In January 1856, warriors left villages on the upper Yakima River to snowshoe across the wintry Cascades. Led by Owhi, a Yakama war leader, the warriors took several days to make the crossing to the winter village of EESH qwow (Issaquah) where quarters had been prepared for them.

Rested and resupplied, they crossed a hilly trail to the village of SAH tsah kahl, behind a great marsh on the eastern shore of HAH chu, Lake Washington. A myth about this village told how Mink prepared a trap to catch Ruffled Grouse, a figure associated with the Land of the Dead. The heavily armed men were planning a deadly trap of their own.

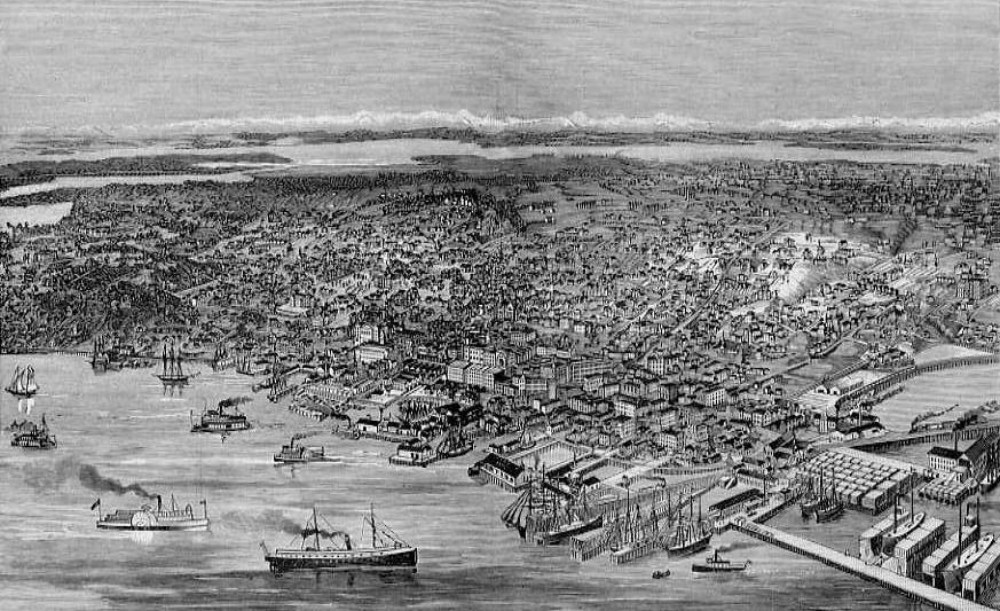

This attack force was made up of fighters from east of the mountains, known generally as Klickitats, up-river Duwamish, Lake Washington and Sammamish River and Lake People. On the 24th of January canoes ferried them to an assembly area on the western shore of Lake Washington to prepare an attack intended to destroy an American settler town named after the Duwamish chief, Seattle.

The attack was part of the larger Yakima War fought between native groups and Americans throughout Washington Territory from 1855 to 1858. The idea for the attack on Seattle came earlier in December when the armed sloop U. S. S. Decatur, whose look-outs were scanning the horizon for hostile northern raiders, slammed into a reef off Bainbridge Island, later named Decatur Reef. The accident punched a hole below the waterline and shattered internal timbers. Decatur was then beached at Yesler’s Wharf in town, its upper masts removed and guns and stores placed on the dock during repairs.

To native observers, Decatur’s misfortune was an extraordinary boon. If an attack could be mounted in time, her stores might be seized and both ship and town destroyed. Plans were made to make it happen.

This summer the modern city of Seattle will have a chance to locate and examine this lakeshore assembly area, the setting for the greatest armed assault ever made on the town and an event that changed its history. The Seattle School District plans to carry out construction of four new classrooms at the site of Leschi Elementary School, bordered between E. Yesler Way and E. Spruce Street and 31st and 32nd Avenues, northwest of Leschi and Frink parks, about a quarter mile inshore from the lake.

In this area, 50 to 100 men assembled in temporary shelters back from the lake to avoid detection. They brought scores of firearms and hundreds of rounds of ammunition as well as incendiary devices–loaves of pitch wrapped in dry bark—intended to burn out the Americans. Ceremonial gear was also collected. To avoid cooking fires, the fighters were likely supplied with dried foods.

Astonishingly, Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens, whose aggressive treaty making and violent attacks on native villages had provoked the war, showed up on the 25th in the steamer Active, traveling from Victoria to Olympia. When worried settlers warned him that they anticipated an Indian attack, he breezily dismissed their concerns saying New York and San Francisco were in greater danger of an attack than Seattle. And then he left.

The attack was well planned. Aware that the period of enlistment for American volunteers manning a fort near the southern outlet of Lake Washington would expire on the 25th, and knowing the American penchant for going home no matter what before their pay period ended, the attacking force began their move across the lake after the volunteers left early on the 22nd. The volunteers were followed by a Duwamish Chief they named Tecumseh and about 125 of his people living at the southern outlet of the lake. When the Indians arrived in town on the 25th, flustered officials directed them to the southwestern point of an island, today’s Pioneer Square area, which was the locus of its commercial buildings and largely separated from the mainland by a lagoon.

Early the next morning, knowing what was going to happen, Tecumseh’s people and others on the island paddled their canoes about 100 yards offshore to watch the show. When one of the sentries noticed this and asked a native woman what was happening, she matter-of-factly answered that the Klickitats were coming to kill all the Americans.

The attacking force was led by several war leaders, among whom was CLAY cum, A Yakima-Duwamish man living on the river, and another named Yet ti cum. Our chief source of information about the native force comes from testimony given during a Court Martial of accused attackers held by U. S. Army officers at Olympia in May of that year. Owhy does not appear to have participated in the attack, nor did the famous Nisqually war leader, Leschi, although Americans believed Leschi did. Early Seattle residents were to name a waterfront park where the force landed for Leschi, but no trial witnesses said they recognized Leschi there. Two witnesses — Chief Seattle’s half-brother Curley, and Old Mose, a resident of the village of Ji Ji LAH letch, “Little Crossing Place,” the native village on Elliott Bay renamed Seattle by settlers — observed events on the lake and relayed information downriver.

As it happened Decatur had been repaired, re-armed and moved offshore in December, eliminating the chance upon which native fighters had banked. Settlers had also built a blockhouse in town, and Decatur’s marines were stationed ashore with a howitzer. Firearms were distributed to settlers and the ship put on alert.

Nevertheless, on the 25th the attacking force crossed the portage trail to Elliott Bay, and by early morning had taken up positions in the dense forest reaching from today’s Second Avenue to the lake. Many approached from under the cover of slash and debris left over from logging near-shore trees and occupied a longhouse on the southern end of the lagoon.

By then, Curley and others had alerted Captain Gansevoort on board Decatur, who fired an exploding shell into the longhouse, blowing it to smithereens. At that, the attacking force gave a mighty yell and commenced firing. The battle roared on all day.

Despite heavy fire, attackers gradually moved north in good order to where vegetation-choked gullies provided approaches to the shore. From these northern points several charges were made on the town but were driven back. During one attack, CLAY cum, painted and dressed in ceremonial garb, braved fire running a zig-zag descent while chanting while singing his warrior song. For his trouble, a bullet trimmed a shock of his hair.

Unable to overrun the town, the attacking force retired at the end of the day, setting outlying buildings aflame as well as virtually all settler homes and farms in King County. Two Americans were killed in the battle, and native fighters carried an unknown number of dead and wounded from the firing line. On the 29th, a much-chagrined Stevens returned to Seattle, begging settlers not to abandon the town “…else ten thousand men could not subdue the Indians.”

Native fighters occupied the fort near the Lake Washington outlet that had been abandoned by volunteers and occupied everything beyond the town until army regulars carried out forays in April. About 10 percent of settlers died in the Yakima War. Many more fled, and the economy was wrecked. The settler population did not regain its pre-war level for another decade.

Historically the Battle of Seattle has been treated as an oddity: an engagement the Indians were bound to lose. In fact, it was a major setback for the settlers. And historians have largely ignored the crucial role played by the Duwamish and Chief Seattle.

Chief Seattle had invited Americans to settle among his people and had single-mindedly aided and supported them. Tecumseh was one of only three Duwamish headmen out of 22 approved by Territorial officials that attended the Point Elliott Council in December, 1855 and signed the Treaty with Seattle. Many others remained unconvinced about the Americans’ motives and trustworthiness.

Besides his brother Curley and Old Mose, Seattle had others stationed around Elliott Bay and Lake Washington providing him with information leading up to the attack. Cooperating with Seattle, Curley removed his people from the Lake, and on the day of the attack made sure they stayed offshore and out of the fight. If the Duwamish had joined the attack and rushed the town that morning, forcing an unwilling Gansevoort to fire into its buildings, the attack may very well have succeeded, even without capturing the ship’s stores. The national ramifications of a west coast town captured even briefly by a native force can scarcely be imagined. And armed with supplies captured in town, the capture may not have been brief.

But even in retreat from the Seattle warfare, the native force brought about a strategic pause in settlement, enough time to deepen connections with Americans and Natives. As a result, the city is more associated with a native presence than many realize. As Coll Thrush writes in Native Seattle: Histories From The Crossing Over Place, “Every American city is built on Indian land, but few advertise it like Seattle.”

Now the city has a chance to cooperate with the modern Duwamish Tribe to repay its historical debt.

For instance, what might be found if a survey and search is made of the area in and around Leschi Elementary School and Leschi Park? The area has certainly been disturbed by a century and a half of development, but even in New York and London, important discoveries centuries old continue to be made. We know children were present at the assembly site, and the activity of between 50 and 100 armed men, joined by supporting women and families would have left evidence. Magnetic and gravimetric scans should reveal metal implements left behind or captured and brought to the site by the retreating fighters. Evidence that these remnants might provide could lead to archaeological investigations at promising sites. We know that many of the settlers’ livestock ended up being roasted and consumed at post-battle camps. This was a major event in Seattle’s past and it will have left a considerable footprint.

There has been no effort to educate the public about what took place in this battle. School district construction at the school site, if carefully done, could provide an unparalleled opportunity for civic education about this crucial event. It should be the City’s responsibility to honor all its people, especially the Duwamish, so it bears the greatest burden to safeguard the site and make its findings publicly known.

The city is deeply implicated in the historic injustice done to the Duwamish by refusing to allow land in or near its ancestral home to be reserved for them. City residents succeeded in making the Duwamish landless, and, as a legal result, unrecognized by the federal government, even though they were the first signatories to the Treaty of Point Elliott, and their Duwamish Chief, Seattle was the primary native spokesman at the treaty council. It has traduced their culture, driven them from their homes, and cravenly refused to support the Tribe’s effort to gain federal recognition.

These willful deeds and omissions constitute the city’s original sin. Helping restore this extraordinary site to public awareness and giving real support to the tribe that saved the town from destruction at its own cost offers Seattle an opportunity for expiation.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for this enlightening article and for paying tribute to the Duwamish, calling for healing and righting the craven wrongs of the white settlers, the regional governance and the federal authority. I am glad to see that here on Post Alley.

Lord knows there is an endless stream of right actions needed.

Is the fort you refer to Fort Dent?

Wonderful story, hidden history, an appeal for at least moral restitution. Thank you David!

The story and the ensuing collapse of the Seattle economy underscores how fragile Seattle was in its first 40 years, and what an economic colony it was to San Francisco. The city didn’t really tain traction until the arrival of the railroads in the 1890s. The story also tells the heartbreaking tale of how we missed creating a multi-racial society, as happened in Spanish Americas. The war depicted here was a fatal blow to those hopes.

clay cum and yet ti cum????……who invented this story? mother goose??….