Journalists are a competitive lot. We live for getting a scoop. And that often requires access.

This is especially true in the nation’s capital where historically journalists have nurtured special relationships with sources. Remember Ben Bradlee and President Kennedy? Back when face time meant something else, political reporters measured their worth by getting time face to face with key officials in the White House and Congress.

But unlike the days of Bradlee and Kennedy, getting past the army of gatekeepers that surround officials these days is no easy undertaking.

When I was invited in D.C. to several “girls’ night out” dinners, I happily said yes. These gatherings with journalists and officials seemed one way to help build a girls’ network like the boys’ networks that too often excluded us. It’s a lot easier to get a call returned if the chief of staff or the presidential adviser has met you.

A few of these dinners were held at restaurants, but more often we gathered at the homes of journalists like Judy Woodruff and Norah O’Donnell. Each dinner had a guest or guests of honor who were prominent women in government. I remember going to one that feted Tina Tchen when she was Michelle Obama’s chief of staff. It was a prime opportunity to get face time with someone whose help I needed for my magazine’s coverage of the First Lady.

These girls’ night out gatherings recently made news. And not flatteringly. Susan Page of USAToday hosted a 2018 dinner at her home for Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma. Verma used taxpayer money to pay consultant Pamela Stevens to organize the event. Page has said she footed the bill for the dinner herself and did not know Verma was paying Stevens.

Looking back, I now need to ask myself whether any of those dinners I attended were actually set-ups by paid consultants seeking to build their clients’ visibility. And why didn’t I ask that question at the time?

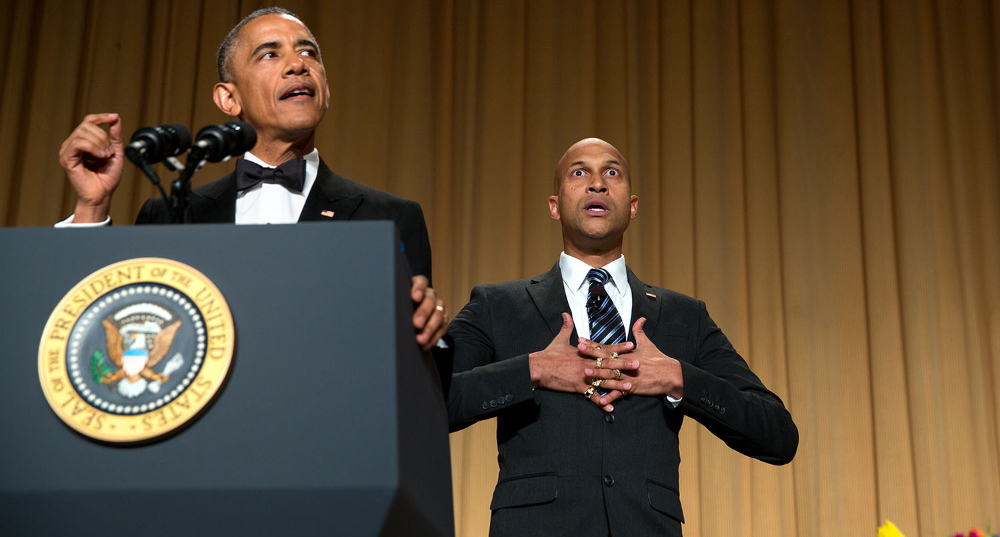

Margaret Sullivan, the Washington Post media columnist, this week wrote critically of those dinners and galas in the nation’s capital where journalists and those they cover mix and mingle. Exhibit A is the White House Correspondents Dinner. Even though the annual extravaganza honored outstanding journalism and awarded scholarships, it became an outsized social scene.

News outlets competed aggressively to snare tickets, and then competed even more aggressively to invite high profile guests to sit with them. The goal was twofold – access and buzz. Reporters wanted to schmooze with government officials and their top aides, those officials and aides wanted to work the press, and everyone wanted their name and pic to pop up on social media.

But what ethical lines are crossed or blurred when journalists and public officials get so cozy? Do reporters hold off asking tough questions of the person they just dined with? This isn’t just an issue in the nation’s capital. When I covered Oregon politics in Salem, elected officials and the journalists who covered them often mingled after hours.

The relationship between reporters and sources is complicated. Each wants something from the other. As Jean Godden recently wrote for Post Alley, these relationships become even more complicated when sources want anonymity. But even before reaching the threshold of whether an interview is on or off the record, a journalist needs to get that interview. Often personal acquaintance can make a difference.

Are there ways for journalists and government officials to build rapport without getting too cozy or ethically comprised? Would a girls’ night out for reporters and sources be ok if it wasn’t a set up by a paid consultant? Would the White House Correspondents Dinner have been less problematic if it had stayed focused on journalism awards and scholarships and hadn’t become a red carpet gala?

Thanks to the #pandemic, we can ponder these questions from our home offices with no immediate prospects of being invited anywhere to meet a source in person. Back in D.C., there will be no White House Correspondents Dinner or Gridiron dinner or other so-called media proms. Perhaps the coveted ticket these days will be a zoom with a new Cabinet member. It won’t be the same, but maybe that is good for the credibility of both journalists and those they cover.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This brings up so much Linda. So many of the ethics cherished by the profession have to do with access and money, and they rightfully presume an underlying antagonism between subjects and journalists, like between politicians and the powerful versus those who want their secrets. But it’s different for writers–journalists like me–who come in with an agenda or a niche or independently aligned curiosity. That antagonism just doesn’t exist. No money or sex is involved. The subject is just in the same rabbit hole.