Seattle has long been ambivalent about tourism. Now, with the state Convention Center’s $1.8 billion expansion in financial trouble, we are learning how very dependent on tourism we have become, almost inadvertently. “The visitor industry is the core of our regional economy, with the Convention Center at its heart,” King County Executive Dow Constantine declared at a press conference last week.

How did that happen? Is this wise? Can the pandemic produce a glide path to a kinder, gentler tourism? And has anybody got a better idea for how to use the Convention Center expansion, now one-third constructed?

As you may have noticed, tourism has become a powerful lobby in Seattle: hotels, restaurants, event planners, visitor attractions, downtown retail, airlines, orcas, sports. It’s not likely, with this much clout, that the convention center expansion will be left as a bombed-out Coventry Cathedral. We just discovered that the expansion needs to sell another $300 million in bonds to finish the job (planned to open mid-2022), at a time when buying such bonds is not ideal. So there will be a raid on federal troughs and, more likely, a hit on local taxpayers and lodging taxes. Former Mayor Mike McGinn, a convention center skeptic, called for “a hard look” at these “too-big-to-fail” megaprojects. Likely there will be a squishy-hard look at tourism’s capture of the regional economy. But this big horse is out of the barn.

Partly because of all the doubts about convention centers and tourism, the visitor industry has had to sneak into town and seize odd opportunities. The state still is reluctant to fund tourism promotion. But Topsy is what we suddenly have grown.

The local case against tourism is long-standing and cogent. The weather provides a short season each summer. Hotel rooms languish in the winter and are hard to find in the summer. Other cities have way bigger convention centers and a big head start. With the new $1.8 billion expansion, Seattle’s will have about 1.5 million square feet, spread over three buildings; giants like Chicago, Orlando, and Atlanta have 9, 7, and 4 million square feet respectively.)

The employment in tourism is low-pay and seasonal (meaning lots of unemployment insurance). Tourism can bring too much of a good thing, such as the throngs at the Pike Place Market when a cruise ship is in town. Tourist ghettos drive up prices and drive out local places. Turning to tourism is normally a last-gasp cure for cities with economic woes, not humming economies like Seattle’s.

So how, aside from various Boeing Busts, did tourism take such root in this city? First was the suburbanization of downtown retail. Upscale shoppers fled downtown and developers filled up the anchor stores with tourist shoppers. Second was the change in federal laws that enabled cruise ships serving Alaska to use Seattle as a port of embarkation.

Third was the growing clout of hotels. It used to be that Seattle couldn’t attract the convention business because it had too few hotel rooms. Hotels were reluctant to expand because of those long rainy winters. And so, about 40 years ago, hotels and retailers pushed for a convention center, funded by lodging taxes (currently 9% in Seattle, 2.8% in the rest of the county). It was all part of Seattle’s quest to be Major League. The late start also meant we were entering a national market where there are too many other convention centers carving up the business. (And now, thanks to the coronavirus, WAY too many for the market.)

But where to build the convention center? Typically, these are built on cheap land, such as over railyards. It came down to — a tough call largely made by civic icon Jim Ellis — the Seattle Center (east of the fountain) or snug up against the downtown Sheraton Hotel. (Guess who won?) However, the dubious Sheraton-adjacent winner alongside I-5, is on a small site, incorporating the landmarked old Eagles Auditorium (now ACT Theatre) and an expensive lid over I-5. The site was expanded across the block to the north in 2001.

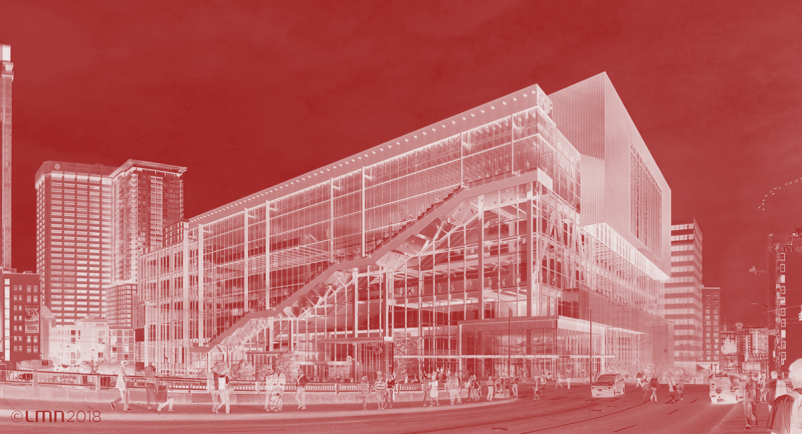

We are now building the third expansion, a full block to the northeast and over the old Metro bus lot. This is an odd way to build a convention center — shoehorned into the city, split in three, not really big. That said, there are some advantages. It is close to hotels, restaurants and bars. The first phase (opened in 1988) fronts on the attractive Jim Ellis Freeway Park. And the tripartite nature means you can open a mid-sized convention right as another one is closing, rather than wasting days on move-in and move-out downtime.

As a result of all these incremental steps, tourism is now wagging the dog of Seattle’s downtown. Many of our supposedly civic projects are more properly described as tourist-draws: the central Waterfront Park, with its keystone connection of the Aquarium and the Pike Place Market; the downtown streetcar connector, linking Pioneer Square with the retail core; possibly a third cruise ship terminal wedged into Pier 46 just south of the ferry terminal; the reworking of Seattle Center as a sports venue.

Which leads to the question of how we can tame this beast, and (if it comes to this) what might be a better use of the convention center 3, now one-third built and facing a serious financing problem. Some ideas are floating around for adaptive re-use of what’s called The Summit (CC-III). Use the kitchens to feed the poor. A vaccine factory. A transit hub for buses and light rail. A downtown high school. Housing. A hive for nonprofits, including galleries and theaters. New home for KCTS/Crosscut. Innovation labs.

Just the listing of such more resident-friendly uses prompts thoughts of what it might be like — as rental rates go down, tourism ebbs, foreign investors cool — and the quirky old Seattle shuffles back out of its hibernation to reclaim the city. Just sayin’.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Yes, tourism provides jobs, though it is highly debatable how many of those jobs are year round living wage jobs. And given the huge carbon footprint of airplanes and cruise ships, any serious consideration of global equity demands that we shrink these sectors of the economy as we stare down the barrel of the climate emergency. How might Seattle (and the Port of Seattle) rethink their missions to serve the people who live here rather than continue to invest in mega projects which are highly susceptible to downturns in the economy? In a bioregional based economy, tourism could be replaced a more locally oriented goods and services oriented economy in harmony with the local environment and global responsibility. Seattle can lead the way on this, or fall in line with business as usual. The choice is ours.

If they do manage to finish this project, no one will be using it until it’s an obsolete white elephant. Here’s an idea: demolish it now, before more good money is thrown after bad. $300 million? We all know that’s just a lowball starting figure. We’ll all pay for it, whether it’s through bonds or federal spending. Tearing it down would cost some bucks, but fewer. And the scrap metal might be worth something.

Then leave it as grassy, open space in the middle of the city. No camping allowed. Maybe widen the thoroughfares and sidewalks. Hey, our ancestors tore down Denny Hill. The Washington Hotel people at the summit probably weren’t ecstatic when it happened. The speculators who built the hotels next to the convention center? They’d be on their own. But that’s what speculation is: no guarantees.

The scrap metal might be worth something.

Then use the cleared land for open space. No camping allowed. Open space, with grass, right in the middle of the city. Maybe widen the thoroughfares and sidewalks.

Thanks for this perspective David. It’s time for good ideas to rethink this monster.

Through 2016 and 2107, several of us testified before the Seattle Design Commission on more than one occasion, wrote voluminous memos and met with members of Council. We including not only critique but concrete recommendations about how this could be reconciled with the community in mind, making it an asset to downtown, the region, and neighboring Capitol Hill. All to be greeted with radio silence. The faulty assumptions on which this was sold were transparent even then. Why would no one listen? We have a vision for how to adaptively reuse this white elephant and convert it into a welcoming center in the heart of the city. Anyone interested?

This project cannot be finished as originally designed or purposed. But we do have a need for community and civic spaces in downtown that can help turn it into a real neighborhood. There are ways to reconceive this and make adaptive redesigns to make it an asset to downtown and the surrounding neighborhoods. Yes, the COVID 19 crisis has exposed the folly of some “grand ideas” (time to rethink the aquarium shark tank expansion, for instance) but a thinking person could have known this long ago. If Seattle prides itself on environmental sustainability, it needs to walk its talk. Building these kinds of buildings doesn’t contribute to addressing the climate crisis. The proposed 1-5 lid should be a knuckle that connects Capitol Hill and downtown. A visionary civic facility that is built with community and equity in mind could be an asset to both.