President Biden wants to get local governments to unlock their strict zoning laws. Minneapolis has scrapped strict single-family zoning. The California Assembly repeatedly tries to force local governments to allow transit-oriented development.

All good things to relieve the under-building of housing in the country, but all are fighting the wrong wars. These changes are aimed at just one part of the housing market: apartments and condominiums. The first problem is, most Americans don’t live in multi-family housing and most don’t want to. Second problem, the supply of single family houses is not keeping up with demand in large parts of the country. Third problem: in the Seattle area, where single family housing prices are marching upward into double-digit territory again, apartment construction has been furious.

Adding these factors up, it’s clear we have an affordable-apartment problem, but we do not have an overall apartment-supply problem. What we do have is a single-family supply problem, but it does not get discussed much or is politically off-limits. Nonetheless, housing-policy solutions always seem to steer back to multi-family, where there is both an over-supply and a lack of demand.

Let’s do the numbers. Figure 1 shows the occupied housing stock.

Combining single-family detached and its close cousins, townhouses and duplexes, we find about 70 percent of the nation and state live in these, with 30 percent in all other housing forms. Within the 3-county region, the picture is somewhat varied. In King County, 60 percent of households live in single family/townhouses, while more than 70 percent do in Pierce and Snohomish. King County has emphasized apartment construction, and the adjacent counties have absorbed demand for detached housing. Also of note is the share of King County residents in the largest multi-family complexes.

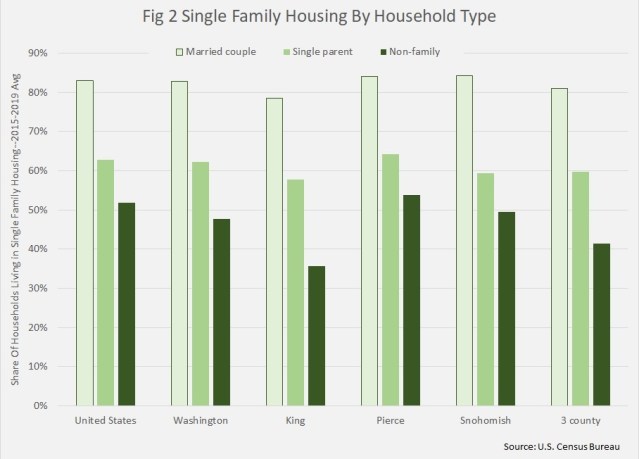

Figure 2 shows the propensity of various types of households to live in single family housing (in figures 2, 3, and 4, single family includes townhouses, but not duplexes).

Among married couple households of all ages, with and without children, over 80 percent live in single family homes in the region, with slightly less than 80 percent in King County. Single parents are more likely to live in apartments. Non-family households, which consist of either single person households or groups of unrelated people, are also much more likely to live in apartments.

Figure 3 shows the rate of single family living by age group.

This seems to cast doubt on the notion that large numbers of seniors and empty-nesters would give up their single family homes to live in convenient, exciting, urban centers (the data do not include people living in institutional settings such as nursing homes). In the 3-county region, 67 percent of those over 65 still live in single family homes, and that only dips to 64 percent in King County.

Figure 4 shows the propensity of the smallest household (one or two residents) to live in single-family housing.

One observation: There are a lot of empty bedrooms out there, since 40 percent of one-person households live in single family housing, and two-person households live in single family homes at almost the same rate as the population as a whole.

This picture has not changed much over time. In the past decade, apartment living has increased quite a bit as a share of the total in King County, but actually decreased in the two adjacent counties. The slight growth in the apartment share region-wide is likely tied to the rapid growth in the population of younger people who, as seen in Figure 3, tend to live in apartments.

Looking Ahead

The important facts to emerge from these data are that we have several serious mismatches in the housing sector. Construction of single-family homes in the region is not keeping up with population growth. Furthermore, those priced out of single-family housing in the areas where they would like to reside will not tend to settle for multi-family living. Multi-family is seen as a poor substitute for single family, so households will tend to seek such substitute neighborhoods, engaging in the “drive to qualify” pattern that has come to be the norm for middle-income households. But drive-to-qualify, a spur to sprawl and inefficient land use, has another growing problem: prices are increasing rapidly in the more affordable parts of the region.

This story previously ran in our partner site Puget Sound Indexer

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.