In late 2019, when producer AEG, the country’s biggest music promoter, stepped away after five years of producing Seattle’s iconic Bumbershoot Festival, it was an admission that the event had become unsustainable. Founded in 1971, Bumbershoot had drawn as many as 325,000 fans to the Seattle Center grounds for the annual Labor Day weekend event. By 2019, tickets for the once-free celebration had grown to $220 and audiences had shrunk to 30,000. (My Post Alley colleague Jean Godden recently wrote about the City Council’s decision to save Bumbershoot and hire AEG after 2014’s $900,000 loss, a decision she says she’s grown to regret.)

Scrambling to regroup after AEG withdrew, in February 2020 the City announced it had enlisted One Reel, the once legendary Seattle producer and longtime steward of Bumbershoot in its heyday, to once again produce it. Of course, the 2020 festival was almost immediately canceled after COVID hit, but there were assurances that it would return in 2021 for Bumbershoot’s 50th anniversary.

A few weeks ago came the announcement that 2021 wouldn’t be possible either – unfortunate but probably understandable given uncertainties over safe resumption of live events. But look a little deeper into the announcement and there’s alarming evidence that City leadership doesn’t have a clue about how to revive Bumbershoot. Beyond the rote de rigeur blah blah about “maintaining the Festival’s essential character of artistic and cultural diversity and excellence and the tradition of strong community festival involvement,” there was nothing to suggest the past year has produced a well-thought-out plan for the event.

In fact, in the cancellation announcement, the City announced the formation of a new “exploratory committee” to “inform and advise the Seattle Center Director about Bumbershoot’s future.” A year-and-a-half after AEG withdrew. A mere six months before what was supposed to be the 50th anniversary festival.

What?

There were concerns when the City asked One Reel to take over Bumbershoot last year whether it still had the chops to do so. The company, once one of the most creative and inventive forces in the region, had shrunk from more than 50 employees to a handful. A glance at One Reel’s website shows its current activities consist mainly of managing a Pianos in the Parks program, the occasional special event and a small Art Saves Me initiative. Hardly big-time producer cred.

Nonetheless, One Reel is Seattle cultural royalty and probably deserved a chance to pull it off. Booking and producing talent can be hired in the service of really good ideas. But a year-plus into the project the fact we’re just now getting around to forming an “exploratory committee” and that there’s not some serious plan well underway is a very bad sign.

The modern festival is not something that comes together in a few months, or even a year if it’s starting from scratch. The music festival model AEG had been using — big name acts, big price tickets — has been broken for a while now, so a renewed Bumbershoot – no matter its glorious history – has to be reinvented. That means essentially creating a completely new model in a competitive and challenging environment. That’s a big hill.

So what happened to the old music festival model? It used to be that big-time musicians toured to support sales of their albums, which is how they made most of their money. Live concert fees, though never really cheap, were negotiable because the musicians would make it up on the recording sales on the back end. But with the internet and streaming, musicians now make little money in recordings. So, as I wrote over a year ago in Post Alley:

“Over the past 20 years there has been an explosion in the number of festivals around the world. Thousands of them sprang up, some becoming giant franchises. Miami’s Ultra dance music festival bred editions on three continents. Coachella, Bonaroo, Glastonbury, Outlands, SXSW, Governors Ball, Lollapalooza, Pitchfork, Burning Man and others have become aspirational destination events that sell out within minutes and cost hundreds of dollars to attend. California’s Coachella, one of the biggest, earned $114.6 million over two weekends in 2017. Sydney, Australia’s annual festival takes over the city and attracts 1.4 million participants. Billboard reported two years ago that 32 million people attended festivals in the US that year.”

The big festivals became an international circuit and a lucrative source of income for musicians. Fees skyrocketed. Theoretically, AEG was in the best position to make Bumbershoot work, given its scale and clout to book top acts. But the economics – as with many midsize festivals trapped in the cost spiral – still didn’t work. And artistically, the model has been in decline, anyway, as once-unique festivals became increasingly generic.

So it’s no surprise the City is making noises about trying to revive the local quirkiness that initially made Bumbershoot such a success. Probably the biggest buzzwords in the arts right now are about the need for local authenticity to reflect, include, and engage community. Had new Bumbershoot producers been working on what that model would look like and involving the community in planning this past year (even during COVID), then there would be cause for optimism.

The fact that a whole year has gone by, during which the public has heard and seen nothing, and a committee to “advise” on the future of Bumbershoot is only now being formed — is an indication that there’s no creative spark at the center of this reinvention. This reads more like a performative Seattle collaborative exercise rather than civic and cultural leadership. The reality: You can’t produce creative vision by committee.

The irony is – given the lockdown of the past year and the halt to our shared civic life – a creative festival is perfectly positioned to capture the attention of the city and primed for success. A surprising number of the world’s biggest and most successful (and long-running) festivals were born out of crises. The Edinburgh Festival, one of the largest and most creative, for example, was started in response to World War II and the desire to assert the resilience and creativity of the Scottish people.

Seattle, a wealthy city built on the creativity of its workforce, would come together around a collective expression of that creativity, as it did in the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific exposition in 1909, which drew 3.2 million, and the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, which kickstarted many of Seattle’s cultural institutions. Bumbershoot itself was born in reaction to the Boeing Bust which had devastated the region. Then-Mayor Wes Uhlman initiated that first festival as a way to try to rekindle civic spirits. It worked.

In that earlier Post Alley article, I listed a series of suggestions about how to rebuild Bumbershoot. Here are three more, given that we’re a year later and the door is closing quickly on 2022:

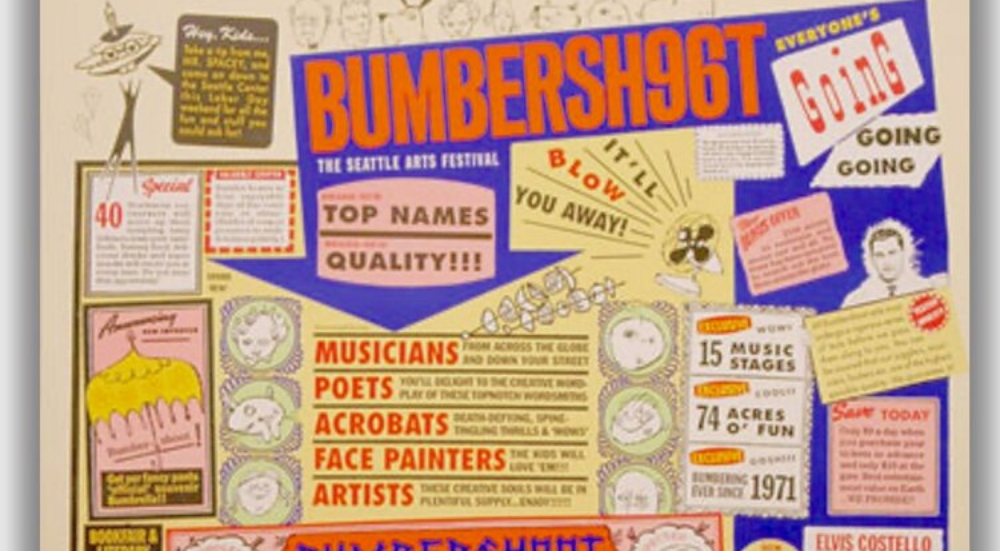

- Abandon going big: The original Bumbershoot was called Festival ’71. Boring. It had a teeny tiny budget: $25,000. Both played down expectations. Bumbershoot lore has it that festival director Anne Focke spent fully a fifth of that budget on a laser show, which was at the time a futuristic and unique experience. Wikipedia reports that other attractions included “computer graphics, enormous inflatable soft sculptures by the Land Truth Company, an electronic jam session, dance, theater, folk music, arts and crafts, art cars, body painting, a Miss Hot Pants Contest, amateur motorcycle races, and only one out-of-town performer: country singer Sheb Wooley.” The quirkiness of the idea (and the fact it was free) attracted 125,000 people, vastly exceeding expectations. Its success drove 175,000 to Seattle Center the next year. So shrink down. Get rid of the bloat. Abandon the big fees. Start over and try a bunch of stuff and see what works and build on that. That $25,000 is worth $164,848.15 today. Make the budget a creative challenge and relaunch in the original spirit of throw-it-against-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks experimentation. What’s the technology that’s the Wow equivalent of the laser show? What’s uniquely local that’s here and deeply cool and deserves celebrating with a bigger audience?

- Don’t compete, facilitate: Our artists, concert halls, galleries and event producers have been slammed by COVID shutdowns. A new Bumbershoot shouldn’t just hire artists, it ought to give them opportunities to do things they couldn’t do on their own. In other words, rethink the idea of being simply a presenter. Facilitate creative connections between sectors that don’t take place elsewhere — between artists and technologists and thinkers – these wouldn’t be just talk, but projects that come about from atypical collaboration. A Bumbershoot experience ought to be identifiable, unique and memorable. Articulated right, Bumbershoot would set a high bar and be the gig artists fight to be a part of.

- No generic anything ever: Just as generic music festivals have grown stale, generic concerts, generic food and generic arts experiences don’t cut it. A Bumbershoot experience ought to be an experience you couldn’t have anywhere else and is reinvented every year. Not one curator, but a series of overlapping curators who collaborate and compete. You can’t do this by committee. It can’t be driven by an event-booker. The ideas need to be audacious and designed and scaled to the community. That first Bumbershoot was quirky, had a microscopic budget, and drew three times as many people as the bloated and expensively generic music festival that Bumbershoot had become in its last year. Take the lesson.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Seems to me Bumpershoot should abandon the Labor Day Weekend, since the weather is too chancy. I would also spread it around to more venues that Seattle Center, whose large facilities are often booked by others and the wear and tear on the grounds is severe. Think Marymoor, the new Waterfront Park. And I would see if Seattle Theatre Group and Josh LaBelle could step up to the producer challenge. And who’s in charge? Like the 1962 World’s Fair, there needs to be a special entity created, escaping all the vetoes of Seattle politics.

As I meant to spell, Bumbershoot. Shoot me!

Creating an “exploratory committee” is most often a way of doing nothing. It’s so sad to read about the bumpy journey toward oblivion of Bumbershoot. Let’s hope your suggestions reach the ears of people who can make them happen.

Thanks for the fine writing and clear- eyed analysis, Doug. I never missed a Bumbershoot ’til AEG cane in. There was always something for everyone: kabuki theater, literary events, crazy art installations, ballet, rock, blues, outer-planetary jazz. And it was affordable. I hope there’s a maestro somewhere in there who can stir up more of that eclectic magic.

Once again, a roadmap with special insight. The city needs real partners, not new commissions and exploratory committees.

Exploratory Committees are almost always just a way to say “we tried crunching the numbers from every angle and just couldn’t make it work”. This should be a huge red flag and cause for the task to be reassigned to more capable hands. I would love to see something more community/artist driven, ideally something like having a big local artist/band like a Pearl Jam or someone of that caliber use their considerable contacts to form a collective and reach to put together something truly unique and special and then (just as carefully and considerately) pass the torch to someone else to do the same for the next year. I’m sure this is huge pie in the sky thinking, but it seems like for as big a nut to crack as saving or reinventing Bumbershoot will be, big and crazy ideas need to be on the list for consideration. There’s no point in trying to be another Coachella or SXSW or anything else that isn’t uniquely Seattle and expressive of the DNA that makes this city what it is (although maybe we are also due for a harsh truth that what we are is boring and predictable, but that’s another issue altogether). Out there, away from the cranes and the corporate shitbirds that have tried to become the Seattle identity, there lurks a vital and thriving creative community that yearns to be recognized and counted among the things that make this place so special, while it’s all well and good to lure talent from everywhere, a reborn Bumbershoot should first and foremost cater to being a showcase for Seattle to show itself to the world and shine. Hopefully committees and one-upsmanship to create the next “aspirational event” don’t choke the last vestiges of life from what could be a truly special event.