Ah, the joy and tragedy of numbers. Oregon Democrats were ecstatic last November when they won super-majorities in both houses of the Legislature by meeting the standard of 60 percent in both chambers. But, alas, it takes two-thirds of members (20 in the Senate, 40 in the House) for a quorum.

Therein lies the rub. And, for Oregon’s endangered Republicans, the precipice.

This past week the Democratic leaders of the Oregon Legislature abruptly adjourned their 35-day session because Republicans in both chambers walked out—and stayed out for over a week—to deny a quorum and prevent the sure passage of a climate-change measure calling for a cap-and-trade policy.

A Republican boycott sidelined cap-and-trade in the regular session in 2019, but a year ago Democrats did not have a super-majority. Now they do. But the “off-year” session had to adjourn in a stalemate because Republicans played the quorum card.

The tactic has precedent in both parties. Democrats used it to delay a redistricting bill in 2001, which eventually passed. I recall a huge flap in the mid-1960s when Democrats walked out briefly after the Republican-controlled Senate refused to bring the 18-year-old vote to the floor. It was a bit of comic opera at the time, key senators flitting in and out of the Capitol. It ended quickly with passage of the bill.

But the impasse is now getting very serious, and threatening real consequences in a state where the Legislature has been traditionally held in general respect. There appears to be a general breakdown in the bipartisan comity that made things work several decades ago. Shared values seem to be in short supply as the urban-rural split becomes a chasm in the new century.

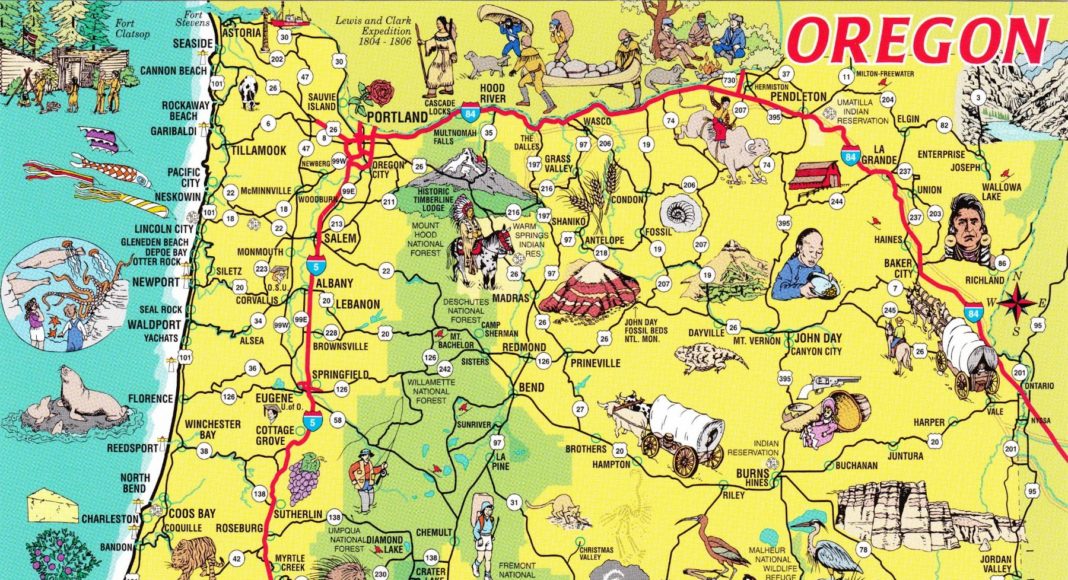

Once again, the numbers. Put simply, Oregon’s growth is almost entirely in the Portland urban area with outposts downstate in Eugene and, increasingly, Bend. Rural areas, dependent on agriculture and timber, have stagnated and the 2020 Census will not be good news for Republicans. Redistricting will further isolate GOP legislators and if Oregon gains a sixth member of Congress, it’s likely to be a fifth Democrat.

Unlike Washington, Oregon now has little political clout east of the Cascades. Oregon lacks population and economic hubs comparable to Spokane, the Tri-Cities, and Yakima. Only Deschutes County (Bend) is growing, in part as an attractive draw for California retirees; but with such growth comes more Democratic voters. Hood River, just east of the mountains, is rapidly gentrifying and growing more liberal.

The math of Baker v. Carr, the 1962 U.S. Supreme Court decision that enshrined the “one-man, one-vote” principle, continues to grind, nearly 60 years later. The 2020 election may give Oregon Democrats not only super-majorities but guaranteed quorums in both houses.

This Tuesday (March 10) is the filing deadline for the May 19 primary, and it will be interesting to see if the two Republican legislators who did not walk out—both are from Bend—will be “primaried” by conservatives. Conversely, some of those who did walk may face opposition. Certainly the session was dominated by raw politics, in the view of veteran political reporter Dick Hughes.

There is an inexorable logic to the Democrats’ refusal to buckle to Republican demands for changes in the climate-change bill or a referral to the voters. It is quite simply that Democrats ran on a promise to act on climate change, and they won. Republicans cannot argue with the numbers—Democrats do hold a huge edge in the state and, therefore, the Legislature. But Republicans made promises as well—and they feel beholden to their voters to use all legal tactics to prevail.

Oregon’s dilemma in some ways dates to the 2010 statewide vote for annual sessions, replacing the traditional biennial session but limiting the “off-year” sessions to 35 days. Among the things that are hard to do in such a short time is negotiate, work on bipartisan coalitions, and bolster the relationships so important in a legislative body. Those relationships can make or break a legislative session.

I had moved away by 2010 so I don’t know what Oregon voters thought they were approving, but my guess is they had in mind something to replace the ad-hoc, short, special sessions that had been growing over the years to deal with emergencies. Massive changes like climate-change or an overhaul of school funding were probably not on their mind. But the measure approving the annual sessions contained no limits on topics.

The irony is that the stalemate may well lead to one of those special sessions, or to an aggressive exertion of executive power by Gov. Kate Brown (D) to enact climate-change measures without legislation.

Democrats, in Oregon and elsewhere, are generally more agenda-driven than Republicans. Urban needs and concerns grow in complexity as a state becomes more urban and more diverse. Republican areas have more traditional needs, and GOP legislators are more driven by allocation of funds and the priorities of transportation and agriculture.

These differences—vastly over-stated here—are likely to pressure urban Democrats to take advantage of a super-majority to push through complex legislation that they understand and believe is critical to the state, particularly its growing urban centers.

Because the balance of power is more equal in Washington, we may not face the specter of walkouts and boycotts in the manner that threatens Oregon. But legislative bodies everywhere—not least the Congress—are terribly torn these days between the priorities and tensions between urban and rural. Worse, they are lacking in ways to bridge the gap.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

For anyone wanting a more complex (and more partisan) view of the Oregon dilemma, check out this Vox post:

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2020/2/29/21157246/oregon-republicans-walk-out-climate-change-cap-trade-democracy

Just as the coronavirus threatens our image, the toxicity of Oregon’s legislative politics threatens Oregon’s longtime reputation as a state of clean politics