics. A group of local kids came by and scaled the cyclone fence protecting the bluff. “Let’s take the Fox Trail” one kid said. Oral tradition.

There is no better explanation of survey systems in the US than the middle of this piece. Who’d have thought–right here in the city!