Pre-Covid, the model for many American theater companies in the provinces, such as Seattle has been to run a play for four weeks or more; to import most of the actors for a few weeks; and to build up a large support infrastructure to manage the place and bring in the donations and audiences. Post-Covid, a new/old model may be possible, as sketched out in this article by veteran theater administrator Jim Warren.

Put simply, Warren recommends these three steps. Build a mostly local company of actors, with fewer imports. Second, to give actors more regular work (40 hours a week with benefits), have them do more of the administrative chores, just like an energized startup. Third, revive the repertory idea, where the same company of actors performs plays in nightly rotation. A similar model might work for opera, as The Atlanta Opera is shifting to (including performances in circus tents). The variant for symphonies is to use the players in various configurations (symphony, chamber orchestra, chamber music, recitals) and venues, as the Berlin Philharmonic has done for years.

The Seattle Repertory Theater (as the name recalls) once deployed a repertory method. It commenced in 1963, right after the Seattle World’s Fair, when the repertory idea was the hot idea for regional, non-commercial theater. A shifting company of resident actors would rotate several plays, night after night. It gave the actors steady work and a great way to learn repertoire. It gave audiences a way to see favorite actors in varied roles. For visitors (as at the Shakespeare Festival in Ashland), the system gave them a way to see a different play each night.

It didn’t continue this way, and “The Rep” is now doing the conventional multi-week runs of one play (sometimes a second one in the smaller theater). Bagley Wright, who spearheaded the early days of the Rep (and for whom the Bagley Wright Theater is named), told me that he discovered one key problem: there wasn’t enough room at the theater (the one now called the Cornish Playhouse and long home to Intiman) to store the sets, which of course have to be struck and stored and a new one installed each night. Lacking storage, in came the expensive moving trucks. The real problem was that Wright grew disenchanted with the creative work of artistic director Stuart Vaughan, a Shakespeare expert with serious prima-donna traits and who founded several other repertory companies.

Of course the new Rep playhouse has a bigger scene shop and storage area, so the scenery aspect seems fixable — not to mention the growing trend of projected scenery. Also, there are other savings from this economic model, such as the paring the cost of auditioning, flying in, and putting up actors from afar. In a repertory company, some actors take on several roles each night, another saving. And these company actors get very good at playing off each others’ cues and strengths. The model also means more steady work for local actors and artists. Worked in Shakespeare’s day pretty well!

On the other hand, repertory companies are significantly more expensive. The biggest repertory theater, Ashland, has a huge budget. Opera companies in Vancouver and Philadelphia and St. Louis who use this model are struggling examples of how difficult this is to pull off.

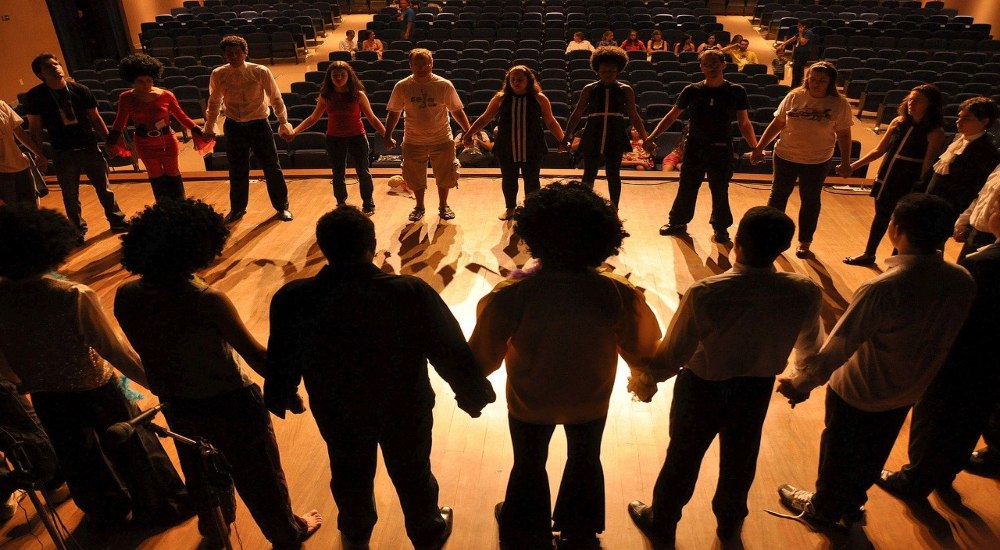

Another benefit is the creation of “the company model,” which pays dividends in fairness and equity and team spirit. Here’s how Jim Warren explains this aspect:

Creating the company model. Putting performers at the center of a theatre’s business model is a new old idea whose time has returned. It simply doesn’t make sense that we pay some folks—from artistic directors to custodial staffs—year round, with most of them working 40 hours per week for a guaranteed, 12-month salary, plus paid vacation, plus sick days, plus paid holidays, plus health insurance, while the artists who create the work that drives our business are “contract workers” or “gig workers,” usually employed as independent contractors for a few months at a pop. In the contracts for most of these folks, we usually don’t include company health insurance (some get it through Actors’ Equity, but not all), nor all of the other benefits listed above that we are required by law to give “regular” full-time employees.

Certainly the business of the arts shifted as business became bigger and more complex, but collaborative models often find that artists are not well suited to manage the administrative tasks, and often these artists become lesser in both roles. So this hybrid model remains quite rare. Even so, positioning artists to the the center of these organizations is a worthy goal.

I somehow doubt that the Rep, which long ago switched to the model of elaborate productions often aimed at heading to Broadway, could make such a desperate revival act. But a new company, a smaller group? Any mini-Medicis out there who might want to underwrite some experiments in this new/old thinking?

Thanks for this David, I believe Donald Byrd makes annual contract commitments to his dancers and so does Olivier Wevers, same dancers in every show and real loyalty and chemistry. I feel at Early Music Seattle we have been pushed into this model, using our local baroque players for all the recording of online shows. It makes me consider why we did not commit to them in a similar way before. Bringing in one touring group after another seems exciting, but with covid stretching out, it’s a way off, and those artists are not in town to become part of the community and develop recognition for the organization. Developing our local talent pool may be long overdue.

I can confirm one point David makes from my own experience. Unless the mores of actors have changed radically in 45 years, hardly any are “well suited to manage the administrative tasks.”

Between 1975 and 1977, the performers and management of the Empty Space Theater agreed to act as a collective, sharing 50% of box-office revenues equally between individuals, voting on repertory and casting, and sharing the scut work of keeping the house clean, manning the phone during office hours, etc.

What happened on stage during this three-year period was an extraordinary flowering of talent and energy bordering on genius. What happened backstage was griping, quarreling, and recrimination, all due to the necessity of taking responsibility for anything other than “the Art.” Even the necessary weekly company meeting to decide essential artistic questions were routinely marked by exhibitions of adolescent pique and and sarcasm, rollings of eyes and under-breathed mutterings. As for clearing the toilet and manning the reservation line–no, I won’t go there.

These defects weren’t the one that ultimately brought down the collective. But they were what made possible its demise. Other bands of artists have made a go of sharing most of the work of making great theater consistently over decades: the San Francisco Mime Troupe, Chicago’s Steppenwolf, New York’s Mabou Mines, to name three: What set them apart was a shared vision of the work which helped keep egos and ambitions in line. At TESA, the only thing holding things together was a passion for performance and having fun. And it wasn’t–it never is–enough.