Some of us who are obsessing about this election and this President may recall that moment 47 years ago when a different President, Richard M. Nixon, famously – and falsely – told America “I’m not a crook.” Of course, he was. Nixon he resigned before he could be impeached, and Gerald Ford pardoned him for anything he might have done before he could actually be hauled into court. At the time, virtually no one realized that as a candidate, he had likely committed treason.

There have been corrupt administrations, such as those of Warren G. Harding, elected just a exactly century ago, and of Ulysses S. Grant, hero of the Civil War. But few presidents themselves have been considered shady. Lucky us. We have one. Trump has violated not only norms but also laws. Trump has been unusually busy lowering the bar.

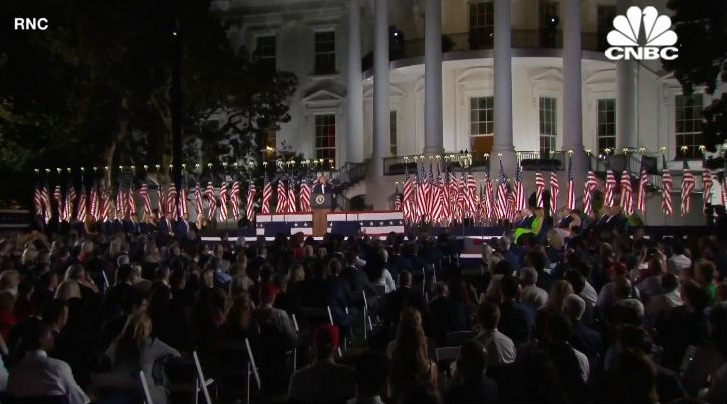

Using the Rose Garden as a stage for partisan political theater is only the latest. How about using the Rose City – and other American cities – as settings for the political theater of federal agents in the street? Or the use of federal park police to clear Lafayette Square so that the president could perform a different bit of political theater, holding up a Bible in front of a church.

So Trump was abusing his office. Was he also violating the law? The Constitution? And is sending federal agents into a state that doesn’t want them a police-state tactic, more appropriate to, say, Belarus than the United States? Now things get more complicated.

Let’s take the issue of sending federal troops. In 1954, the United States Supreme Court ruled that separate education for black and white students was inherently unequal. That meant integrating the public schools. In September of 1957, nine black kids tried to attend Little Rock’s Central High. First the national guard kept them out, then local police didn’t protect them from a white mob. In response, President Eisenhower sent in the 101st Airborne to make sure the Little Rock mobs couldn’t prevent the Supreme Court’s decision (and a subsequent federal court order to hurry it up) from being carried out. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus hadn’t asked for that kind of help.

Five years later, the Kennedy administration sent federal marshals to Mississippi — where they weren’t especially welcome — so that James Meredith could become the first black student at the University of Mississippi. The Marshals Service got extra manpower by deputizing 300 members of the Border Patrol.

I don’t mean to suggest that Trump’s sending federal agents to Portland is equally praiseworthy. It’s not. But sending federal officers into states that don’t want them in order to uphold federal law or the decisions of federal courts is not necessarily bad. Nor is it necessarily illegal. Eisenhower sent the Airborne into Little Rock under the Insurrection Act of 1807, Elizabeth Goitein of the NYU School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice wrote in The Atlantic last year, and “the potential misuses of the act are legion.” For example, “[c]onjuring the specter of ‘liberal mobs,’ [the President] could send troops to suppress alleged rioting at the fringes of anti-Trump protests.”

Cully Stimson, manager of the Heritage Foundation’s national security law program, is a former federal prosecutor and Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, as well as a member of the Stimson family that produced King Broadcasting founder Dorothy Stimson Bullitt. Stimson notes that the federal criminal code lists hundreds of offenses that federal agents can enforce. (Or not. Enforce the Hatch Act anyone?) Arguably, if local police won’t protect federal property, these federal agents don’t have much choice.

Sending federal agents hither and yon has obviously drawn the most attention, but we have been in such a blizzard of questionable– or at least questioned — executive action that it’s hard to keep track. Somewhat lost in the current shuffle has been Trump’s July 21 memo to the Secretary of Commerce — the dynamic and public-spirited Wilbur Ross — announcing as a matter of policy that undocumented immigrants won’t be counted for purposes of Congressional representation.

In addition, Trump has basically said that he wants to cripple the U.S. Postal Service in order to impede mail-in voting. That is arguably an attempt to steal November’s Presidential election. In a similar vein, his moves to alter the census are arguably attempts to steal Congressional elections for the next 10 years. Then there is the administration’s 2018 effort to insert a question about citizenship into the 2020 census. The Supreme Court shot that down last year. Writing for a 5-4 majority, Chief Justice John Roberts said the government could insert such a question, but it had to provide a plausible justification; the justification it had given the court, Roberts wrote, was “contrived.” Cases challenging this year’s run at the census have already been filed.

Don’t bet a lot of money on the feds. “They do not have a legal leg to stand on,” says Tom Wolfe, a senior attorney at NYU law school’s Brennan Center for Justice. “It’s going to be very difficult for any court to rule in favor of the Trump administration.”

Article I, section 2 of the Constitution specified “persons.” It also notoriously let a state count three-fifths of every enslaved person – who, of course, couldn’t vote. The 14th Amendment did away with the three-fifths part. Of course, representation was still based partly on the whole number of women, who couldn’t vote.

What about the – valid but probably irrelevant – argument that the Framers couldn’t possibly have envisioned a world in which millions of people who entered the country illegally may become the basis of Congressional representation and government spending? NYU’s Wolfe chuckles. This isn’t exactly a new argument. He points to Klutznick, a 1980 case decided during the Carter administration, which was brought into the D.C District Court by the Federation for American Immigration Reform. In the court’s words, the plaintiffs argued that “the phrase, ‘the whole number of persons’ does not, in historical context, include illegal aliens, though they agree that the concept includes all lawful residents, citizen and alien alike. Their argument proceeds along the following lines. The concept of illegal aliens was unknown to the Framers; there were no illegal aliens for nearly a century thereafter [until 1875] when the first act excluding certain aliens (prostitutes and convicts) was passed. Arguing that an intent to grant representation to persons unlawfully within the country therefore cannot logically be attributed to the Framers…”

The court also noted that the Census Bureau “responds that it is constitutionally required to include all persons, including illegal aliens, in the apportionment base, insofar as an accurate count is reasonably possible. Furthermore, as a practical matter, it contends accurate methods to count illegal aliens do not presently exist.”

The court never decided that case on its merits. Rather, the judges ruled that the plaintiffs lacked standing. But they observed that “[t]he population base used for apportionment purposes consists of a straightforward head count. . . . This has been the practice since the first census in 1790.”

The Constitution is absolutely clear, Wolfe says; the people who wrote it certainly knew enough about the English language to have specified “citizen” if they had meant it.

“This is just regular interpretation of the law,” he explains. Beyond the written language, he says, “we also look to practice to see what’s legal and what’s not.” Historically, “this has not been a partisan issue.” He refers to memos from the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush saying that the Constitution requires counting everyone. This isn’t a new idea. ” In 203 years of censusing,” Wolfe says, “they’ve always counted everyone.”

But, as they say, past performance is no indicator of future results. Trump and his supporters obviously hope that if you pack the courts with enough conservative judges, they’ll start ignoring precedent. Some have indeed started doing that. But there are some bedrock Constitutional principles that even most Trump judges would presumably find it hard to jettison.

One of those is the requirement that a police officer who takes a citizen into custody must have “probable cause” to suspect he or she has committed a crime. This is less than the standard used to determine guilt. But it’s more than zero. “Probable cause exists,” the Supreme Court observed in its 1949 Brinegar decision, “where ‘the facts and circumstances within their (the officers’) knowledge and of which they had reasonably trustworthy information (are) sufficient in themselves to warrant a man of reasonable caution in the belief that’ an offense has been or is being committed.“

Virtually no one argues that it’s OK for federal agents to pull people off sidewalks and throw them into unmarked vans without such “facts and circumstances.” And yet that’s allegedly just what has happened in Portland. “I would be very disturbed if that’s true,” Stimson says. “If officers are arresting people at any time without probable cause, that’s a big issue.”

One of many.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.