I regard myself as an antiquarian rather than an historian. I came to this juncture in my early 20s after attending a soiree for graduate candidates in the History Department at the University of Washington. This was in the mid-1960s, and there were people of my age wearing rumpled khakis, tweed jackets with suede elbows patches, gnarly black frame glasses.

Some were smoking pipes. Not handsome meerschaums with the elegantly carved face of a bearded, one-eyed pirate on the bowl mind you, but those stupid straight ones, a la Hugh Heffner, that stuck out of their faces like plumbing fixtures.

Then and there I decided becoming a historian was not for me.

I have been happy in my choice. There are many fewer antiquarians afloat these days than historians, so the need for protective elbow patches is minimal. Which brings me to the Port of Seattle.

In its efforts to be more approachable, the Port has invited the public to help name the parks it is developing at the old terminal sites 103 to 117 on the Duwamish Waterway. Now, there is a red flag! Remember the bathetic effort of Great Britain’s Natural Environment Research Council to open the naming of a new polar research vessel to the public via the internet? The winning result was “Boaty McBoatface.”

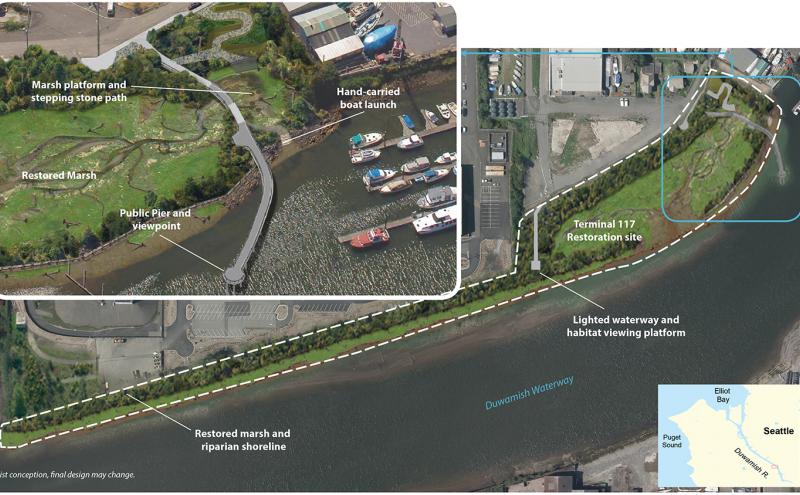

I was asked to submit ethnographic material regarding the native names of the terminal sites particularly Terminal 117. Located on the west bank of the waterway across from Boeing Field, the site is where the old Duwamish river channel curved before the engineers straightened it in the early 20th century.

West of this riverbank, three low, rocky hills march across the valley bottom from its west wall. One of these was crowned by the notorious Briscoe Memorial Boys School, but the Duwamish people knew it in their native language, Whuljootseed, as Qiyawa’lapsƏb (qee-yah-WAH-lahp-sub). The early 20th century anthropologist and linguist Thomas Talbott Waterman, who collected the place name in the 1920s, said his informants thought it sounded something like eel’s throat.

Readers will recall this as one of the great mysteries of early Seattle history: what did eel’s throat refer to? This section of the river is bracketed with myth sites and the mythic heart of Duwamish country lies little more than a mile upstream. In Coll Thrush’s 2007 history: Native Seattle: Histories From The Crossing-Over Place (University of Washington Press), anthropologist and linguist Dr. Nile Thompson translates the name as “Beach Worm’s Throat.” The beach worm, probably a great big ugly polychaete, could be found in driftwood and used for bait. Thompson opines that Waterman’s informant did not know the precise English name for the animal described, so chose one that looked something like it. In support of his re-translation, he offers the Suquamish place name, sQuya’wub (sqoo-YAH-wub), from the Whuljootseed Quya’w (qoo-YAHW), “long green grubs.”

With this in the back of my head as I poked through data for the terminal sites, it suddenly hit me: CI’CKADIB!!! The whuljootseed word, TSEETS-kah-deeb, “clitoris,” names a little promontory just across on the river’s east bank that refers to a myth in which Mink, a frantically lascivious bumbler, asks his grandmother if he can use her clitoris for bait. There it is! We have the green beach grub on one side of the river and grandmother’s tumescent clitoris on the other. And what do you suppose Mink choose? No better way to hurry on parturient spring, which reciting the myth was expected to do.

One of the parameters the Port asked me to follow in my research is to make sure the outcome has “enticing facts” directed to a “middle school reading level.” I taught middle school, high school, college for 30-plus years. Middle schoolers are the best of the lot but require care. I typically began 7th grade year by asking how many students were or were approaching age 12? Most raised their hands. I write MORON in large letters on the white board, a comparative term they are likely to hear describe them and not to their advantage. Silence. I invite a student to come up and read the definition from the immense dictionary on my desk: “An individual with the mental capacity of a 12-year old.” It is only a clinical term.

Middle schoolers have no hidden agendas and rabid, carnivorous brains. They soak up everything, are fiendishly clever, first-rate learners and wildly fun. For them, the word clitoris alone would represent enticement on a thermonuclear scale. It requires subtle intelligence to present knowledge to a middle-schooler in any effective way, but with grandmother’s clitoris at hand, once the screams and gagging, the fingers down the throat and falling on the floor subside, it’s a done deal.

The park in question is located smack-dab in the middle of a significant mythical area. It cannot be ignored, and any effort to bury this ”Boaty McBoatface” with a euphemism or a diverting expression of namby-pamby propriety would be laughed to scorn. I delight to think what the Port will name this family friendly, middle-school-literacy-level park? Granny’s Clit? Grandmother and Mink get it on?

To save it grief I’ll recommend the use of waqˀwaqˀu’s (wahq-whaq-OOS), “frog’s face,” the native name for the February lunation, or the traditional response when people greeted the frogs’ bumptious chorus by announcing “Mink is coming ashore!” Fleeing retribution for killing his nephew, Mink hides in a swamp with his frog-sisters who keen loudly over his idiot misfortune: “Wahk-HE-eh, Wakh-HE-eh.”

Mink the bumbler finds his mythic parallel in Aristophanes’ slapstick comedy Frogs, where Dionysus’s ludicrous effort to improve the state of drama in Athens leads to his humiliation and abuse. The frogs steal the show with their equally mindless ear worm: Brekekekex koax koax.

Antiquarians pick up on these things.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Did anyone think to consult with the Duwamish People?

I grew up in the duwamish river in Seattle I was that’s a little child with my grandparents my grandfather was Indian and my grandma I lived and went to school there we would play in the river and the creeks that would run into the river as a child we would watch the drive in movies play along the river banks and walk to south park to go shopping and back home along Marginal way back then as Boeing moved in the river started to turn bad, back then as a child growing up along river was fun for a children we didn’t fear pollution back then I thought the river would all ways be there with the wild and the woods that all of played in back then So sorry that the country has let this beautiful part of my life get destroyed as now I have great grandchildren they never get to feel what I felt as a child as now I am 76 years young we used to have all my family get together there my grandparents were the local gardeners they would pass the food out to all our local neighbors and whatever was left after she got done canning they take to the public market in downtown Seattle times were different then I’m sorry to see that the river is being destroyed and the county is not doing anything about it I wish I could help it would mean everything to me to be able to tell people what it was like by then back then it used to be a beautiful place