History was rhyming all over the place Monday night as riot-geared police and mostly riot-wary protesters faced off at 11th and Pine and the taunts, tear gas, rubber bullets, water bottles and bottle rockets flew. This intersection is Seattle’s OK Corral, the place where stormin’ crowds and cops go to stage their showdowns.

I only watched this showdown through the small screen I’m now typing these words on; I thought I was done with this sort of thing after a decade as the Seattle Weekly’s riot guy, spending day and night chasing the upheavals provoked by the first Bush vs. Iraq war, in 1991, the acquittal of the Los Angeles cops who beat Rodney King in 1992, and the disastrous World Trade Organization meeting here in 1999. But the feeling of déjà vu all over again is too strong to turn away.

Rodney King’s name doesn’t come up often these days; since then, too many black men have died at the hands of police in full view of the world, and never gotten a chance to plead for everyone to get along. But you can draw a line from the LA cops’ weirdly deliberate, almost ritualistic beating of King to the weirdly deliberate slow-motion suffocation of George Floyd. King’s ordeal took place when cellphones and the World Wide Web were still novel technologies and only came to attention because a bystander caught it on videotape. Broadcast and re-broadcast unendingly, it drilled as deeply into popular consciousness as the killing of George Lloyd, launching a new era of public oversight, if not reform, of police violence.

There was one difference: In 1992 public outrage waited until the officers involved were acquitted of assault charges to erupt, even though hopes for conviction were dampened when their trial was moved to a conservative suburb called Simi Valley, home to many LA police officers. Such patience has since frayed.

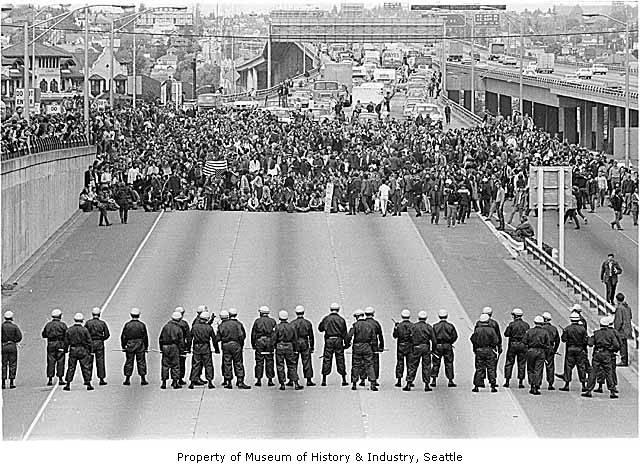

When the rage erupted, it charted a new riot geography for Seattle—drawing a map that seems to have informed the Seattle Police Department’s riot strategy, and its readiness to use overwhelming, preemptive force, today. Two decades earlier, anti-Vietnam War protests had centered around the UW campus, famously spilling over to block I-5 on May 5, 1970. (It’s remarkable how thin and lightly armed the blue line facing off against them in this Seattle P-I photo looks in our age of armored, militarized policing.) In March 1991, the legions protesting the looming Gulf War proceeded downtown, massed around the federal building, and then gathered for a candlelit vigil at Seattle Center that seems quaint in retrospect.

On April 29, 1982, when the Simi Valley verdict was announced and Los Angeles’s and Miami’s streets erupted, Seattle stayed quiet until late in the evening, when a small, unannounced protest mustered at Third and Pine. It scattered after police arrived, and small bands then rampaged around downtown, lighting dumpster fires, overturning cars, and smashing and grabbing from store windows. The next day Mayor Norm Rice, Reverend Sam McKinney, the dean of local black pastors, and Jesse Wineberry, then the state’s only black legislator led an awkward peace at Martin Luther King, Jr. Park. “I’m sick and tired of all the talk,” one attendee roared from the back. “Like Jesse said, it’s been 20 years. All that diplomatic stuff is dead. It’s time to take to the street! If it takes bloodshed, fine!”

Bloodshed was blessedly absent, even from the melée that came later that night. Demonstrators first thronged around the Federal Building (since superseded by Westlake Park as downtown’s protest plaza) for speeches and chants. I overheard one seasoned white rabblerouser murmur to his companions, “When the sun goes down, we’ll take this town.” As the protestors dispersed, he rushed out into Second Avenue and called on them to regroup: “You’ve got to stay in the street!”

Downtown, more vandalism ensued, but the ethos was more about partying hard and breaking shit than smashing the state. Suburban white kids arrived to take pre-selfie pictures of each other on the front lines of social justice. One to two hundred more focused demonstrators massed and marched up Madison to Capitol Hill. They reached the new East Precinct HQ at 12th and Pine and smashed a few windows there and at the state liquor store across the street. The East Precinct forces gathered and, led by the mounted cavalry, pushed them back downtown. There, the downtown battalion was waiting. It pushed them back up Pike Street, then stopped above I-5, at the precinct border, and fell back.

This time the East Precinct forces were unable to contain them. The demonstrators-turned-rioters, aggravated and agitated by all this pushing and prodding, dispersed across Capitol Hill and did the week’s worst damage. The hill’s smaller, tight-packed wood and wood-framed buildings were more vulnerable to arson than downtown’s tower blocks. Roving vandals lit about 30 fires. They torched one apartment building at Summit and John, seriously damaged an adjacent one, and turned a rocket-shaped fuel tank in a vacant lot near 14th and Pike into a giant Roman candle. Suburban fire companies arrived to help put out the blazes. But though 63 people were killed in LA’s riots, no one died in Seattle’s.

In 1999, much larger, more broadly based, and meticulously planned anti-globalization demonstrations occupied the downtown retail and hotel district, blockaded the Washington State Convention Center and Sheraton Hotel, and shut down the World Trade Organization meeting, the biggest event ever hosted by this aspiring world city. Police, who’d badly underestimated the scale of the protests, held the perimeter around the hotel and convention center and largely consigned the rest of downtown to a free-rampage zone.

Once again, when night fell, police pushed the protesters up to Capitol Hill. This time, however, the crowd did not disperse to wreak random mayhem. It kept marching, up Pine Street, toward the week’s climactic confrontation.

I spent all the night watching what ensued and posting a report on the Seattle Weekly website. (Though the Weekly’s now gone, its digital content endures, at least for now.) The crowd from downtown merged with another that had marched down Broadway in a scheduled protest against the planned execution (since overturned), of the activist/writer Mumia Abu-Jamal for the murder of a cop. Police broke them up with the usual nonlethal weapons. Then, according to eyewitnesses whom I talked to and who called in to KUOW the next day, they pursued straggling protesters and random passersby with a fury not seen downtown—attacking customers emerging from restaurants, grabbing one man who was talking on a pay phone, knocking down and pepper-spraying one woman walking to her car and spraying another who was sitting in hers. Incensed, the protesters rallied east of Broadway on Pine, facing off against the police two blocks to the east.

Global trade issues, even Free Mumia, seemed forgotten; at a certain point resistance takes on a logic and a will of its own. The people milling on Pine Street, largely white, talk of defending their neighborhood, their right to exist, against an occupying force; neighbors trickle in to join them. “Go home! Go home!” becomes the chant of the hour. “Get off our hill! Get off our hill!”

Still, the crowd exerts collective self-control. One young man gathers up loose bricks along the curb and drops them into a mailbox, to make sure they don’t get thrown. Two black-garbed, black-masked figures (back when masks meant something) begin pushing a dumpster into position to roll at the cops. Others block them and push it back.

This time the police are better prepared to defend what they, like their challengers, see as their turf. They gather at 11th and Pine in a riot-geared phalanx, backed by State Patrol officers. Stave-wielding National Guard troops guarded the side streets. Behind them loomed “the Peacemaker,” a tank-sized armored vehicle equipped with a water cannon.

The crowd edges forward, closing the gap. I hear some members murmur about “getting the police” and others urge them to hush up and stay peaceful. A loudspeaker atop the Peacemaker booms, “It is illegal to block the street. If you do not leave, chemical irritants and other weapons may be used against you.” Suddenly, a balding, goofy-looking guy in suit and tie, who looks like a taller version of the then-young Jeff Bezos, intersperses himself between the two sides: Brian Derdowski, a maverick Republican King County Council member and ardent critic of unbridled local development and global trade. He exhorts the demonstrators to back off, assuring them if they do he’ll get the police to do the same. Many do, and the Derd turns to the thick blue line and pleads with them to do the same, to deescalate the confrontation. The officers stare impassively at him.

Without further warning, the flash grenades fly, then the gas canisters, first into the crowd, then in front of it, so the protesters are forced to draw back. For the next three hours the confrontation seesaws back and forth, as clouds turn to drizzle and then rain. The crowd edges back. Derdowski, now jacketless, sweating, and flush with tear gas, shouts himself hoarse, again persuading the crowd to step back. He begs the police for a reciprocating gesture. No response. He asks them for a megaphone so he can address the crowd. Nope.

Others try to propitiate or exorcise the police with street-performance offerings (this is Capitol Hill, after all). One gathers soggy leaves from the gutter and spreads them in an intricate pattern. Another ceremoniously lays oversized “Clintonbucks” before the cops. Another stands with his back to the phalanx and his arms spread, an American flag hanging like wings. The police decide he’s too close and drag him and his flag away. The guy who dropped the Clintonbucks comes back and burns them. Two couples waltz through the DMZ. A skateboarder weaves across it.

The crowd begins singing, earnestly: the theme from the Brady Bunch, “Kumbaya,” “America,” and finally “Silent Night.” The confrontation seems to be easing off to a peaceful good night.

With no audible warning, the loudest blast I’ve heard all week sounds, and a heavy volley of plastic bullets, flash grenades, and gas shells clears Pine Street again. The police squad leader lifts his baton and the Peacemaker backs up. Most of the crowd drifts away; what can you say after singing “Silent Night”?

A year or so later I got a call from a documentary producer. He and his colleagues were making a film—for Frontline, perhaps, I don’t know if it ever aired—on the militarization of policing. They’d seen that post. They were coming out to Seattle and they’d like to interview me. Sure, I said.

As it happens, they were from Minneapolis.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.