In 1997 Jimcy McGirt, a member of the Seminole Nation in Oklahoma, was convicted in state court of sexually molesting a four-year-old girl on the nearby Creek Reservation. On July 9 of this year, the U.S. Supreme Court in a 5-4 ruling set his conviction aside. Arguing for the majority, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that promises made in the 1857 treaty between the United States and the Creek Nation establishing the Muscogee Reservation still obtain today.

“We hold the government to its word.” Gorsuch wrote. “If Congress wishes to withdraw its promises it must say so.” Because the reservation is recognized as a sovereign nation by the United States and subject to federal law, one of the promises is that McGirt can only be tried in a federal court.

Presumably thousands of such verdicts in Oklahoma must now be voided and retried. This vision of legal mayhem prompted Chief Justice Roberts to argue in his dissent that the decision “…creates significant uncertainty for the State’s continuing authority over any area that touches Indian affairs ranging from zoning to taxes to family and environmental law.” To which Gorsuch replied: “Dire warnings are just that and not a license for us to disregard the law.”

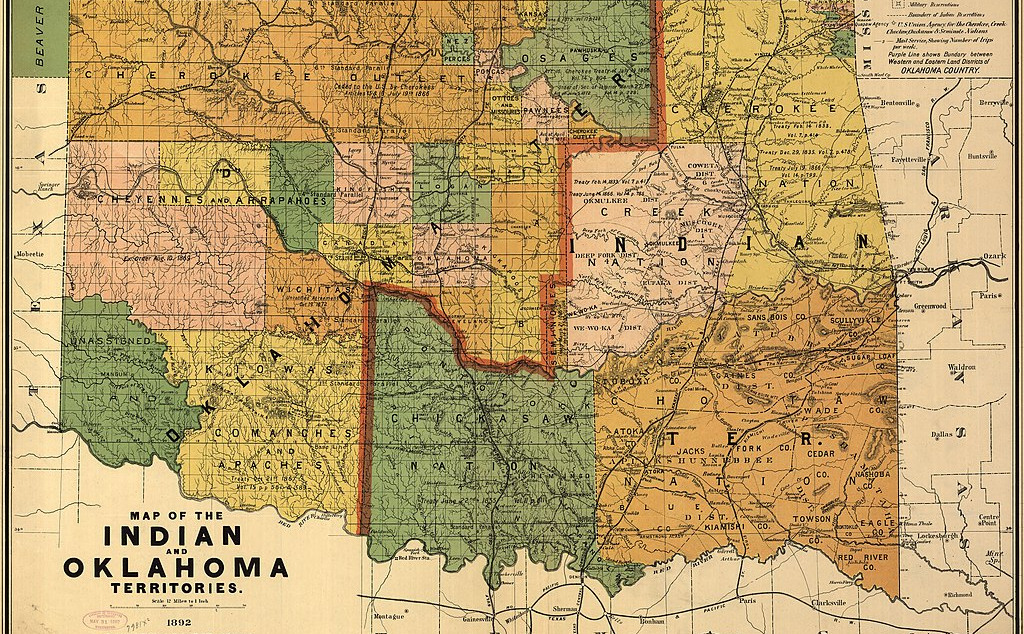

A little history underscores the complexities of the case. The Muscogee Reservation is one of five in eastern Oklahoma created by the federal government in the 1830s to house the Five Civilized Tribes: the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole. All had been driven by armed force from their homes in the American Southeast.

The Cherokee “Trail of Tears” was just one horrific episode of an immense program of ethnic cleansing carried out by land-hungry citizens, greedy speculators and those they voted into Congress and the Presidency that drove hundreds of thousands of native people west across the Mississippi River to an area loosely defined as “Indian Country.”

People of a certain age will remember Walt Disney’s TV epic about Davy Crockett, and the songs that accompanied it when, in his early years, Davy participates in a bloody episode of dispossession during the Creek War of 1832, “when the Creeks was whipped, and peace was restored.” Another young westerner, Abraham Lincoln, served as a Captain of the Illinois Militia during the 1836 Blackhawk War.

In Knox County, Illinois, the Denny, Boren and Bell families, founders of Seattle, heard as children stories recalling the doleful lament raised by exiled Miami Indians driven across the country toward the setting sun. To mitigate the trauma, Louis Cass, then Secretary of War, as part of “An Act to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indian tribes and preserve peace on the frontier,” passed in 1832, had Congress make a solemn pledge to the dispossessed that the western lands would be theirs forever. “Forever,” in this case, was a little over 20 years until Congress punished Indian Country tribes for their support of the Confederacy by eviscerating the promised lands.

These lands were further diminished by the Homestead Act of 1862 and the Dawes Severalty Act, passed in 1887, that sought to speed the process of assimilation and encourage individual Indians “to assume a Capitalist and proprietary relationship with property.” To satisfy a clamoring electorate, tribal lands were broken into individual private plots and the “surplus” sold to non-Indians.

Proposals to organize Indian Territory into a state, a century in the making, resulted in efforts to combine remaining Indian reservations into the native state of Sequoyah, but Congress passed the 1890 Oklahoma Organic Act creating a single Oklahoma Territory from native and non-native land. It also required of the future state constitution that, “Nothing entertained in the said [state] constitution shall be construed to limit or impair the rights of persons or property pertaining to the Indians of said Territory.”

The passage of the Oklahoma Enabling Act of 1906 that extinguished Indian Territory created the new state of Oklahoma, which was about to enter an oil boom. As the chorus in the musical “Oklahoma” sings, “We know we belong to the land (YO HO) and the land we belong to is grand!” But did the disappearance of Indian Territory mean the disappearance of reservations?

That was one of the issues before the Supreme Court. The Indian Appropriations Act of 1885 satisfied rapacious Oklahoma land speculators by “allowing” tribes and individuals to sell land they claimed was theirs, apparently gutting the reservations. A section of this act also held that certain crimes committed by Native Americans on native lands came under federal jurisdiction. One of these crimes was rape. The law was updated in 2013 to include assault against an individual less than 16 years old and felony child abuse or neglect, charges brought against McGint.

Along with Justices Ruth Bader-Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, Gorsuch argued that the reservations still existed as legal entities as did federal jurisdiction for crimes listed in the updated Major Crimes Act. Carried away by the euphoria of statehood, Oklahomans apparently assumed the reservations were relics of the past. The Supreme Court has just differed, maintaining that the reservations are as real today as when they were organized in the 1830s. Today, Oklahoma faces the fact that most of the eastern half of their state remains native land where native rights must be respected. The birds circle.

Something similar happened in Washington State in 1989 when the Puyallup Tribe of Indians sued in federal court claiming they still owned 12 of the 18,240 acres of their original reservation that the Port of Tacoma dearly wanted to develop. Since the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek and the Fox Island Council negotiations of 1856-7, white settlers and officials had employed every piquant means of inducement — bribery, chicanery, thievery and outright fraud — to fleece the Puyallups of their land.

But the court determined that even if most of the land had been sold, the reservation still existed, and members of the Puyallup Tribe still had rights that must be respected. In the Puyallup Tribe of Indians Settlement Act of 1989, the tribe ceded its rights to property in exchange for $162 million and other benefits. Justice did not come cheaply.

Seattle puts itself in this story as it continues to stymie efforts of the Duwamish Tribe to gain federal recognition. Their Chief, Seattle, led the native delegation at the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, and the Duwamish were its first signatories. In exchange for thousands of square miles of their land, the Duwamish were given promises they have labored 160 years to have redeemed. They were promised a reservation they never received and promised rights they cannot access.

Their arch-enemy in this grotesque fraud was the city of Seattle, which did everything it could to ensure that not a single square inch of Duwamish homeland would be reserved to them. To seize the land, settler greed was marshaled against them. Thus, the federal government judges the tribe landless, and without land undeserving of recognition as a tribe.

Cruel fraud, theft, and monstrous indifference have made this injustice persist. Today, Mayor Jenny Durkan allows that yes of course, her city inhabits Duwamish land, but she and her officials lift not a finger to right the screaming wrong. Sooner or later, justice will be done. The birds are coming home to roost.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You’re right. Those acknowledgments that we occupy Duwamish land are being made at arts and cultural events all over the city these days. And that’s fine. But it’s not enough.