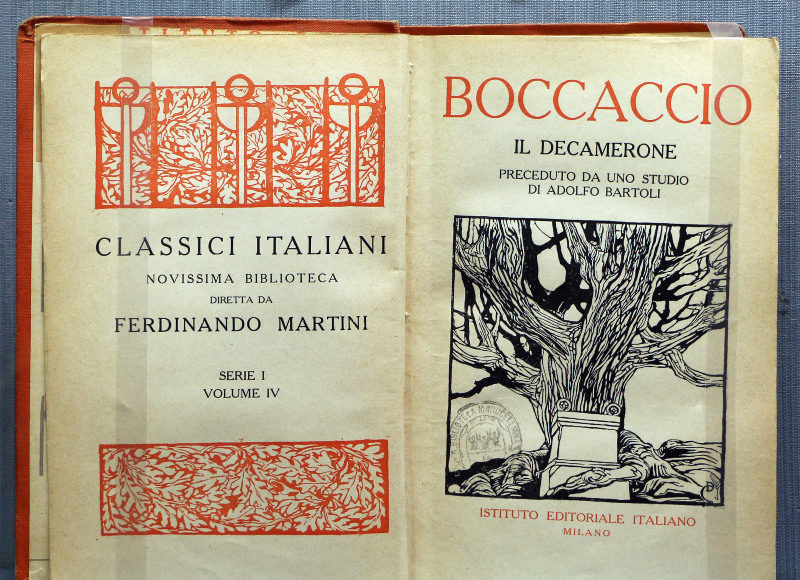

As we shelter in place, now’s a good time to catch up on plague literature. Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, “Ten Days,” set outside Florence during the bubonic plague of 1348, appeared in 1353. Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year describing London during the Great Plague (bubonic) of 1665-6 and based on his uncle’s notes, saw print in 1722. Histories of Seattle’s influenza outbreak from September, 1918, to February, 1919, can be explored on line (and discussed below). Albert Camus’ The Plague, set in the French Algerian city of Oran during a 1940s cholera outbreak (the actual outbreak occurred in 1849), was published in 1947.

All deal with the human reaction to mass death and suffering. In Decameron, seven young women and three young men flee Florence to a villa and spend their time telling earthy and engaging stories. Defoe’s narrative has strikingly modern parallels: the appeal of statistics; the theme of economic inequality which enabled the rich to flee while the poor die; and the debilitating, pervasive fear.

The onset and turbulent passage of Seattle’ influenza epidemic matches our present experience, and its history may serve as a route-guide. The “Spanish” Flu orphaned Emmett Watson and Mary McCarthy who, arguably, became writers as a result.

I am privy to another family’s experience.

Medard (pronounced Mido’r) Emard, a city railway conductor, his wife Catherine and children Louise, Joe, Rose, Catherine, and Margaret lived in Belltown. A light pole-cum-hitching post near their house bore tooth marks left by panicked horses chewing the wood during the great 1889 fire. Louise was ten and Margaret two when their mother became one of Seattle’s 1,400 influenza victims in early 1919.

A literate man, Medard wrote his grief into poetry. Louise was put in charge of her siblings, but baby Margaret was given to great aunt Margaret Duffy to raise. They all remained close, living bare miles from one another. The sisters became buoyant matriarchs of the vast, extended family well into the 1970s.

The deep trauma of their childhoods catalyzed an exuberant love of life, roistering humor, and a profound love of children. Childless, Louise mothered mobs of nieces and nephews until old age. The others raised families as they chatted one another daily on the phone. Catherine translated her grief into poetry and an intense, empathetic gaze that drew children to her lap where they confided their thoughts to her.

I married Catherine’s youngest, Mary Anne, who inherited her mother’s concern for children by becoming a gifted and much-loved teacher. I recall asking her what her favorite moment was when our and her brothers’ families spent summer weeks at Cannon Beach. “When everyone is home safe,” she said.

A horrifying total of 36,000 people died in Florence–60% of the population–during Europe’s first encounter with the black death. In Defoe’s London, 100,000 died from the bubonic plague. Cholera killed 6% of Oran’s population of 25,000 in 1849.

But in Decameron, the ten celebrate being alive. Defoe praises his uncle’s compassion. Camus, a native of Oran and one of the leading existentialist writers, concludes that, despite the plague’s absurdity, there is more to admire in humanity-under-pressure than deride.

In Seattle, what does not kill us can enrich us.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.