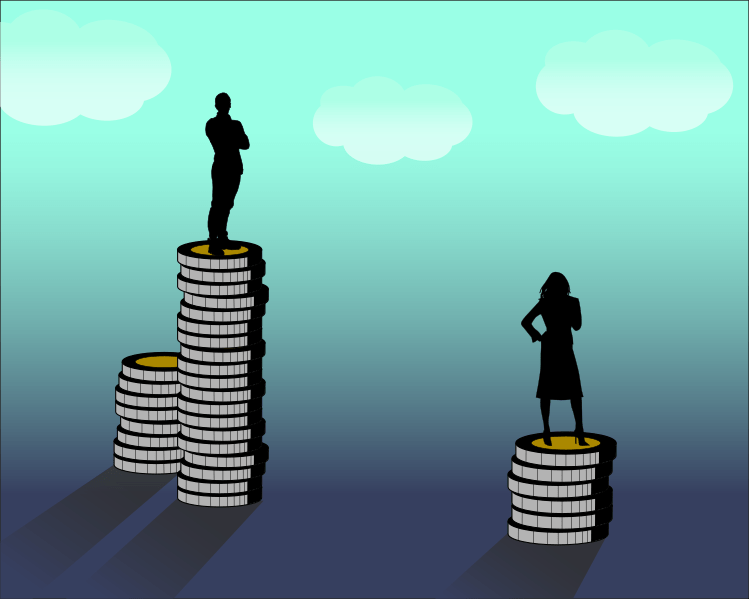

Women across the country still take home less pay than men despite decades of work to close the gender pay gap, and experts report that the pandemic’s toll on working women may undermine what small gains have been achieved.

When Rep. Tana Senn, (D-Mercer Island), finally won passage of the Washington Equal Pay Opportunity Act after four tries, she looked forward to watching women use its new tools to narrow the pay gap. The 2018 law addressed issues like pay secrecy, but it couldn’t foresee a pandemic forcing many working mothers to cut back or quit when their child care disappeared.

“We’re in a little bit of a new frontier of whack-a-mole. What is the most recent or greatest cause of women not having equal pay? We whacked the mole of pay secrecy, but now what we’re seeing as a huge issue is access to child care,” says Senn. “Women say great, now I’m going to get equal pay, but only if I can actually work all those hours to make it equal, but I can’t because I don’t have child care. And by the way, that is falling on me more as women than on the men.”

Advocates point to research showing that women still shoulder most of the unpaid labor to keep families going – the shopping, cooking, cleaning and other chores that contribute to a housework gender gap. The National Conference of State Legislatures in a February 12 report on the status of the gender pay gap said McKinsey Global Institute, along with other sources had found that “another reason for high female job losses is because women do about 75% of existing unpaid work and may have been overly burdened by increasing child care needs due to the pandemic.”

“Women are like, I’m done, I just can’t do it anymore, I’m out,” says Senn. “We know that is costing Washington state alone $13 billion a year of foregone wages by working parents because of the lack of child care.”

According to Child Care Aware of Washington, last year up to 24% of the state’s licensed child care programs were closed and currently 14% licensed providers are closed, some of them permanently.

The Fair Start for Kids bill introduced by Senn and Sen. Claire Wilson, D-Auburn, seeks to expand the availability of child care and make it more affordable for families. Senn says she is optimistic about the bill moving forward and is “feeling quite confident” that the legislature is willing to invest in child care.

The dire impact of the pandemic on working women also is central to COVID relief efforts by the Biden Administration. In a recent column for the Washington Post, Vice President Kamala Harris called the mass exodus of women from the workforce “a national emergency which demands a national solution.” She wrote that, “Job loss, small business closings and a lack of child care have created a perfect storm for women workers…Before the pandemic, working mothers already had it tough. Now, it seems nearly impossible.”

In a February 18 video call with women leaders, Harris pointed out that 2.5 million women have left the work force since the beginning of the pandemic compared to 1.8 million men. She said the Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan would help families recover by providing $3,000 in tax credits for each child and a $40 billion investment in child care assistance.

Recent statistics underscore Harris’s comments. In December, employers reported the loss of 140,000 jobs. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, all those jobs – 100 percent — were held by women. In January, the pandemic forced another 275,000 women out of the U.S. labor force. As Fortune reported, “Working women have now lost more than three decades of labor force gains in less than a year.”

“Not only are women not getting paid equal to men, the child care system has failed them, the work places have failed them,” says Rep. Liz Berry, D-Seattle, a mother of two young children who worked from home while running her first campaign for office during the pandemic. “I have a great support network, and I’m so privileged, but I still feel like I’m drowning every single day.”

Berry signed onto Senn’s bill and also is working on other measures to help working families like expanding the state’s Paid Family and Medical Leave Act.

The annual gender wage gap in Washington is $12,960, according to the National Partnership for Women and Families which tracks the gap across all states. Washington was considered cutting edge when it passed an equal pay law in 1943, two decades before Congress passed the federal equal pay act. The first update to Washington’s law took another 75 years, and the state is now among 18 plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico that have enacted laws against pay secrecy.

It’s unclear how well the new state laws along with federal measures like the 2009 Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act were working even before the pandemic threw a major wrench into the works. As the National Conference of State Legislatures noted in a report this month: “Prior to the pandemic, women in the United States earned just 89 cents for every dollar made by a man.” The report said the rate has “remained relatively stubborn over the last 15 years” and the gap for non-white women remains even more intransigent. “According to data from 2020, among women who hold full-time, year-round jobs in the US, Black women are typically paid 63 cents, Native American women 60 cents, Latinas 55 cents and Asian American women 87 cents for every dollar paid to a white male working in a similar position.”

While the needle may not have moved much, advocates like Senn say pay transparency will make a difference. How can you know if you are being paid appropriately if you don’t know how much others are paid for the same work? Senn’s bill allowed for discussion of wages between employees, banned retaliation against workers who discuss their pay or ask for equal pay and took steps to provide equal opportunity for job advancement between the genders.

When Gov. Inslee signed into law the Equal Pay Opportunity Act, he said: “There is still a lot of work remaining to achieve true pay and opportunity equity for women in the workforce. This bill tears away the ability of companies to shroud salary and promotion decisions in secrecy. This makes it possible for employees to discuss how those decisions are being made without fear of retaliation.”

The push for greater pay transparency may finally get a boost by Congress now that the Democrats control both houses. After years of getting nowhere with the Paycheck Fairness Act, Sen. Patty Murray reintroduced it last month on the 12th anniversary of signing into law the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. The measure would prohibit employers from relying on salary history to set pay when hiring, protect employees from retaliation for discussing their wages, and require employers to report race and gender wage gaps to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

“As workers across the country struggle to make ends meet amid this economic crisis, women cannot afford to wait any longer to get equal pay,” Murray said in a release.

A recent report by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research compared a 2010 survey of pay transparency policies with a 2018 survey, concluding that, “existing legislative changes have not been sufficient to rid workplaces of rules against discussing pay.”

The report went on to note that “while these laws protect workers from retaliation for discussing wages and salaries, they do not mandate transparency practices by the employers and they leave the responsibility for finding out about pay to the individual (women) workers.”

Since Washington’s law on pay secrecy took effect in June of 2018, the Department of Labor and Industry says it has received a relatively low number of complaints related to violations of the law: a total of 37 complaints alleging violations of open wage discussion protections. In an email replying to questions from Post Alley, a staffer said, “we have found employers are not aware of this new protection or have not updated their employment policies.”

L&I told Post Alley that it is in the process of expanding outreach efforts to include free employer consultations about the impact of the 2018 law on their organizations. The department also plans by the end of February to make available on its website additional tools to help employers and employees address the gender pay gap, including a self-evaluation for employers to conduct of their organization to confirm compliance and a tool that workers can use to determine whether their organization is paying similarly employed employees differently.

Senn says she was encouraged to hear that Washington law firms and accounting businesses were reaching out to their clients to alert them to requirements of the 2018 law. She’s also heartened by anecdotal accounts of women who were able to push back and get a raise. But she notes that to act on the law, “someone has to complain about it.” The burden remains on the women.

Lilly Ledbetter only found out she had been paid less than men doing the same job when someone left a note in her work locker. By then she had missed the deadline for filing an equal pay complaint. I met with her when she came to Washington, D.C., to testify for passage of the law to fix that time requirement. She was passionate about speaking her truth. The bill bearing her name passed and was the first law President Obama signed after taking office in 2009. But it didn’t change things for Lilly Ledbetter. Her pension was based on those years of unequal lower pay.

All the women cutting work hours or leaving the workforce because of the pandemic-fueled child care crisis aren’t just doing without those funds now. The time out of the workforce will impact their future earnings and retirement savings. “When women don’t make the same amount as men,” says Rep. Senn, “it leads to women in poverty when they are older, and they live longer.”

As Harris said, women today are caught in a perfect storm, and swift federal and state action to expand child care and enforce paycheck fairness are urgently needed.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great work documenting this dismal situation. We had vast gender disparities before the pandemic and they have grown worse now. Much can be done to close the gender gap with legislation, if only these laws are approved. Write, email and harangue your representatives today. Ask what they’re doing to give women a fighting chance at fairness. And then thanks to the Patty Murrays and Tana Senns.|

Yes, and when hopefully the bills expanding child care and family leave are passed, what kind of oversight is needed to assure that they fulfill their goals?