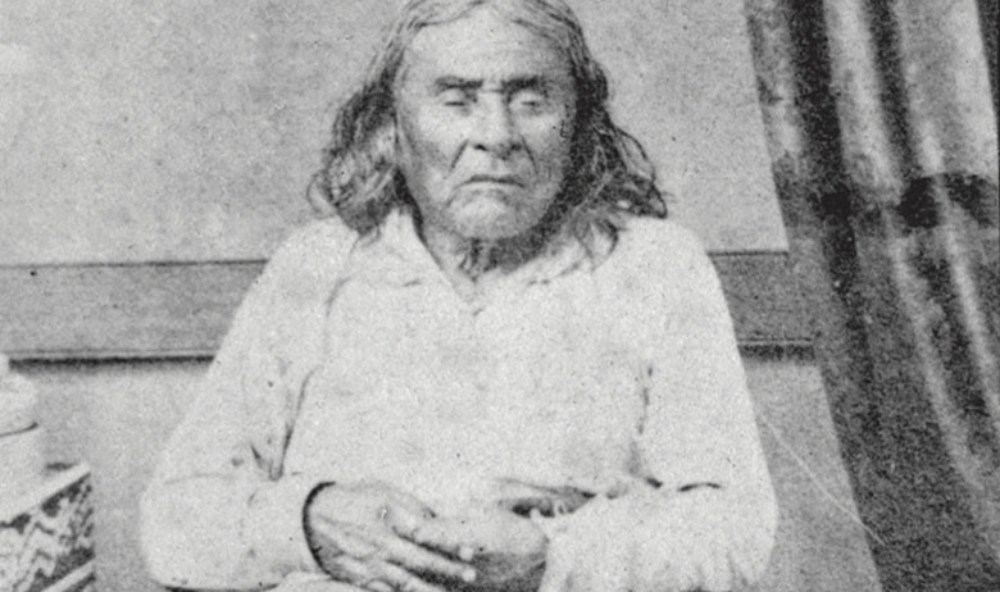

Among the lesser-known facts about Chief Seattle is that he owned slaves, as many as eight. He carried out slave raids and sold or traded those he captured. He freed his slaves as required by the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, but many chose to remain in his service, and some outlived him.

Many are surprised to learn that this revered figure and namesake for the city was a slaveholder and a frighteningly bellicose warrior. They were taught to regard him as a peace-making conciliator, a “friend of the whites,” as, indeed, he became in his later years. His owning of slaves cannot be minimized, but to understand its role in Puget Sound native society, some humility should attend our urge to levy severe judgments on figures from our past.

Slavery was part of Northwest Coastal culture and society. Puget Sound traditional society had three general ranks: See AHB, noble; QUH qul, commoner; and STU duq, slave. Early anthropologist Thomas Talbot Waterman estimated that one third of the people were See AHB. His colleague Philip Drucker wrote that the rank of noble was endowed with privilege and ceremony — but not office, since See AHB exercised little actual authority.

Slavery was ancient, appearing thousands of years before. It was among the traits that made the culture of the Northwest Coast distinct: an unusual fishing, hunting and gathering economy; a populous, stratified society based on kinship that valued property and gift-giving; and a rich ceremonial, artistic, and religious culture. In the Puget Sound region, these traits evolved somewhat differently, and some people developed agriculture, including the domestication of mollusks. These traits were described by western observers and anthropologists, but increasingly, native scholars and writers are redefining and reconfiguring our understanding.

The presence of slaves in myths marks its antiquity. In one local myth, as a family crosses Puget Sound in a catamaran to a temporary camp, Crow, a household slave, sits astern carrying a bentwood box filled with drinking water. In another, Raven, North Wind’s slave, punishes an old woman by defecating on her face.

Unlike further north on the coast or at the mouth of the Columbia River, slaves on Puget Sound were mostly household servants accounting for, at most, one or two percent of the population. Once children left the nest, taking their labor with them, a family might use a slave to help maintain a household. Slavery probably developed as early northwestern societies invented advanced technologies that required labor-intensive skills and a growing population was organized into effective social hierarchies. Slavery supplied labor outside one’s kin group, but also provided a means for kin to pay off temporary debts via indenture.

At its most violent, slavery took war captives, generally women and children that were traded and put to work. In the 1530s, Spanish castaway Cabeza de Vaca owed his life as a shell-trader to the native society that kept him alive by enslaving him. Likewise, two Spanish blacksmiths marooned on the Oregon coast survived because local groups valued their ability and let them live as slaves. Their shipmates with less useful skills were killed.

Chief Seattle’s own past provides another example. Catastrophic mortalities produced by virgin epidemics introduced by maritime traders on the Northwest Coast in the 1780s and ‘90s caused native societies on Puget Sound to crash. This disaster was accompanied by the introduction of firearms, primarily by American fur traders. As groups struggled to reconstitute themselves, violent slave raiding and trading increased.

One of Chief Seattle ‘s grandmothers, captured during a raid, was later ransomed, but the taint of slavery stayed with her and her offspring including one of Chief Seattle’s parents. Writing in 1854, Oregon Territorial Indian Agent, Edmund Starling, noted of him: “His father was a chief or Tyee and his mother…a slave. He is chief at present of the Suquamish Tribe. ‘Tis a stigma, however, upon him, which were it not for his own good sense, would take much influence from him that he otherwise would have.” That heritage continued to haunt him after his death in 1866. Nearly a century later, a Skokomish nobleman who became a long-term Washington State legislator, George Adams, derided Seattle as “…an ex-slave who grew up in Fleaburg.”

The Chief’s birth village is a place called Ch OOT up ahltxw, “Flea’s House,” (rather than Adam’s Fleaburg), located on the lower White River near the City of Auburn In a myth about the place, Elk Woman married Flea and moved to his village. He and his people were giants. The residents took a disliking to Elk Woman, trying to suffocate her by burning fresh bones on their fires. But she attacked them, ripping them to pieces with her teeth and splashing the interior of the house with their blood. Their drops of blood came back to life but, fortunately for us, only as little nuisances (fleas). The village had four large longhouses sheltering as many as 100 people and their chief. Having a village myth suggests noble ancestry, but this one may have been intended as a put-down by newcomers who took up residence on the river a mile north on them.

Sometime late in the 18th century a great flood left an enduring log jam at Flea’s House that extended a mile down-river, effectively blocking canoe traffic. In Whuljkootseed, the word for log jam is Stuq. Shortly afterwards, five noble families from the Black River at Renton literally pulled up their house posts and re-erected their village at the northern end of the jam, giving them effective control of river traffic. Called the Stuq AHBSH, “Log jam People,” they were haughty and arrogant, soon in conflict with surrounding groups. It is possible that Flea’s house was decimated by disease and lost many nobles or parents, making its children orphans and poor marriage choices. Its site is now developed, although archaeology may still provide clues.

Gradually, the village lost status. The Log Jam People treated its people “like slaves”—like fleas if the story was meant as a slur. Seattle’s mother was said to have belonged to the Log Jam People and may have been a member of one of the noble families. Seattle’s name came from one of her ancestors, his inheritance of it a mark of noble pedigree. His father was said to be Suquamish, a brother to K TSAHP, Kitsap, a famous war leader. But another tradition claimed that both parents were from Flea’s House and were cousins, low-class relations for marriage.

Fleas’ House was endogamous; marriages came from within the group as opposed to being exogamous, where village members married outside the group—a hallmark of nobility. Endogamy was not unusual, particularly if a village were large, but it marked Flea’s house as QUH qul—common: low or useless people, treated like slaves. Seattle grew up at Flea’s House, gaining a reputation for intelligence and openness but also a violent temper.

Becoming a war leader gave a man with such an ambiguous background a chance to achieve fame, status and wealth. Seattle took this up with a vengeance beginning in 1810 with a famous ambush of raiders coming down the lower White river in canoes. Seattle and his supporters ambushed the raiders in a bloody melee near present-day Tukwila. He participated in a great raid as part of an alliance engineered by Kitsap who led an armada of 200 canoes against Cowichan slave raiders on Vancouver Island that had harassed Puget Sound groups for years. Although a tactical defeat, the assault enabled alliance members to establish a peace with the Cowichan, which was successfully maintained through intermarriage.

Other raids followed in Seattle’s typical style: ingenious, bloody and successful. These climaxed in a great raid on the Chemakum People near Port Townsend around 1845 from which the Chemukum never recovered. Hudson’s Bay Company officials feared and did not trust the old chief. That was the year Americans began settling north of the Columbia River. Their numbers had been growing in the region for decades and in 1847, they went to war and defeated the Cayuse and their allies in eastern Oregon after killings at the Whitman mission on the Walla Walla River.

Native concern over disease and growing settler numbers led to violence west of the Cascades, and in October, 1849, Oregon Territorial Governor Joseph Lane held a dramatic show-trial at Steilacoom Barracks near Olympia during which two native men were convicted of murder and hanged the next day. This happened in the presence of hundreds of native people required to witness the event. The Americans believed they had humbled the native people, and some native leaders decided to switch tactics.

None more so than Chief Seattle, now nearing his 70s. In Puget Sound society, if a new and vigorous group showed up, one might have to fight them, but one could also intermarry with them, sharing in their vitality and mitigating violence. That is what had happened with the Cowichans in the 1820s, and Seattle set to work immediately to bring this about in his homeland around Elliott Bay. He moved as many as 200 of his Duwamish people to the recently established settlement of Olympia — a place Americans called “Chinook Street” because that trade jargon had become the primary means of communication between the races.

As a successful war leader, Seattle had contacts throughout the region and looked for Americans he regarded as useful to his plans. Some of these were notable figures such as Benjamin Franklin Shaw and Isaac Ebey, the latter writing a widely-read newspaper article extolling their reception among Seattle’s people. When word got out that Seattle’s Duwamish River homeland on the east shore of Puget Sound beckoned, John Holgate, Luther Collins, Henry Van Asselt, and Charles Maple became King County’s first settlers. In 1850 Chief Seattle brought San Francisco commercial merchant Robert Fay to Elliott Bay to help organize a fishery and export barreled salmon to the Bay Area and Hawaii, the first commercial venture on the bay, a year before the city was founded.

That summer Chief Seattle had 700 native workers catching, preparing and barreling salmon under the guidance of a Swedish cooper, George Martin. In late summer, 1851, Fay accompanied pioneers David Denny and Charles Terry to the fishery, and it was there that Denny wrote his brother Arthur, recently arrived in Portland by wagon train, “There is room for a thousand people. Come at once.” In November 1851, the 24-member Denny Party—12 adults and 12 children—arrived and received Seattle’s protection.

When much of the first salmon cargo rotted on out-bound voyages, Fay left town, and Seattle returned to Olympia to find a replacement, Doctor David Maynard. In March Seattle helped settlers build cabins on the east shore of the bay, near two large native villages. Young white men leaving Californian gold fields eagerly intermarried local native women. As the two races learned to live and work together, Seattle’s multicultural vision took shape.

By August 1852, the place was booming, and local settlers unanimously decided to name their new town after their patron and protector: Chief Seattle. Unfortunately, other Americans not so enthusiastic about native leadership arrived in increasing numbers, and violence between the two races resumed in 1855 with the Yakima War.

Seattle was often seen on Puget Sound in his great canoe propelled by teams of paddlers, some of whom were his slaves. Some may have become his concubines, women offered by those who, unable to assemble dowries, wanted connection with a great man. He is known to have married at least four times. As he approached other canoe parties he would announce himself in a booming voice, “Ut tsAH, See AHT tlh, It is I, Seattle!” proclaiming his peaceful intent. In the early years of settlement, Seattle became the town’s impresario, its indispensable man.

Although he labored mightily to achieve it, Seattle’s vision of a prosperous, racially hybrid society failed to materialize on Elliott Bay. As settler numbers grew, the weight of American violence, hubris, and racism smothered that dream. In 1865, in one of its first ordinances, the newly incorporated town of Seattle, once a prosperous native village with a small white neighborhood, banned native people from living independently within its limits. Against their desires, Seattle and his people were exiled to the Fort Kitsap (now Port Madison) Indian Reservation on the west shore of the Sound, where, a year later, he died. No local newspaper (Seattle then had two) mentioned his passing. Seattle freed his slaves as directed to by Article X of the Treaty of Point Elliott, signed by native chiefs on December 22, 1855. Seattle’s slaves stayed with him, including old Yutestid and Billy Clams at Suquamish.

Even as a slave owner, Chief Seattle does not appear to have been a racist. The same native society that kept slaves also valued racial cooperation and intermarriage. Native Americans intermarried with white, Asian, and African-American settlers, valuing character and enterprise over skin color. That is one of their great cultural gifts to American society and remains an integral part of Chief Seattle’s epic vision.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Excellent. Youm managed to sum up a pile of history in fine style.

Fascinating story, David. This, like your book, covers material that we haven’t seen elsewhere a Even those of us who have tried to inform ourselves about the Seattle’s early history, have much more to learn.

By the way I’m not making light of this. I’m trying to raise a very serious point and that’s the Kendi anti-racism approach is not going to work… Big subject obviously can’t be done in comments. But I think we should be talking about Chief Seattle ….And why nobody would even think about taking down the statue even though he was a slaveholder….Justice Roberts was entirely wrong when it came to that specific voting rights decision but his punchline was absolutely correct. He just had misunderstood the timing.

Racism and slavery aren’t the same thing. The bitter fruit of America’s slave holding past is due to its combination with racism – slavery, per se, is just a historical curiosity, and its widespread historical practice isn’t going to cause any statues to fall (Ancient Greece, Rome, …) We sure don’t accept it today, but we put figures of the historical past on trial only when it’s our race slavery, the practice that left this poorly healed scar.

I can’t begin to describe how odd it is that modern academia worships depravity as long as it isn’t associated with whiteness or America.