Last Wednesday, Seattle’s best secret, an outsider-art masterpiece of stone, glass, and mortar, the most magical and astonishing “visionary landscape” north of Los Angeles’s Watts Towers, fell to the city’s development juggernaut and the hazards of family legacies. As I watched, the best part of West Seattle’s gem, the Walker Rock Garden, was reduced to rubble. Most of what remains appears to lie in the bulldozer’s path as well.

It might hurt less if the rock garden perished in a grand dust-up of protests, lawsuits, and impassioned newspaper columns. But because it lay largely hidden from public view on an unpretentious side street, its smashing was heard only by a few neighbors. This account is a small attempt to break the silence and record a history that may otherwise be lost. Call it an exposé, a tell-all, a tribute or a requiem—it is also a confession. I was one in a succession who tried but ultimately failed to save this Seattle treasure.

The Walker Rock garden was the fine madness of a truck driver-turned-Boeing rigger named Milton Walker, played out around the modest bungalow where he and his wife and constant collaborator, Florence Walker, lived for nearly 50 years. They moved there from a Hoovertown shanty, a classic Seattle tale of upward mobility. In the late 1930s, their late daughter Sandy told me, “Dad got a job building stone steps at [nearby] Camp Long. At first, he did it just the way they wanted. Then he did it the way he wanted. When the boss asked him, ‘Did you do this?’ he thought, ‘Oh oh, I’m in trouble now.’ Then the boss gave him a $10 raise.’” A stone artist was born.

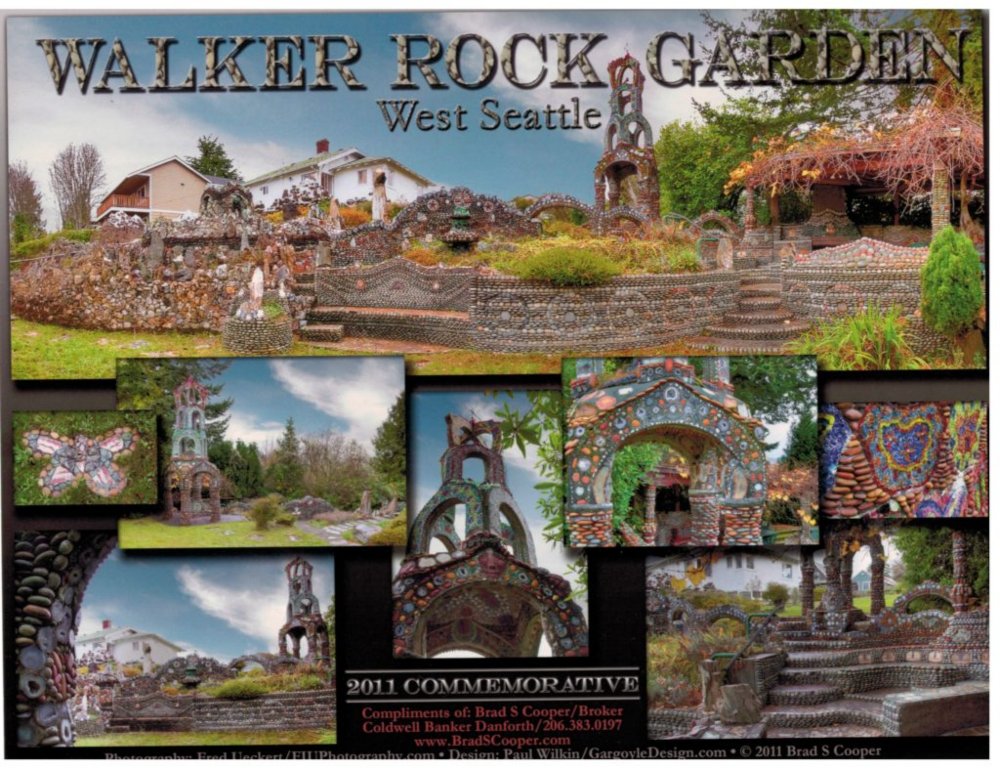

Around 1959, idled by a strike at the Lazy B, Milton began laying stones around the brick barbecue chimney out back, and never stopped. Sinuous pathways and intricate walls, terraces, archways, turrets, grottoes, tunnels, and fountains twined their way across the hillside. In their Dodge Dart, he and Florence scoured four states for material; a roadside rock-shop owner in Oregon offered to sell his 10-ton stock of agates for $150 or $225 (family recollections varied). The Gingko Petrified Forest in Eastern Washington provided another rich lode, back before the state banned collecting there.

The result is a mosaic landscape of river rock, lava rock, agates, thunder eggs, petrified wood, quartz, beach glass, and whatever else caught their eyes. The Walkers’ vision was at once exuberant and serene; as Post Alley’s own David Brewster noted when I showed him the rock garden in 2014, this was outsider art without a dark side. Unlike the usual whirligig collections, junkyard biblical spectacles, and other ramshackle “strange sites” scattered across America, the Walker Garden was the expression of a joyful marriage, not eccentric solitude. And unlike them, it was built to last.

Florence cultivated a more traditional garden, the pride of the West Seattle garden tour, her flowers complimenting the glitter of the agates and glass shards while a velvety moss lawn set off their hard polish. Sandy recalled seeing dad pounce with his pocket knife to uproot any grass that dared intrude.

Untaught, Milton composed so inventively in stone as to recall the Parc Guëll, Casa Milá, and other Barcelona masterpieces of the visionary architect Antonio Gaudí. He’d never heard of Gaudí, but I suspect Gaudí would have embraced Walker as a compatriot—and saluted his artistry and fearless vigor, which Gaudí needed a platoon of Catalan craftsmen to match.

Like Sam (or Simon) Rodia, the immigrant laborer who created the Watts Towers, Milton Walker was a wiry little guy; at Boeing he crawled out into airplane wings to string wires where no one else could fit. Nevertheless, at the age of 70, with no help save Florence’s, he raised an ornate and massive 18-foot tower (sometimes mislabeled “the gazebo”) of cement, stone, glass, and rebar celebrating the U.S. bicentennial. Their grandson Ned Bernath, then about four years old, still marvels at the feat: “He hoisted a horseshoe [one of the arches forming the tower’s top] on his shoulder and climbed right up the ladder. I remember thinking, granddad is the strongest man on earth!” It took me and a strapping young neighbor to lug the remains of one of those arches across the street.

Walker’s garden was hardly the first of its type. “Rocking up,” as he called it, is a folk tradition from Italy to America and beyond; he reportedly took inspiration from the Petersen Rock Garden near Redmond, Oregon. But his craft and imagination surpassed the other rock-uppers, and his whimsy and good humor ran through the rock like a secret code.

For those who looked closely, he embedded cryptic mosaic images—a pinup model, a profile of Charles de Gaulle—and cheery messages: “Happy Birthday, America” in the Bicentennial Tower, “We Wish You Well” above one pond, “You Are Welcome” below the fountain, inlaid like everything else in glorious rock, with colored lights to illuminate its jets of water. Milton would wander incognito at parties and open houses, soaking up the oohs and ahs.

He laid up his trowels in 1979, and Alzheimer’s disease took him in 1984. Toward the end he would ask Florence, “Who made that?”

Friends and Family

Volunteers stepped in to help preserve and safeguard the rock garden. In 1988 the recently deceased jewelry artist Nancy Worden and sculptor/landscape artist Robert “Buffalo” McGillvray uncorporated the nonprofit Friends of the Walker Rock Garden. For 12 years, they and fellow Friends held open houses, pulled weeds, made repairs, and raised funds to buy the property and secure its future. They got advice from a group working to save the creation of another self-taught garden maestro—Kubota Gardens, now one of Seattle’s most beloved parks.

“Our plan was to make it perfect and give it to the city,” says Buffalo, who did the site work while Nancy led the organizing and outreach. “Greg Nickels [then a county councilmember, later mayor] came frequently and offered to help.” They wanted to save it all but devised a compromise that would give the family more money. The plan was to carve off about a quarter of the property for a new, bigger, view house and either donate the rest—including Milton’s finest work—to the city or put it in a secure trust. The existing modest house would be razed, together with a sprawling range of snowcapped mini-mountains right behind it, sculpted with volcanic rock and cement and threaded with roads, tunnels and bridges, representing the Cascade passes he’d crossed daily during a stint as a truck driver. It would be a sad loss, but this section was the least characteristic and most fragile part of the garden, and it’s cavitated badly since.

All went well for several years, Buffalo recounts: Florence and her son George supported the effort, and the Friends raised three-quarters of the agreed purchase price. Then George and Florence died, and her two remaining children, heirs to the garden, grew more suspicious.

Milton’s and Florence’s other son (since deceased) had moved home and, says Buffalo, roiled the dealings: “He saw big bucks from it.” Sandy, their only daughter, was “ambivalent” about letting go of the property, according to both Buffalo and Sandy’s son, Ned Bernath, recall. “I think they always felt that people from the outside were going to get it and make a killing from it,” says Buffalo. That suspicion was piqued when “a busload of architects from Europe” arrived and raved over the garden’s glories.

According to Buffalo and Nancy, the second generation also resented their father for “neglecting” them while he built his masterpiece, complicating their feelings toward it. The deal broke down. The Friends dissolved and gave the funds they’d raised to other 501-C3 nonprofits.

Sold and unsold

As the new millennium progressed, the Walkers’ last surviving son passed away. Their daughter Sandy, her son Ned, and her niece Lita formed a family trust to sell the property. In February 2011 they listed “the famous Walker Rock Garden” at $392,000 with the heading, “Attention, garden enthusiasts, rock hounds or art collectors….”

A developer named Dan Duffus promptly stepped up and signed a purchase contract, then assigned it to another developer, Jim Barger. The Walker’s real estate agent told me in 2014 that it was nevertheless Duffus who dealt with the family, assuring them he would preserve the rock garden. Ned recalls that one or another developer presented a plan showing the existing house and a new second small house in front of the Bicentennial Tower. An elevated, fenced pathway ran between the houses from the sidewalk to a platform where the public could view the rock garden but not enter the yards.

Ned says he and “Cousin Lita” were delighted at this plan. But, says Ned, “Mom found out about that developer’s reputation and refused to go through.” (Duffus pioneered, among other maneuvers, the use of a loophole in city code to pack houses onto tiny phantom “lots,” incensing neighbors in West Seattle, Wallingford, Queen Anne, Montlake and Tangletown.) “Lita and I were pushing her to sell, but she put her foot down.”

“I wasn’t involved with it,” Duffus told me when I reached him in Scottsdale, where he now lives. “I assigned the contract to Jim Barger. He handled everything.” Barger did not respond to calls and email requesting comment.

Sandy kept her foot down, though it cost her money. Barger’s company, Greenstream Investments, sued to enforce the contract. “We reached a legal settlement,” Duffus told me, right after he said he wasn’t involved.

Three years later, in 2014, Sandy put the house and garden on the market again. This time she attached a covenant, drafted with the help of the Southwest Seattle Historical Society, intended to protect Milton’s and Florence’s magical legacy. For 20 years, the house and rock garden could not be altered or removed, and the two lots would have to be kept together as one parcel.

And that’s where I fell into the picture.

Stonestruck

I first saw the rock garden in the late 1980s or early ’90s, after Milton died and before Florence did. I noticed a listing on a local paper’s calendar page: the annual Mother’s Day open house of something called the Walker Rock Garden. I arrived toward the end of the afternoon as other visitors were leaving. The day was cloudy, so the agate paths and geode-laced walls did not gleam as they would in sunshine. But I had them to myself, and I was transfixed and transported.

Afterward I stopped in the house to thank the hosts and express my delight, and wound up chatting with the family, lined up on the couch—Florence, very old but with a youthful twinkle in her eye, her son, and perhaps granddaughter Lita, who would have been a young girl then.

In the spring of 2014, two events occurred whose coincidence seemed fortuitous: the Walker Rock Garden came on the market, and I received a windfall that gave me the cash to buy it (and a tax break if I invested in other real estate). Because it was a windfall, I wanted to do something meaningful, not just gainful, with the money—and here that something was.

Soon I had a purchase contract (the covenant seemed to scare off other buyers) and six weeks for a feasibility review. Sandy and Ned came over from Eastern Washington, where they lived, with a boxful of rock-garden clippings and mementos. Lita came down from the north, where she’d moved, and they shared their memories of Milton and Florence and the marvel they created.

Over the next month I tried to lure over everyone I could think of who might have the expertise or be in a position to help preserve the rock garden. Among those who came to see the rock garden: the Seattle Parks Department’s property and acquisitions director, the city Landmarks Preservation Board’s coordinator, Historic Seattle’s program director, the Southwest Seattle Historical Society’s executive director, the founder and chief technical expert at Artech, representatives of the Seattle Arts Commission and King County’s 4Culture arts agency, and ex-city councilmember (and West Seattleite) Tom Rasmussen. Most had never seen the garden; many had never heard of it.

I hired geotechnical and structural engineers for walk-through consultations; both were so charmed by the rockwork they waived their fees. The problems they identified were serious, however: it might cost $150,000 (in 2014) to replace the leaning retaining wall holding up the whole steep site, or $80k to shore it up with pipes and pilings, plus $30k for the necessary permits, surveys and studies. And that was before you got to conserving the actual rockwork.

Caring for the rock garden would be a lifetime project, I realized—if it were even possible for one person. I didn’t want to own it; I wanted to see it saved. As the closing approached, I came to the same conclusion that, unbeknownst to me, the Friends of the Walker Rock Garden had 20 years earlier: to survive, it belonged in public hands, open to the public.

The way to get it there, as the Friends knew and I belatedly realized, was to separate the house from the garden. Renting, selling, or living in the house would recoup or at least help cover the expense. I could spend a couple years, I thought (perhaps wishfully), seeking aid and protected status and shoring up the site as best as I could, then donate it to the agency most able and willing to preserve it—perhaps the Parks Department, whose property director expressed initial interest, or the historical society, which had restored other historic structures.

But the covenant attached to the sale stood in the way. I proposed to revise it to let the share of the property occupied by the house be legally separated, while strengthening the language protecting the entire rock garden (including the crumbling mountains that the Friends plan would have eliminated). I also proposed to extend the term of that protection from 20 to 25 years.

The transfer scheme might never work, and I might be stuck with a life’s project. But it seemed the best shot for saving the garden.Her son Ned and the family’s real estate agent agreed, but Sandy smelled a rat. She was naturally suspicious after the 2011 sale debacle. And, says Ned, she was still ambivalent about letting go. “She was so hot and cold—she was ready to sell, then didn’t want to.” Furthermore, “her dementia was probably more advanced than we knew at the time.” She rejected the revisions and took the rock garden off the market.

Unraveling

Over the next few years, Sandy’s condition worsened, and she finally passed away; Ned and Lita became sole trustees of the rock garden. He drove over from Ritzville regularly—sometimes twice a week in summer—to battle the blackberries and other weeds digging incessantly into the more vulnerable parts of the rockwork. He’d tried to delegate those duties to a caretaker living nearly rent-free in the house, but they didn’t get done.

I stayed in touch, and offered to help if they were interested in pursuing any of avenues I’d explored. No thanks, said Lita in 2016; she would move into the house, manage the rock garden herself, and make it a venue for weddings, birthday parties and other events.

Good luck with that, I thought. I sent her and Ned a list of all the people and organizations I’d shown the garden to, their contact information, and what I’d gleaned from them. I told Lita I’d like to write some articles to raise public interest and support for the garden. She asked me to hold off, saying she and her family weren’t ready and didn’t want strangers traipsing around the rockwork. Let me know when you’re ready, I said.

After hearing nothing more I decided, in spring 2017, to go ahead anyway. I pitched Crosscut and the Seattle Times’ Pacific Northwest magazine, which I’d been writing features for, proposing one on the need to safeguard Seattle’s forgotten treasure before it was too late. Neither was interested. After so many dead ends, I was burning out.

Meanwhile, Ned Bernath had much more reason to feel burned out. He’d continued driving over from Ritzville every week or two and laboring heroically on the rock garden. Lita sometimes weeded too. “I remember she came down once and said, ‘This is a lot of work,’” he recalls.

Over the next four years I passed by the rock garden periodically, making sure that it was still standing and that no MUP (master use permit) board, announcing redevelopment, had gone up. The last time was earlier this spring. Nothing had changed—visibly. But no MUP was required for simple homebuilding on what is, in legal terms, an ordinary residential lot.

I didn’t know that Lita had offered to buy out Ned’s half-share in the property, and the transfer closed in May 2017. “I gave her a really good friends-and-family deal,” says Ned—$200,000, probably less than half what his share would be worth now. “She told me she was going to live there,” he adds, sadly but without rancor. “I hoped it would stay in the family and stay intact.”

Lita did not respond to calls or email; I haven’t spoken with her in about five years. She continued renting the house rather than moving in. Last September she and her husband, Ken Gill, sold the lower lot, containing the tower and the finest rockwork, to an Auburn-based developer, Stas Repin, for a recorded $375,000. “They called us and offered to sell,” Repin told me, adding that Ken handled the deal. It came with no preservation strings attached.

Ned says that Lita called him last year to tell him she was dividing the lots and invited him to come see the rock garden while it lasted. He couldn’t bear to go.

Excavation

I didn’t get world until last Tuesday, returning from a hike near Mount Rainier, when a friend forwarded a posting in that day’s West Seattle Blog reporting that “redevelopment has begun on the site that holds part of the Walker Rock Garden.” I arrived there early the next morning. The Bicentennial Tower was already down but only half-broken; its river-rock legs and weather-vane crown were lost, but its central portion was mostly intact. A large excavator was tearing up the ground around it and the agate- and geode-embedded walls, arches, terraces, and arches behind it.

I flagged down the excavator operator and begged to save what was left of the tower and anything else I could from destruction. He said I’d have to talk to his boss and that “the guy across the street wants the tower.” I dashed across the street and rang the bell. The guy who answered, a young Boeing employee named John Osborne, said he did indeed ask for the tower, but was told the company would charge him $2,000 to move it.

When the foreman arrived I pled the case again, trying to explain how important the rock garden was to a neighborhood I didn’t live in. He was actually sympathetic, as were the crewmen; all shook their heads at the devastation they were wreaking and said it was a shame. The excavator operator had saved a couple of Milton’s signature stone-encrusted butterfly pavers for himself. But a job’s a job.

Couldn’t you just lift the tower and carry it across the street? I asked. The big excavator was too heavy to cross the street and curb, but a smaller one sat to the side. The foreman told the operator to try. Splayed out like a pietà of rock and rebar, the tower was half-lifted, half-dragged, and set down on the parking strip, still intact. Milton Walker built well.

Before leaving, the foreman told me to tell his crewmen to give us whatever we wanted. For a few minutes Osborne and I had the run of the wreckage, but their patience soon frayed. The day turned hot, their deadline loomed, and they remembered that civilians aren’t supposed to poke around active excavation sites. They told me to stay out and refused to set aside the agate- and geode-embedded slabs and magnificent stairs that miraculously survived the smashing and tossing. I took what shards I could snag and lift, darting in for the last when nobody was looking. One will go to the historical society’s Loghouse Museum, others perhaps to other collections or institutions. What’s left will be a memento mori in my garden.

Aftermath

The rock garden is decapitated but not all gone. It may never be entirely razed. Repin plans to keep a prominent arch below the house and cottage he’ll build and the tall “swing wall” (built with a swing for the grandchildren) below that. “We’re going to do some really nice landscaping around the arch,” he says. But these downslope fixtures rest on less secure ground than the tower and patio did.

In addition to the mountains, a swath of Milton’s stone art still stands on the lot retained by Lita and Ken Gill: walls and stairs, two ponds, the inoperative fountain, the exuberant, Hundertwasseresque “butterfly wall.” Lita didn’t respond to my queries about their plans for this large section of the rock garden. But Repin told me that “they’re planning to clear it as well. They’re going to keep the house, but she told me they want to clear everything else.” And soon. Repin says they want to get it done before his company finishes working on the adjacent lot, while they can still get access.

How big a loss will that be? Less than the demolition done last week. Much of what remains is relatively porous construction, built to hold Florence’s plantings and now open to the weeds. The Bicentennial Tower and the patio, steps and terraces below it were “the heart of the garden,” as Buffalo puts it: the most accomplished, astonishing, and durable part of the whole project.

Now they’re buried under hundreds of truckloads of other rubble in a giant pit near Black Diamond—except for the tower’s ceiling and arches, sitting across the street. John Osborne has big plans. He wants to repair them and raise a shortened version of the tower on his planting strip, directly across from the Walker house. There it would stand against forgetting as well as for delight, bearing witness and making one piece of Milton’s magic more accessible to the public than ever.

Osborne will have an uphill march getting SDOT to understand and accept that plan; the street code doesn’t contemplate rockwork towers. He may have help, however: West Seattle activists are starting to rally around this prime fragment of a shattered gem.

Still, it’s dismaying that the looming demise of West Seattle’s treasure passed under the radar in the district with the most vigorous neighborhood blog and historical society and perhaps the strongest sense of identity in Seattle. Once again, we don’t know what we got till it’s gone.

The should-haves, could-haves, and might-haves have churned in my head since then. What if I had nominated the rock garden as a city landmark? Designation wouldn’t block demolition in the end, but it would have brought attention and put up a speedbump. What if I had volunteered to pull weeds, hung around, stayed in the loop? What if I’d insisted, not just asked, that the excavators set aside those slabs and stairs? Sat in their path until they did? (Moving them would have been quicker than waiting for the police to remove me.)

Buffalo McGillvray, who worked much longer and harder to save the rock garden than I did, made his peace with its eventual fate long ago. “We did what we could,” he says. “I’m just glad we had the experience. I don’t fault anybody”—and that includes Lita Gill, the last owner of her grandfather’s intact masterwork. “My memory is of Lita, nine or ten years old, giving tours when Florence wasn’t available. She didn’t have an easy life, but she was really close to Florence. She cared about the garden.”

As for the garden, “it lasted much longer than these sites usually do. Typically they’re gone within five years of the creator’s death.”

But Milton Walker built to last much longer.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you, Eric Scigliano. You cared and you tried. I was fortunate to tour the place while it was in it’s prime. A magical project and place.

We grew up near mrs Walker gardens and would take the long steps up thru Fairmount Park play field. For years 1968-73 she gladly gave us and our friends who brought to visit tours..even thru her house,showing items not yet installed.

Did she not have moss instead of grass?? Seems I remember how cool it was on our bare feet on the hot days of those wondrous summer days in old WestSeattle..Ballard is definitely a close 2nd

Eric, this story is a tour de force. And quite sad. I fondly recall my tours of Walker Rock Garden in the 1980s and its inclusion on our Southwest Seattle Historical Society “Homes with History” tours in the early 1990s. I am grateful to note that near the end you reference “the district with the most vigorous neighborhood blog and historical society and perhaps the strongest sense of identity in Seattle.” May that reputation continue to be substantiated, in word and in deed — if not with Walker Rock Garden then to other projects such as saving the Stone Cottage on Harbor Avenue, https://savethestonecottage.org/.

Thank you for your all your work on this piece. The Rock Garden came to life while reading.

Then it was gone.

Eric, you have left me sobbing. I am so grateful to you; not just for writing this piece (shame on the Seattle Times and Crosscut!), but especially for putting so much heart, soul, and attempted investment into thus special place.

This story rips at our hearts for many reasons. Families fractured by dementia, fear of outsiders, and the soul crushing loss of a treasure.

I agree with everything you’ve said. It’s heartbreaking. I’ve only been to Seattle twice, but I would have sought this out had I known about it. So disappointing.

How incredibly sad. A legacy lost. Years of artistic creativity and craftsmanship reduced to rubble.

Thank you for all those people who stepped in at various stages to protect and preserve this treasure. You were able to breathe a few more years of life into this little-known landmark.

A real loss for Northwest arts and culture. It is so sad that no solution could be found. Let’s all put a collective bad juju fate on whatever gets built there.

I have lived in West Seattle since 1963 and no one ever said a word about this place. I would have love to take my family there…One of my grandsons is stock collector and would have been so excited to see it

I’m so sad to learn of this. Shame on you Seattle Times and Crosscut for not reporting on the impending demise of a uniquely, Seattle treasure. Though I don’t live in the immediate neighborhood, I do live in WS and would have been happy to help weed and maintain the garden if it would have made a difference. I have some friends that got married in the Rock Garden. They’ll also be sad to hear this. Another piece of WS heart and soul gone to the bulldozer. : (

Milton Burke Walker – Let’s not because whatever gets built there will likely be inhabited by a family with small children given that there is a K-5 school just below, and the block’s demographic itself has seen a shift to young families over the past decade.

I lived at the other end of West Seattle on 38th and Morgan St back in the late 50s to late 60s, and never new about this fabulous place. This is just one more ruination of the most wonderful area of Seattle. So much has been destroyed there for no good reason.

Thank you Eric for your article and your devotion to saving such a remarkable place. Just fragments remain but it was a cause worth fighting for. So sad that others did not see the treasure in their midst.

A truly remarkable work of art. I got married beneath the tower 30 years ago. My husband got to know Florence when he was an occupational therapist who would bring his life skills class at Harborview on field trips there. She was very gracious to let us have a small gathering there.

Thank you Eric for your work on this.

This is SO SAD!

But as others have said, thank you, Eric, for everything you did to save the Walker Rock Garden. You did a lot, as did other people. (“After so many dead ends, I was burning out.” I can only imagine.)

But you’ve written this amazing chronicle so maybe we in Seattle will learn from it.

And BOO to the Seattle Times for its neglect of a most important civic story. The higher-ups should be hanging their heads in shame. The same goes for Crosscut.

I had no idea that the Walker Rock Garden had been demolished. Such sad news as I woke up this morning with the idea of how cool it would be to tour the garden with my family. I googled Walker Rock Garden and found your story. I toured the garden back in the 1980s, such a magical place. Thank you for fighting for the garden’s preservation. Now I am wondering if a book was ever created with photos of the rock garden. I would love to have a book like that to share with my family what the rock garden looked like.

“a roadside rock-shop owner in Oregon offered to sell his 10-ton stock of agates”

So that’s what became of Rocky Joe’s. We always wondered where it went. Sad story on both accounts.

Eric Scigliano knows how to write the sacredness of places — whether it’s the Fraser River, or a local “fragment of a shattered gem.”

Eric,

Was just looking online to see if visits were still allowed at WRG.

So devastated to learn of its DESTRUCTION!

Do you know where any of the segments ended up?

Here is one thing that might cheer you:

You wrote the first city-wide article, regarding what became the Belltown P-Patch.

I cold contacted you by phone, at the Seattle Weekly.

A white MUP sign had been erected on the site, the precursor to development. Just as we had gotten the City to begin negotiations to rent it for community gardening.

You interviewed Mike Woodwell, who lived in one of the now restored and protected Belltown Cottages, next door. Probably about 1989 or 90?

Ring any bells?

Anyhow, as a group of us founder-creative-volunteers were deciding the overall layout and design of the park/public garden…we visited several existing locations, to collect good ideas. Everyone loved that excursion, it gave us a foot up on identifying desired features/characteristics to build.

The unanimous favorite, was Walker Rock Garden which few of us had ever been to.

It actually is a spiritual parent to the ongoing

Belltown P-Patch, which opened to the general public on 1995’s Summer Solstice.

Soon the new Seattle Waterfront will be fully functioning, the Patch at Elliott and Vine, is smack dab between the Market and the SAM sculpture Park.

I encourage you and everyone to stroll through on a pretty day, the spirit of Walker Rock Garden LIVES!

I thank Gaia for all Outsider Art Champions and look forward to the relay torches that are passed forward.

My love and Gratitude/Respect to YOU, Eric:

Such a true Seattle Citizen. 🙏🧜🏽♂️