In the necrology of the demise of American media, one aspect has been overlooked, namely the terminal illnesses of alternative weeklies. A recent story in The Daily Beast ($) looked at fatalities and some survival struggles. The article includes a focus on Seattle’s business-smart, (once) weekly, The Stranger, which was depicted as wrestling with an identity crisis.

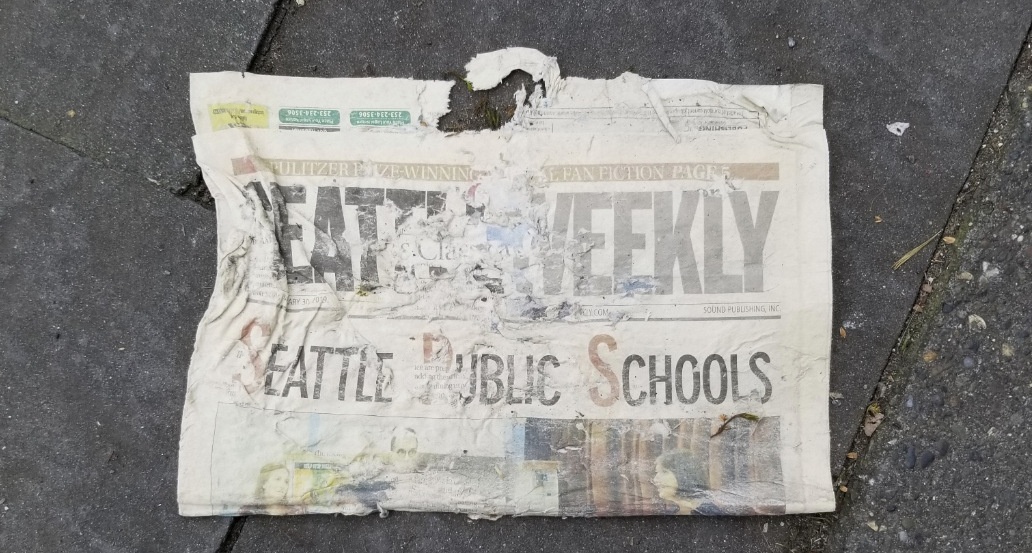

I was part of the upsurge of these papers, which emerged in many cities in the 1970s, displacing the anti-war underground weeklies of the 1960s. Seattle Weekly, which I and Darrell Oldham helped to found (in 1976) and ran for 21 years, thrived for a few decades, sold itself to clumsy owners, and then faded to dark. The loss of these “alties” has been largely unlamented. Only a few survivors (Willamette Week in Portland, the Austin Chronicle) still have the staffs to do serious reporting.

What viruses killed off this segment? Shifting economics with the internet hollowed out many of the traditional income streams for newspapers. Then came more fatal blows with 2007 Great Recession. And then arrived the pandemic, a lethal development since most of these weeklies were sustained by entertainment advertising (and ticket tie-ins), and that economic sector shut down. (The mainstay advertising now is marijuana.) As mainstream media have hired young writers and moved left, the distinctive advantages of the weeklies have faded. As with most other newspapers, classified ads have fled to Craig’s List and display advertising migrated to Google and Facebook.

Beginning in the 1990s, some of the stronger publishers (notably the Village Voice in New York and The New Times in Phoenix and Creative Loafing in Atlanta) perceived that founding owners (like me) were tiring of all the effort and likely to sell. They set about buying up alt weeklies on the theory that there would be efficiencies of scale. But these acquiring companies were over-leveraged and under-managed, so the era of consolidation weakened the new chains. Seattle Weekly was sold to Village Voice in 1997 (a regrettable transaction). Nearly all Seattle media are now owned by out-of-town companies, the exceptions being The Seattle Times, The Stranger, Post Alley, Geekwire, and our public broadcasters.

The publications that survived usually had one or two advantages. One was to be in a relatively small city, where a small newsroom could compete well with the ever-smaller daily (The Inlander in Spokane is a good example). One other advantage was to develop a second line of revenue, such as The Stranger’s getting into the ticket business, promoting music events (Austin and Portland), and hosting other lucrative events such as the Stranger’s Hump Fest for amateur porn.

We tried two diversification ploys at Seattle Weekly. One was to start a suburban counterpart, Eastsideweek, in 1990, which added significant free circulation for advertisers (Seattle Weekly then still being paid circulation) and was edited inspiringly by Knute Berger, now happily installed at Crosscut.com. Eastsideweek was killed off by the Village Voice ownership in 1998, earning my eulogy.

The other diversification was into book publishing, Sasquatch Books. The books were fed by the cash cow of The Best Places guidebook series and were spun off to local owners in 1996. It’s now a leading Northwest publisher, owned by Penguin Random House. In a sense, The Weekly’s company was a familiar roller coaster: a growing company outpacing its capitalization, juggling idealism in a tough and crowded market, and a board awkwardly transitioning from the idealistic founding generation.

Looking back, I can see that there were always two kinds of city weeklies. Seattle Weekly was part of the high-minded, city weekly formula, appealing to young professionals in their 30s and 40s on an upward path professionally, but fondly recalling the rebellions of their college years. The advantage to advertisers was a defined market with money to spend, lots of women readers, and cheap advertising rates (newsprint compared to the glossies).

The other formula was to appeal to a youth market of mostly men in their late 20s, wondering how to get a date, where to go this weekend, and clinging to a cynical radicalism that Dad hated. (Very much The Stranger’s niche.) These upstart “alternative alternatives” were mostly killed off or stunted by the first-to-market weeklies, though not in Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, where crowded markets mostly spelled eventual doom for both contenders. (To be sure The Stranger is still very much alive as a website, though its print edition is suspended and it shifted to fortnightly publication.) The problem with the youth market was that there was not a new ’60s generation to replenish it, and the dailies moved in with better listings and weekend entertainment sections and young (inexpensive) writers. Mostly, the heady moment of alternative/urbanist/radical culture which gave birth to city weeklies in almost all large cities, couldn’t survive economic downturns, social media, and the fading of the 1960s.

It was certainly fun while it lasted. Some very good papers were published, notably Chicago Reader, Maine Times, D.C. CityPaper, East Bay Express, LA Weekly, and Boston’s The Real Paper. Some, like Seattle Weekly and particularly in the northern states, were about building a better, more sophisticated city. Others, particularly those in the Phoenix New Times Sunbelt chain and some venerable ones (Bay Guardian, Village Voice), specialized in take-no-prisoner exposes of corrupt power structures.

The alties didn’t last, in part because they were built on print-economics and late to the digital game. Most of them managed to stay competitive by innovations (classified personals, phone personals, smart — not boosterish — listings), but these ideas were easily adopted by local dailies or low-barrier-entry competitors. I still think the switch to free circulation (Seattle Weekly being one of the last to switch in 1994) diluted the brand. Going free as all of us did also missed the next-wave revenue from digital subscriptions and member-supported nonprofits — now the mainstays for failing dailies and Crosscut-like newbies.

One of the guiding axioms for me in those 21 years at The Weekly was an old magazine maxim: edit the product to readers who want to feel 10 years younger. Media are, for advertisers as well, an elixir of youth. And so, I’d say this failed experiment in alternative weeklies kept alive and deepened the eternal American and big-city longing for youthful tumult, libations, and subverting the oppressor. My 150 fellow publishers and I did our bit to kindle that flame. Seattle Weekly may have perished (except for the archives), but Seattle has become very much an altie-city.

.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

David, your business model was GREAT and it worked for a long time.The Weekly always had something to say (read) – not just a place for Personals.

David, very insightful based on your personal experience (always dedicated to quality news publishing).

Bainbridge Island, 2 news weeklies, plus Kitsap County. Essential to having sense of community.

Bring back Argus!

I would question your description of the Stranger as appealing “to a youth market of mostly men in their late 20s, wondering how to get a date, where to go this weekend, and clinging to a cynical radicalism that Dad hated.” Particularly the “cynical radicalism” claim, which doesn’t really fit any era of the Stranger that I can think of.

In my era of writing for the paper (2002-5) the Stranger was funny, profane, anti-establishment and often contrarian. It didn’t take itself too seriously — unlike the ponderousness of the Weekly, which by the time I got to town was clearly having the life crushed out of it by the weight of its own self-mythologized history — and it was a writers’ paper more than a journalists’ paper, but was also beginning to engage more substantively on the news side. Nowadays the Stranger is much more earnest and activist – one might even call it naive at times — the opposite of cynical. The news content has declined noticeably, due to staff cutbacks and the harder turn towards left advocacy, but it’s not like the Seattle Times produces as much news as it used to either.

It’s clear from reading your analysis/eulogy that these alt weeklies flourished in a time when journalists felt passionately about civic life and speaking truth to power. When I got to « it was fun while it lasted, » I couldn’t help but feel a bit depressed.

We become what we set out to replace.

The Stranger provided a platform to several good writers who went on to better places, but I was often appalled by its sophomoric viciousness dressed up as wit and its thin skin when others disagreed. On topics like the Monorail, if you disagreed, it was off with your head. They were Seattle’s Taliban.

Aside from the revenue problems David discusses, which gutted nearly all the alt-weeklies, the biggest challenge for these papers is covering relevant issues as cities evolve and grow. The Seattle Weekly felt increasingly detached from Seattle after 2004 or so; it was eventually like some uptight hippies and a bottle of NyQuil were having a fireside chat about the Sonics. The issue wasn’t about being progressive or targeting a younger audience or pissing off daddy, either: Look at Joel Connelly, who kept his decidedly moderate reporting on the pulse, stayed in the mix of Seattle’s discourse, and blended his writing with (mostly) relevant anecdotes — for years after Seattle Weekly basically gave up.

Sandeep is right about one thing: The Stranger wasn’t written for men in their 20s. It resonated across demographics, as proven by its influence on elections, where people in their 20s are of little influence. While the ad revenue was still strong and they had enough good writers, The Stranger got into the nitty gritty of urban life and homed in on the most urgent issues of a growing city: housing, transit, homelessness, losing cultural venues, racist police, etc. Also, The Stranger had absolutely brilliant culture critics and it unapologetically promoted the arts. It wrote like people talked. It made downtown real estate lackeys get so mad they still call it the “Taliban.”

So while I agree that the alt-weeklies that remain must diversify their revenue, I think it’s facile to say it’s about writing for a youth audience or that the youth audience of yore isn’t replenishing. There will always be fresh crops of new readers — and old ones who will keep reading — if they write about their cities as they actually, currently exist, not like nostalgic keepsakes.