Last week the Third Door Coalition, a self-described “unlikely alliance” of representatives from the business, human services, government and advocacy worlds, unveiled a proposal to bring an end to chronic homelessness in King County. Their pitch, which they call “an invitation to the entire community,” is the result of two years of effort to put their differences aside and focus on a solution.

Their proposal is not an attempt to boil the ocean: they are not proposing to end all homelessness, or solve the larger affordable housing issues in the region, or eliminate all the downstream effects of the homelessness crisis. Their focus is on one particular slice, chronic homelessness: those who have been homeless for one year or longer or for a total of 12 months over the past three years, and who have a disability that prevents them from maintaining work and makes it difficult for them to maintain stable housing. Estimates are that there are about 6,500 chronically homeless in King County; about 30% of the homeless population, but the most visible, the most vulnerable, and the most costly to the community when they are homeless.

As I have written before, over the last few years there has been a move to stop treating the entire homeless population as an undifferentiated group and instead focus in on solutions that are tailored for specific sub-groups with distinct needs. For the chronically homeless, the best practice is clear and well-established: permanent supportive housing (PSH). It combines affordable housing in units that accommodate their disabilities with a set of “wrap around” services that support them in place to get stabilized, treat their individual conditions, find and keep steady employment, and manage day to day life.

Last October the City of Seattle reported that over 2,100 households were stably housed in PSH. The chronically homeless are not the only clients of PSH programs, as there are other elderly and disabled individuals in our communities who also benefit from PSH programs as well and are not able to live independently. Permanent supportive housing is not intended to be a time-limited intervention; there is a recognition that many PSH residents will never be able to live independently again and will likely remain in a PSH facility for the rest of their lives. But PSH is also not “free rent” — residents are expected to pay 30% of their income, the standard beyond which someone is considered “rent burdened.”

Currently there is a gap of about 6,500 units of PSH between the established need and the number of units available. While an additional 950 units are currently expected to be built over the next six years, the demand is expected to grow at essentially the same rate, so by 2026 if nothing changes, the situation will be exactly the same as today.

The heart of the Third Door Coalition’s proposal is to close that gap, by funding the construction of an additional 6,500 units of permanent supportive housing in King County. That would be sufficient for the city to move the entire chronically homeless population off the streets and keep them stably housed over the long term so they don’t return to homelessness.

The diverse interests in the coalition have banded together to do a deep analysis of the costs of affordable housing, which has a reputation for being expensive — far more expensive than commercial housing developments. In a report generated by the coalition, however, they reject that as a myth, attributing much of it to differences in accounting methods between the two (such as how financing costs are accounted for). They also have made a list of ways to bring the average cost-per-unit of housing (about $332,000) down substantially. By employing a number of methods on a portfolio of different projects (not all the methods apply to every project), they believe they can achieve a 14% savings, getting the cost down to about $284,000 per unit.

They identify five ways to lower the construction costs:

- Changes to land use codes. They argue that permanent supportive housing should have its own unique building code that is not optimized for market construction and enables more flexibility in construction, permitting and development. It might also remove requirements for things such as street-level commercial space and bike parking.

- Regulatory exemptions. They believe that exempting PSH projects from certain fees, taxes, and permitting requirements could save up to $35,000 per unit.

- Reducing land costs. Last year the state legislature made it easier for cities and counties to repurpose surplus land for affordable housing projects, and the City of Seattle has already begun to take advantage of that opportunity to bid out projects for specific city-owned sites. To the extent that public land is available, that could be additional savings. However, public land tends to be less available in larger cities, but the farther out one goes, the harder it is to keep PSH projects physically close to important services (such as healthcare) that residents depend upon.

- Consolidating funding and financing. The coalition refers to this as the “capital stack,” a fancy name for “all the places the money comes from.” The important insight is that most PSH projects cobble together funding from a number of public and private sources. The Seattle Office of Housing has become expert on this, and can leverage outside funding to get a unit of affordable housing built for as little as $50,000 of city funds in some circumstances. But the downside of that is that it takes time, effort and expertise, and introduces a significant amount of risk and delay into the development process. By consolidating funding contributions from multiple sources into a single fund, they believe they can simplify and expedite the process.

- Alternative construction techniques. By looking at newer construction materials and techniques, the coalition believes it can save as much as $87,000 per unit. There are trade-offs however: materials such as cross-laminated timber introduce height limits into buildings, and modular or pre-fabricated construction techniques limit the ability to have a variety of layouts for units.

By leveraging these five methods across a portfolio of development projects, the coalition believes it can significantly lower the average per-unit cost and stretch dollars further. It will require enabling legislation at the state and local level, and finding development partners who have the requisite expertise to leverage these approaches.

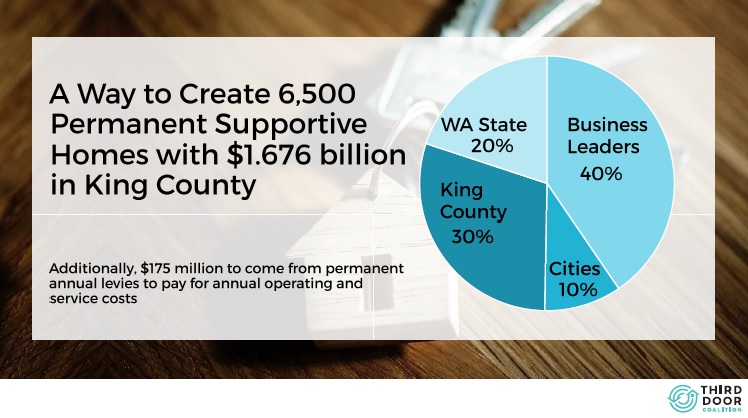

By their calculations, building the needed 6,500 units of permanent supportive housing will cost $1.676 billion dollars over five years, plus an additional $175 million per year in perpetuity for operating and service costs (part of which is covered by residents’ rent payments). They propose a public-private partnership to raise that amount in a single fund, authorized and created under state law. In their initial proposal, 40% ($670 million) would come from businesses, 10% ($167 million) from cities, 30% ($502 million) from the county, and 20% ($334 million) from the state.

At yesterday’s press conference announcing the proposal, the coalition leaders were joined by several public officials from the City of Seattle, King County, and the state legislature. That included City Council members Herbold, Lewis and Mosqueda, and State Representatives Nicole Macri and Frank Chopp. The coalition also released a letter with a longer list of business leaders, public officials, and other community stakeholders who supported the proposal.

It’s an intriguing proposal. The timing is interesting: it’s obviously not a good time to be fundraising (and $1.676 billion is a lot of money to raise), but a recession is a great time for a jobs program — and housing construction creates a lot of jobs. Also, Seattle’s sky-high construction costs might actually decrease a bit in the next few years, depending on how deep the recession takes us.

The other interesting part of the proposal is that it’s the first one to propose actually solving a part of the homelessness crisis — and one of the most challenging parts — rather than trying to just incrementally increase the investment. Council member Herbold commented on that, saying that she had been advocating for doubling the city’s investment in PSH because she knew how to do that; but now with the data, analysis and framework provided by the Third Door Coalition, there is a hard target. Again, this won’t solve the entire homelessness crisis: it won’t stop people from entering the homeless system, as other investments in prevention, diversion and affordable housing are needed to accomplish that.

The coalition members have also provided context for the fundraising goal, pointing out that the operational costs to support one chronically homeless person in permanent supportive housing — about $18,000 per year — is the same as the cost of incarcerating someone in King County Jail for three months, or for three days of inpatient care for an individual at Harborview Medical Center. A 2013 research study found that when homeless individuals are placed in PSH, the overall cost savings because of reductions in hospital services and jail bookings averaged about $62,000 per person.

In the press conference Council member Lewis emphasized this point, saying that many people think of jailing the chronically homeless as “a free option for dealing with chronic homelessness” when in fact it’s very expensive.

When Rep. Macri was asked if she was committed to proposing the necessary state legislation at the next session (which might be as soon as next month), she was a bit vague in her response, though she pointed to her track record over the past two sessions in creating new revenue streams for local governments to put toward homelessness response and affordable housing. She did call out the data and analysis framework supplied by the coalition, however, as “incredibly helpful to us” in making the case for the legislation.

Herbold, Lewis and Mosqueda were all enthusiastic about their prospects to move the proposal forward, with both Herbold and Lewis saying that the city’s share of the fundraising should be achievable (about $32 million per year for five years).

The other interesting aspect of the proposal is, of course, the contrast between it and the Sawant/Morales “Amazon Tax,” There are similarities as well: Sawant’s plan would pay for affordable housing — of which it is assumed that PSH would be a portion — and for “Green New Deal” programs, both of which she has recently been pushing as jobs programs as well to make them more attractive in a recession. But the “Tax Amazon” campaign paints the business community as the enemy, to be demonized, castigated, and of course taxed. Whereas the Third Door Coalition brings the business community to the table, and in particular the local hospitality industry. Chad Mackay, of Fire and Vine Hospitality and a leader of the coalition emphasized that point, noting that the hospitality industry has been devastated by the COVID-19 shutdown “and yet here we are showing up.” Though notably absent are the big players in the Seattle region business community: Amazon, Microsoft, other tech companies, and of course the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce — at least so far. The coalition’s web site says that it has intentionally kept membership small to streamline decision-making, but that will need to change as they try to build broader support for their proposal. In the meantime, the “Tax Amazon” campaign has attacked the Third Door Coalition, saying, “While certainly we support any additional funding for affordable housing, we have to read past the heartwarming rhetoric and see the formation of this group for what it likely is – another attempt to confuse, divide, and derail our Tax Amazon movement.”

Seattle was also the only city in King County represented at the press conference, and as we learned last year with the formation of the regional homeless authority, getting Bellevue and the smaller cities on the same page as Seattle is not a simple task when it comes to homelessness strategy. But Leo Flor, Director of the King County Department of Community and Human Services, sounded optimistic that the coalition’s proposal would play well outside Seattle. “I have yet to encounter any community in the county that disagrees that housing is better than shelter,” he said.

Sara Rankin, a law professor at Seattle University, director of the Human Rights Advocacy Project and also a leader of the coalition, noted that the framework they unveiled does not yet have all the answers, and that they will be holding a series of sessions to drill down on aspects that need further work.

Lewis also touted the first meeting of the new regional homeless authority scheduled for Thursday morning, which he hopes will take interest in the proposal. “I think we can make a compelling case to this group.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

There are several groups of homeless people. This is a good solution for 30%. Now for the 70%?

Ah, but this is the 30% that is the most difficult to solve for. For youth and young adults, the best practice is transitional housing. For families, Mary’s Place is making huge strides. For the native Americans there are a couple of local organizations doing great, customized work for them, most notably Chief Seattle Club. There is more work to do for specific demographics, but there are also some really good diversion and rapid rehousing programs that are scaling up, catching people at the point they first enter the system and getting them back out of it quickly.

There’s a good argument to be made that solving the chronic homelessness program will have a huge, positive effect on the community since they are the most visible and the ones most likely to have drug and mental health issues that cause issues for the people and places surrounding them.

Thanks for this story. We have to find something that works but it doesn’t have to be one single thing. There is a story in the New Yorker now about how people in San Francisco are discovering that one solution does not fit every category of homelessness: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/06/01/a-window-onto-an-american-nightmare