These last days before the election seem to be pushing the dial from urgent to frantic to completely bonkers — at least if my email in-box is any indication. I do sometimes wonder if, after the election, I’ll get any emails at all — given that the number from candidates and election-related causes seem many days to account for 90%+ of the traffic.

To strike a small blow for calm, let’s think about something else altogether, like poetry and dogs and reading aloud. Some of you will know an especially fine poem by William Stafford, “A Ritual to Read to Each Other.” I won’t quote it all, but you can click on the link to read its five stanzas. And do! Here is the closing stanza:

“For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.”

Reading aloud is something I do a lot of with my grandchildren. As they get older they are of course reading to themselves, or, on occasion, turning the tables and reading to me.

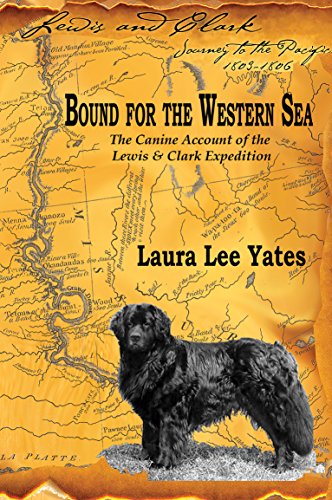

Recently, 9-year-old Colin and I finished a book that is a little offbeat, but which I recommend, especially for dog lovers. Lucy Lee Yates wrote, Bound for the Western Sea: The Canine Account of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The book is narrated by Meriwether Lewis’ dog, Seaman, a Newfoundland. While the book would fall in the genre of historical fiction, it tracks the journals and history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition closely. As such it is a great introduction to this important chapter in American history. And there really was a “Seaman.”

Because of Seaman’s devotion to his master, Lewis is really the focus of the book. And, of course, it is in some respects a tragic tale in that Lewis takes his own life in 1809, five years after his return from the Corps of Discovery. There has been some controversy about the circumstances, including some theories about an assassination. But those have been largely debunked.

At least in Yates’ presentation, Meriwether Lewis is afflicted by depression, though Yates, in keeping within her work’s time frame, never uses that word. Lewis managed to keep depression at bay by taking on big challenges and working at a ferocious pace. But after the famous expedition was behind him he could not keep what Seaman describes as “the black shadow” from engulfing him.

I recognized in Yates’ account of Meriwether Lewis something of myself and my own experience of depression. Lewis had an enormous sense of responsibility for the success of the expedition and the welfare of the members of the Corps (like a pastor you might say). Beyond that he worked feverishly at the collection and documentation of flora and fauna encountered along the way. He kept extensive journals. All his collecting and writing had President Jefferson in view as his first intended audience. It is fair to say that Lewis longed for Jefferson’s approval as one might long for a father’s approval.

It would also be fair to describe Lewis as “driven.” When he didn’t meet his own extraordinarily high expectations, internal voices of recrimination drove him down. After the expedition itself was over he suffered the ironic “grief of success,” of a great goal attained but now over. Would anything else in his life ever compare? Lewis began to self-medicate with alcohol, which seems to have been the beginning of the end.

All the while, Seaman watches Lewis, doing all that he can to protect and comfort the master to whom he is devoted. Through Seaman’s eyes you see the mix of grief, guilt and sense of powerlessness that is often experienced by those who are the survivors of the suicide of a loved one.

To be clear, all of this subplot, while of particular interest for me, is but a part and a small one really of the overall story of the adventure. There’s plenty to keep the mind of 9-year-old thrilled and engaged.

These days we live between pandemic and politics, both generating a thousand rumors and alarms. The times continue to be trying, or as Stafford put it, “The darkness around us is deep.” Times that test our faith.

Seaman the dog, among other things, was religious! He refers often to “The Great Mystery.” Amid the hazards and affections of life, the Great Mystery is a hovering presence and providence that abides, that has its own inscrutable purposes, and endures as an outline of grace beyond the brokenness of life. My own faith in “The Great Mystery,” abides. I pray that yours does as well.

Hang in there, everyone and every dog.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.