In Daniel James Brown’s compelling new book Facing the Mountain: The story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II, the reader follows Rudy Tokiwa from a desert concentration (“internment”) camp in Arizona, to heroism on the Italian front, to arrival in San Jose, California, seeking to track down his parents. The Bronze Star winner, in uniform, asks for help from a woman at a bus stop Red Cross aid station. “There’s a place on Fifth Avenue: A bunch of Japs are livin’ there,” she told him. He found his folks at a Buddhist temple.

Facing the Mountain (Viking, $30) is a story of humiliation and triumph, of American citizens and immigrants taken from an “Exclusion Zone” along the West Coast because of their ancestry and shipped to camps. The post-Pearl Harbor “internment” was ordered by our most progressive president, Franklin Roosevelt, backed by a future human rights champion U.S. Rep. Henry Jackson who warned of the “disciples of Bushido” endangering the West Coast, and supported in rulings by liberal Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

Having put them behind guard towers, the U.S. government asked the young men to volunteer and fight for the country. They debated, most enlisted, and many proved to be superlative soldiers. Arriving on what Churchill had called the “soft underbelly” of the Axis powers, they found Italy to be, as one general put it, “a tough old gut.” The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, after battles in Italy and France, emerged as the most decorated military unit of its size and length of service in American history.

As witnessed in his previous book, The Boys in the Boat, Brown is a writer who believes in total immersion. He tracks down people and records, follows 442nd veterans up hills in what was the Germans’ Gustav Line in Italy, and gets in the heads of people like Rudy Tokiwa. The result is reading that will stay with you. Tokiwa receives his Bronze Star at a ceremony in Italy, as soldiers march past and salute him. Thoughts go back three years to the Poston concentration (“internment”) camp in Arizona:

“He had been angry then – angry at the country that had incarcerated his family, that had humiliated his parents, that had cost them their farm and their livelihoods, that had treated him as a second class citizen.” Yet, there was the competing feeling of peace and pride. “You know, he thought, it’s coming out to be, it doesn’t make no difference what you look like. It’s what you’re doing and what you’ve done for the country that counts.”

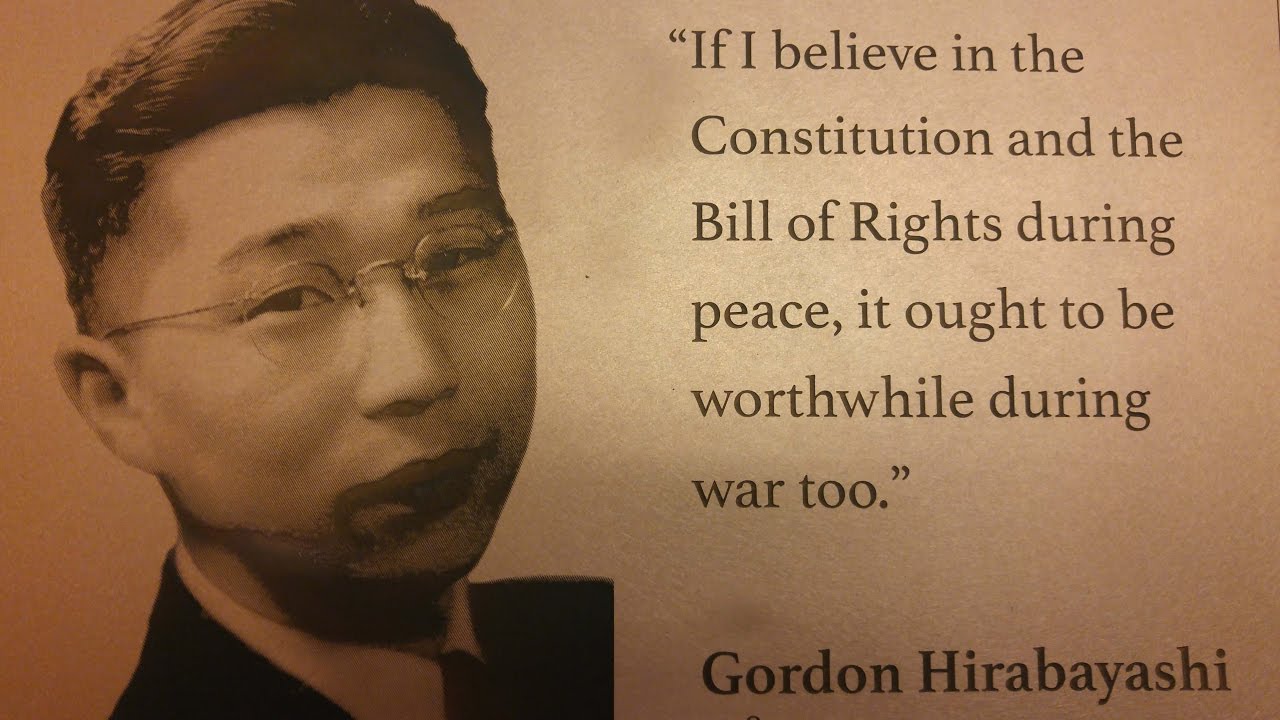

Facing the Mountain offers faces, some familiar, of both warrior and peacemaker. Gordon Hirabayashi was a University of Washington senior and a Quaker who fought federal internment in the courts, and questioned the rules even when incarcerated. He was, for instance, put in with white inmates in segregated barracks. “What is your basis for barracks segregation: Why was I put in white barracks?” he asks camp administrators.

When his last appeal ran out, Hirabayashi was assigned to a concentration (“internment”) camp in Arizona. Such a threat to national security was he that Hirabayashi was simply told to make his way across the West to a camp in the Catalina Mountains of Arizona.

Fred Shiosaki had hoped to live to see publication of Facing the Mountain, but died last month at the age of 96. He faced the mountain, as the 442nd broke through to rescue a battalion of Texans cut off and surrounded by Germans in the Vosges Mountains of eastern France. A blustery, overmatched commander, Gen. John Dahlquist, ordered the Nisei to charge up a slope filled with German machine gun positions. Shiosaki would receive a Bronze Star and Purple Heart. During the month of October in 1944, writes Brown, “the Nisei soldiers had taken 790 casualties, the largest number” in rescuing the Texans.

Shiosaki had just started college in December of 1941, while working in his parents’ Spokane laundry. After the war, he would complete a degree in chemistry, serve as founding director of the Spokane Air Pollution Control Authority, and serve eight years on the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission. He was father-in-law to former Seattle Mayor Ed Murray.

The book also tells of a young officer named Daniel Inouye, directing an advance even as a rifle-launched grenade severs his arm. As men gathered around him, Inouye ordered them to resume the attack, growling “Nobody called off the war.” Inouye would go on to serve in Congress more than four decades, most of his tenure as a U.S. Senator from Hawaii. “Danny”, as colleagues called him, was the most prominent of young war veterans who returned home to shake up Hawaii’s once sleepy state government and champion the cause of statehood.

Immigrant sagas are integral to American culture, from “The Godfather” to Timothy Egan’s fine book The Immortal Irishman. Most deal with Irish refugees fleeing Brit-caused famine, Russian Jews who escaped pogroms, and Slavic immigrants who found a rough new life working in mines and steel mills. The new Brown book traces a less familiar group who crossed a larger pond – the Pacific Ocean. Seeking escape from hunger and poverty, Japanese emigres labored in the sugar fields of Hawaii. Or they ventured to the Mainland. On Bainbridge Island, 221 persons of Japanese ancestry, mainly farmers, were given six days to “evacuate” with only what they could carry.

The traditions of an ancestral homeland, notably a family’s sense of sense of honor, came to play as young men went off to war. But those in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team came to exemplify the ideals of their adopted country, never succumbing to bitterness despite the racism to which they were subjected. Writes Brown:

“Those young men were the living embodiments of the spirit that has always animated America, the spirit that has held us together for more than two centuries – the striving, the yearning, the courage, the relentless optimism, the willingness to chip in and lend a hand, the fair-mindedness, the inclusiveness . . . But do not forget this. As American as they were, in some ways and in varying degrees, they were also proudly Japanese. As they stood up and ran into the fire, many of them carried with them values that their immigrant parents had taught them – not just the samuri’s code of Bushido, but a host of related beliefs and attitudes – giri and ninjo among them.”

“Giri” is the Japanese concept of duty and obligation, specifically the obligation to serve one’s superiors. “Ninjo” is the belief in human feeling and compassion. Of the Nisei soldiers, writes Brown, “It was largely because they held these other ‘foreign’ values that many of them were able to do what had to be done.”

Words upon which to reflect, in this era of renewed American nativism in which when a former President, his political party and pundits on Cable TV deliver the dog whistles of white supremacy. Japanese-American soldiers fought on the battlefield for the ideals of a country that had treated them shabbily, while some like Gordon Hirabayashi fought for them in hostile courtrooms.

The country in which returning veterans were “still ‘Japs’” eventually came around. With Rudy Tokiwa lobbying the U.S. Capitol, Congress voted to partially compensate surviving detainees. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 declared the wartime incarcerations “were carried out without adequate security reasons” and “were motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” President Reagan signed the bill into law.

Just one member of the 442nd was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor during World War II. In 200, President Clinton conferred the nation’s highest honor on 20 other members of the regiment, some posthumously. Sen. Inouye became a Medal of Honor recipient, as did William K. Nakamura, for whom Seattle’s old federal courthouse was renamed.

We have places to reflect on lessons of Facing the Mountain. One is the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, run under auspices of the National Park Service. A second, reconstructed barracks and a beautiful garden on Slocan Lake at New Denver, British Columbia, to which Japanese Canadians were “evacuated” in World War II. A favorite of mine is the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site, halfway up Mt. Lemon on the Catalina Highway above Tucson. You can camp and picnic and walk to exhibits on the concentration camp to which the young student reported.

The U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals would later void his conviction, citing suppression of evidence at his original trial. In 2012, a few months after Hirabayashi’s death, President Obama posthumously conferred on Hirabayashi the Presidential Medal of Freedom and quoted from the honoree: “Unless citizens are willing to stand up for the Constitution, it’s not worth the paper it’s written on.”

The publication of Facing the Mountain, on sale May 11, is a teaching moment.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A footnote: While ex-Seattle Mayor Ed Murray was Fred Shiosaki’s son in law, son Michael Shiosaki was a longtime Seattle Parks manager and is Bellevue Parks director. Achieving family.