When I gave a presentation recently at the Chehalis Public Library on my book, “Chief Seattle,” the young librarian introduced me in the Native American language that the old chief spoke. Non-Indian, the librarian had taken classes so her audience could hear the sound and cadences of what he said more than a century ago. I was impressed.

Chief Seattle’s language belonged to the great Salish family of languages spoken from Montana to the Pacific Ocean and from Oregon to central British Columbia. A sub-grouping, the Coast Salish languages, were spoken on coastal and inland waters. A further sub-division spoken in the Puget Sound region is called Puget Salish. Starting in the north near Bellingham, it was the language of the Samish, Swinomish, Skagit, Stillaguamish, Sauk-Suiattle, Snohomish, Skykomish, Snoqualmie, Suquamish, Duwamish, Puyallup, Steilacoom, and Nisqually peoples. With the exception of Suquamish, these are river names and, as “every river had its people,” each appears to have had its own dialect.

On the Tulalip Reservation near Everett, the language is identified as Lushootseed. Other names for it are Twulshootseed and Whuljootseed, the latter from Whulj, “Saltwater,” and –ootseed-, “mouth,” meaning, “Saltwater speech” or “Saltwater Language.”

Very few Lushootseed speakers survive, and the language is regarded as critically endangered. The next stage of decline is dormancy, a so-called “sleeping language” that has no proficient speakers but is still important to a particular ethnic community. Extinction comes when an ethnic community dies out or no longer uses its language. To keep Lushootseed from becoming dormant or extinct, efforts are being made to revitalize it.

The Lushootseed Department of the Tulalip Tribes offers classes in Lushootseed, and a Lushootseed “Phrase of the Week” appears on the Tulalip website. The Puyallup Tribal Language Program offers Twulshootseed lessons. Pacific Lutheran University’s Language and Literatures Department offers classes in southern Lushootseed. The Lushootseed Language Institute at UW Tacoma offers classes as does the College of Arts and Sciences at UW Seattle. The Wah He Lut School north of Olympia provides a Native American cultures and language curriculum for classes 1 through 8. All this has happened since the 1970s.

The English use of the name Salish goes back to the work of Italian philologist Gregorio Mengarini, S. J., one of Jesuit Pierre Jean DeSmet’s missionary band that founded the 1841 St. Mary Mission in western Montana among people western traders called Flatheads. The Jesuits had always made music part of evangelization, and Mengarini had been chosen by the Jesuit Superior General because of his strong voice and musical skill. He also had such a good ear for language that it was said if you heard him in a group of native speakers but did not see him, you could not tell which voice was non-native.

Confusingly, the Flatheads were so named because they did NOT flatten their heads, that is, compress their infants’ growing skulls to make them oblong. They called themselves Say-LEESH—Salish—meaning “The People,” and the Jesuits set about learning their language to write prayers and songs. Mengarini wrote a Salish grammar still used today and he compiled vocabularies.

As ethnographers expanded their work, languages related to Salish were organized into the Salish language family. But the word came to identify groups speaking Salish languages who did not identify themselves as Salish. In our area, there is a mindless tendency among non-Indians, even those who should know better like museologists, to identify Puget Sound groups as Salish Indians or concoct odd terms like the Salish Sea. This happens despite the obvious fact that the groups have their own names and the only Salish Sea is Montana’s beautiful Flathead Lake.

This misnomer is largely the result of heedless marketing or efforts to alter history for financial gain. A non-native calling a person of Duwamish ancestry Salish is engaging in “white speaking”– tantamount to calling English speakers Germans because they speak a Germanic language.

Living languages require good dictionaries. For oral languages with few fluent speakers the creation of a dictionary often requires decades of careful research and close collaboration with surviving speakers. The 19th century lawyer and philologist George Gibbs wrote A Dictionary of the Nisqualli, the first Lushootseed-English dictionary, WHICH was published in 1877, four years after his death. The name, given by traders to native people near Fort Nisqually. is made up of the prefix Nees or Bees, “where there is,” and the root SKWAH lee, “grass,” that identified Nisqually Prairie. It appears in dxw sqwali ahbsh, the name of the modern Nisqualli Tribe, the suffix ahbsh meaning “people of.” Gibbs settled near the town of Steilacoom in 1854 where he hired a Nisqually man, whose English name was Jack Cook, to tend his fields. He was probably Gibbs’ primary informant, giving the work its southern Lushootseed slant.

Gibbs distinguished between Nisqually and a dialect spoken further north he identified as Skagit, a division reflected today in the division between southern and northern Lushootseed dialects located near the Snohomish / King County line. The Tulalip language website lists the Skagit, Swinomish, Sauk-Suiattle, Stillaguamish, and neighboring peoples as speakers of northern Lushootseed and the Snoqualmie, Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Nisqually, Squaxin Island, Suquamish, and neighboring groups as southern Lushootseed speakers. The dialect spoken at Tulalip is identified as Snohomish Lushootseed, a variant that shares words from both dialects. Politics plays a role in selecting these groups–all recognized tribes–ignoring the Duwamish and Steilacoom that are not.

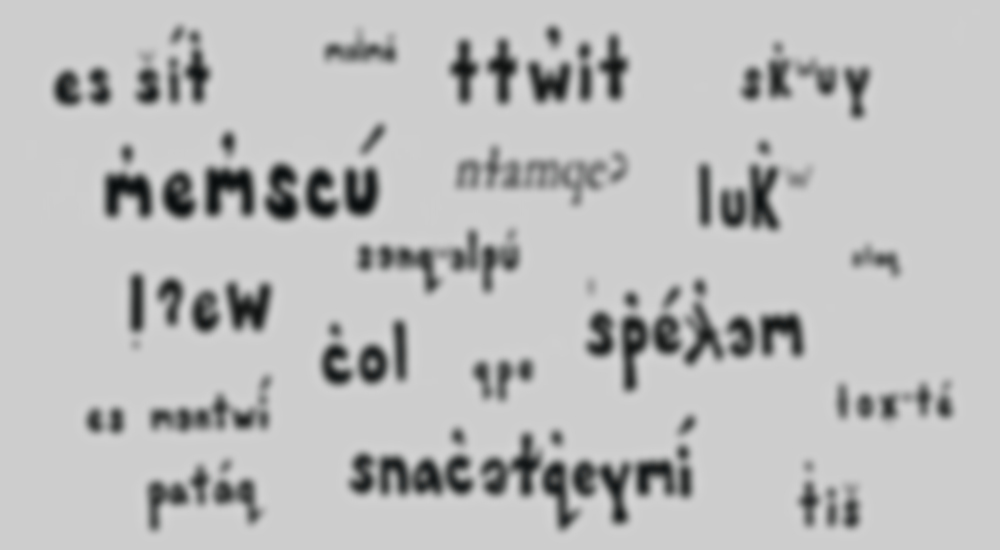

The most recent Lushootseed Dictionary, edited by Thom Hess and written by him, Dawn Bates, and Vi Hilbert, was first published in 1976 and revised in 1994. It provides a unique alphabet to express unfamiliar sounds in pronunciation. Lushootseed has about 40 consonants and a range of vowel sounds. Like most western alphabets it is arranged with a-b-c sounds at the beginning and x-y-z sounds at the end. Head words, those with entries, are listed according to the first letter of their roots, not of the word itself which may start with a prefix. These head words are listed separately. A dictionary should provide all meanings of words in different contexts and give examples of usage. The Hess dictionary does not include native place names although over 700 of these exist. Nor does it standardize the spellings of roots which, with affixes, make up Lushootseed words. But it is the workhorse of Lushootseed education.

Can a sleeping language live if the world it described no longer exists? The same could be asked of English since there are not many shaggy ruffians wandering in sheepskins muttering in Old Norse, Frisian, or Old English, not even in Ballard. Our language evolved with huge admixtures of Gaelic, Danish, and Norman French with Greek and Latin roots and hordes of loan words from a colonizing past that enriched it. Hebrew survived among rabbis and scholars until the late 1900s when its revitalization became part of the Zionist movement and the creation of the State of Israel.

The same happened with Gaelic during the Irish literary revival in the late 1900s and independence in the 20th century. In the early 2000s, barely 30 native Hawaiian speakers survived. Today, with the language protected by law and encouraged by schools, perhaps 18,000 are conversationally fluent at home. It underscores the truth that the best venue for teaching a language is the family setting.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, northwestern native languages added many words to English. It spawned a trade patois, Chinook Jargon, that shows up in town names like Enetai “Across the water,” Whatcom, “waterfall”; also in ferry names: Tilikum, “friend,” Issaquah, “confluence”; and resorts like Hyak, “Hurry,” at Snoqualmie Pass and Semiamoo, a group name, near the Canadian border. Native words name Washington’s rivers, cities (Seattle, Tacoma, Spokane) and parks like Licton, “Colored,” in Seattle that describes its reddish spring water. We dig for Geoducks—Gwiduk, “He has hairs on his penis,” horse clams, Haach, “good eating,” fish for sockeye–Suk kegh, “red fish,” or pick berries of salal, a word coined by Lewis and Clark and of obscure origin. Transfer did not happen all one way.

Dictionaries of endangered languages are helped by written texts. A remarkable example of this is the work of jessie little doe baird (her lower case spelling reflects the ethic of E. E. Cummings) to revitalize Wopana’ak (Wampanoag), the language spoken by the Wopona’ak people in southern New England at the time of Plymouth Plantation founded in 1620. A full 90 percent of the Wopana’ak had died from epidemics by the time the Pilgrims landed. Most of the rest were killed in wars or driven out by English colonists, and the language ceased being spoken in the mid-1800s.

But Puritan missionary John Eliot, seeking to convert native people by learning their language, created an alphabet and published the first Bible in New England—written in Wapona’ak. Converts became literate and wrote letters and deeds in the language, leaving a corpus of material written phonetically in grammatical and comprehensible Wopana’ak. Although the language disappeared, a Wopona’ak prophecy said that the people would not be able to keep their language, but a group leaving New England would take with them a pipe containing the language’s spirit, and one day a woman would be able to welcome the language home.

A resident of Mashpee, Massachusetts, on lower Cape Cod, baird had three successive dreams in which people who looked familiar spoke words she could not understand. These happened to be street names on Cape Cod, and her interest in the language brought her closer to Wopona’ak communities in Mashpee, on Martha’s Vineyard and to the academic community at MIT. Studying Wopana’ak texts, she earned a masters in linguistics and determined to revive the language. She wrote a 10,000-word Wopana’ak-English dictionary. Today, from a base of zero speakers, more than a score are conversationally fluent, and 50 attended a recent total immersion program.

Early in the 20th century, anthropologists Herman Haeberlin, Thomas Talbott Waterman, and linguist John Peabody Harrington transcribed Lushootseed interviews and myths, and more recently anthropologist Warren Snyder and Upper Skagit speaker Vi Hilbert made recordings of the language with Bates, Hess and others. These provided the underpinnings of the Lushootseed-English dictionary.

Another Puget Salish language, Twana, spoken on Hood Canal, has benefited from similar work. Ethnographic material collected by 19th century missionary Myron Eells and the solid linguistic work of anthropologist William Elmendorf and others in the mid-20th century provided large collections of texts.

Since the 1970s another anthropologist, Dr. Nile Thompson, a linguist, has been studying the Twana language and composing an extraordinary dictionary, perhaps the greatest of any Puget Salish Language. Thompson points out that previous Puget Salish dictionaries that are primarily linguistic documents tend not to serve native communities or researchers outside the field of linguistics, people who want to know more about a language’s role in a culture. To fill out entries, Thompson draws upon wider ethnographic studies that enlarge the understanding of the word.

For example, in the Lushootseed-English dictionary, the headword (a word with an entry) for a supernatural being is written phonemically for pronunciation and briefly described. In his Twana dictionary, Thompson adds ethnographic information about the being in different contexts from other Puget Salish sources including different pronunciations and usage. The headword for crow in the Lushootseed-English dictionary is equally brief, Ka’ka, but Thompson adds no less than 17 other ethnographic sources describing crows, the mythological being Crow, and baskets and other beings associated with crows. Many provide different pronunciations and examples of usage, and even this was in a preliminary version.

The result is wondrous. Not only do we learn more about the word and its use, but about the world it which it lived and lives. The finished work will be monumental, but Thompson’s decades of research hung on grant requests and the vagaries of tribal politics. Another aspect of his work is finding best ways to effectively teach the language, another rocky road.

In the New World, there is one place where a native language thrives. In Paraguay 60 percent of if its people speak Paraguayan Guarani, and 70 percent of these are non-native. Guarani belongs to the Tupi language family with speakers from French Guiana to Uruguay, from the Andes to the Atlantic. While governors made Spanish the official language, most natives refused to learn it so that governors had to learn Guarani. With the collapse of the Jesuit reducciones and the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata, the region entered a period of extended chaos in which at least 60 percent of its population died in wars during the 1840s and ‘50s. Paraguay’s history resembles the Native American experience in the U.S. with its brutal genocides and organized suppression of native cultures and languages, but, ironically, chaotic dysfunction in Paraguay limited language suppression, and Guarani language loyalty remains strong. Enriched by loanwords from Spanish, Portuguese, German, English and other native languages, it has evolved like any modern language. Indeed, its success threatens other local native languages less well documented and spoken by smaller groups.

What is the prognosis for Lushootseed? In truth, native language survival in Washington remains problematic. Not many teachers have been taught the dynamics of how to teach a language. Family influence in tribal politics sometimes interferes when qualified people are dismissed so kin can get jobs. Likewise, in academia, chasing grants rather than solid research becomes a guiding principle, and poor programs are praised to keep the money flowing. Museum staff with little historical and no linguistic background create exhibits that generate ignorance rather than knowledge. But these shortcomings are hardly unique to language programs, and one need only reflect on where we are to gauge how far we have come.

Did I ever imagine that in my lifetime I would see scores of native canoes travelling Puget Sound and pulled up on beaches in joyous celebrations? Nor am I surprised when I visit the Tulalip Cultural Center to give a presentation and a young greeter welcomes me with a beautiful woven blanket and a sonorous Lushootseed introduction. And at the end I often ask the audience how I did speaking native words and phrases? I could not be happier to hear a very kind person tell me with a toss of her head, “Oh–not too bad.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Fascinating, and deeply informative. But I doubt Paraguay is the only place in the Americas where native language thrives. Various Maya dialects and other ancestral tongues are still the first, sometimes only languages for hundreds of thousands of people in Central America and Mexico. But they haven’t spread more widely, as it seems Guarani has.

BTW, I sat in on a Lushootseed class at the Duwamish tribal longhouse some years back; teacher and students both seemed very much engaged.