On a sunny Saturday in late August of 2019, with the Space Needle as her backdrop, Elizabeth Warren spoke to an adoring crowd of 15,000 Seattleites, the largest crowd of her campaign to that point. The national pundits were suitably impressed, saying that, “Warren is on a major roll — and her ballooning crowd sizes are a reflection of that momentum.” By October the New York Times was declaring her “a clear front-runner in the race for her party’s nomination.”

But by the time the Times, which provided repeated glowing front page coverage all through the summer of last year that helped fuel Warren’s rise, made that declaration in mid-October 2019 signs were already emerging that Warren’s appeal was limited and her campaign was strategically misconceived.

While Warren’s topline poll numbers surged in the late summer and early fall of last year, they masked a sobering reality: her base of support was very narrow. Warren was winning because she was doing extraordinarily well with only one, albeit large and noisy, segment of the Democratic primary electorate: well educated white, cosmopolitan progressives, what political consultants sometimes call the party’s “wine track.”

White college-educated voters compose about 40 percent of the total Democratic electorate; with the other 60 percent – non-college whites and minorities – Warren presented as a culturally alien elitist. That perception was exacerbated by her tendency (more so than any of the other major candidates) to slip into the language and cultural cues of performative white wokeness.

By far, Warren was the candidate most beholden to the narratives set by Left Twitter and the national media. On more than one occasion, she walked back something she had said or changed her position on an issue because left activists complained (for example, here). She ran a branding and messaging effort entirely designed to impress liberal editorial page writers (and political reporters) but which massively failed to connect with the sorts of non-college educated and minority voters who make up the actual majority of the Democratic Party. Even her brand of populism was elitist.

New York Times readers (and reporters, apparently), over-40 progressives living in the Seattle bubble, left activists in general loved her. The African American female grocery store checker with three kids in Greenville, South Carolina? Not so much.

Warren was, at her core, a Twitter and Pronouns Democrat, who pitched herself as a candidate for online left activists to rally around. The national media hammered relentlessly at the lack of appeal to minority voters of another wine-track candidate, Pete Buttigieg. For months, swayed by the size of her (very white) crowds, they ignored that Warren had the exact same problem. Instead the media narrative-setters pushed forward gushing coverage of her rallies and fawning pablum about her willingness to call people and take selfies with adoring fans.

Still, there remain two central questions. Why didn’t Warren, who made educated white progressives hearts go pitter patter, have more appeal with the remainder of the Dem electorate? And why did so many educated white progressives abandon her in the late fall as the campaign wore on?

Yes, part of the answer is clearly that many voters have a double, and more critical, standard when it comes to female candidates, particularly ambitious, successful, middle-aged women. But that’s not the entirety of the answer. After all, if Warren had been able to hold onto the 25 percent support she had at her peak in the September and October polling, she would have done fine once the primary voting started. Instead, she slumped badly and hemorrhaged support as the actual voting loomed.

Now that the her campaign is history, some armchair quarterbacks are saying that the campaign’s exuberant emphasis on her policy wonkishness (she has a plan for that!) served her poorly, pigeonholing her as a cerebral elitist. They posit instead that she should have been putting much greater emphasis on her biography, and her hardscrabble Oklahoma roots, instead.

Maybe so, but it was Warren’s all-in commitment to an orthodox left activist policy agenda (remember, she has a big, bold plan for that) that branded her a cultural cosmopolitan – a candidate to make Seattle swoon – but in a way that alienated her from less educated and less ideological voters wary of fantastical promises of radical change. Personally, I doubt any amount of emphasis on her more modest class origins would have done much to counter that perception.

The breadth of Warren’s appeal was always likely be somewhat limited and narrow, but that wasn’t necessarily fatal. Bernie Sanders has done quite well for himself in this race with the allegiance of a relative narrow minority of the party.

The other factor that came into play was that -– again, contrary to all the media hype — in terms of developing and executing an effective campaign strategy, her campaign team were idiots. They wasted huge amounts of money hiring scores of organizers in post-Super-Tuesday states — for example, they had something like 40 people on the payroll here in Washington State for months — and then spent barely any money on TV in the early states, which were must-win races.

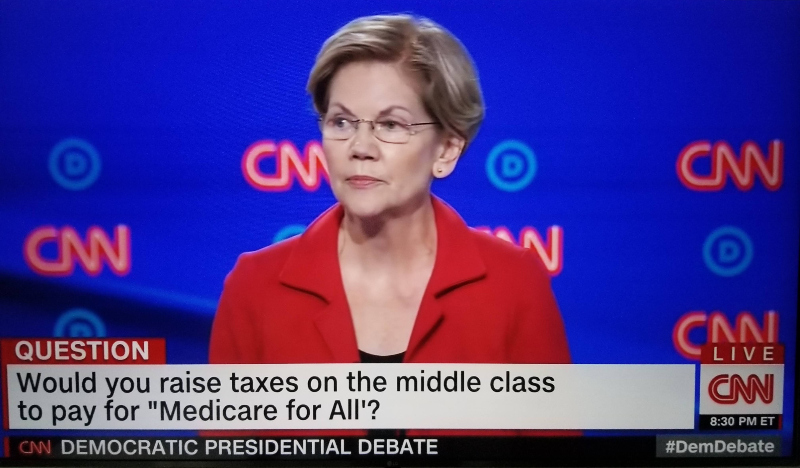

For some bizarre reason, they thought she could just float above the fray to victory. Last September the Buttigieg campaign started running sharp, effective TV ads in Iowa and New Hampshire that called Warren out (though not by name) on her support for Medicare for All and on her enthusiastic embrace of partisan tribalism.

“We will fight when we must fight but I will never allow us to get so wrapped up in the fighting that we start to think fighting is the point,” Buttigieg memorably said in one of them, implicitly but obviously contrasting himself with Warren. She ignored Mayor Pete for weeks as her numbers began to slide. She didn’t really respond to those attacks until November, and by then it was too late. Buttigieg had surgically cut her off at the knees.

Even worse, her campaign made the breathtakingly amateur-hour assumption from early on that the race was going to remain fragmented and contested the whole way to the convention, and that they could survive losing the early states because they’d haul in the delegates later in March. Any good campaign consultant, or anyone who’s looked at the historical record of how these presidential races typically evolve, could have told them that was a major strategic blunder.

It was always very, very likely that the race would consolidate during the Iowa/NH/NV/SC phase and then only one or two candidates would come out of Super Tuesday with the momentum to keep going. (This was also why Bloomberg’s unorthodox Super Tuesday strategy was a complete Hail Mary.) And also that all the “grassroots ground game” organizing her legions of paid staffers had done in cities like Seattle would be washed away by the momentum of the early states’ winners.

That strategy did get her a bunch more foolish and misinformed media hype — there’s so much bad and just plain wrong media coverage of presidential race campaign strategies — about how she had such a great and vaunted national campaign organization. The national media kept hyping that she had the best ground game and the most comprehensive national campaign! So many offices, so many staffers, so she was sure to win!

Then she fell down in Iowa and couldn’t get up, in significant part because she wasn’t on TV making her case. By Super Tuesday, Biden crushed her like a bug in her home state without even stepping foot in it. Biden enjoyed the slingshot momentum, followed by the inevitable consolidation, that happened when he won South Carolina.

Which leads me to the conclusion: if she hadn’t wasted all that money impressing swooning, credulous New York Times reporters with her “organizational strength” in states that didn’t matter she might have been able to actually win one of the ones that did.

In the late stages of the campaign, after the more polarized movement-left portion of her educated white progressive base had already dropped her for Sanders, Warren tried a major messaging shift by suddenly portraying herself as a consensus candidate, one who could knit together the moderate progressive Obama wing of the party with the left activist AOC wing. This is also what she told reporters as she dropped out of the race, lamenting that she had sought to find a middle ground between the two divided camps, only to discover that wasn’t possible.

But this attempt to portray herself as some sort of martyr for party unity is extraordinarily tendentious, revisionist history. Until the final weeks of the race, Warren ran as an uncompromising left activist fighter, not an Obama-style uniter. She presented herself as the more likeable, less angry, and more electable version of “beer track” Bernie — a leftist without the anchors of the “socialist” label and the online army of off-putting, dirtbag-left zealots.

Warren wanted to be seen as a “big structural change” activist, but one with the cultural fluency to win over the affluent, cosmopolitan, professional class. She offered nothing to moderates, nothing at all, other than that she wasn’t Bernie. Even her idea of minority outreach was about making ultrawoke promises that were designed to win her the support of highly educated, highly polarized identitarian chattering-class types, rather than saying things that would connect with actual minority voters in states like South Carolina, Virginia, or even her home state of Massachusetts.

In the end, Warren did to herself and to her campaign what Kamala Harris had done before her: she mistook Twitter, and the New York Times editorial page, and (the biggest political misjudgment of all) affluent, white, progressive Seattle as the authentic and representative voices of the Democratic electorate writ large. And like Harris before her, she paid the ultimate price for that mistake.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

It may be that the media fixation on Warren blinded the public to the more thoughtful positions of Amy Klobuchar. The two obviously did not get along, and Klobuchar bridled at the Post-It putdown that Warren stung her with, over her health insurance plans. Here’s an article making this argument, as well as dissecting the weaknesses in the Warren campaign. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/03/07/actually-elizabeth-warren-is-not-candidate-mourn/

I also liked the Stephen Stromberg piece in the Post and would have voted for Klobuchar if she remained in the race. Both in her debates and in her powerful endorsement of Biden, she showed campaign power to go with her strong record in Congress.

Unlike Warren, Klobuchar will still be “middle age” four years from now and if Biden picks her for his ticket, she would be vice president. Democrats cannot continue to ignore the middle of the country when picking a ticket. Biden needs a strong woman on that ticket, one who can help in the Midwest and who also has the chops to help him govern.

I’ll be very surprised if Biden doesn’t pick an African American woman — Abrams or Harris, perhaps? — as his VP nominee (assuming he gets the nomination). He and his strategists know they need to do two big things to win: shore up his left flank, and boost African American turnout in key swing states. Putting a woman of color on the ticket would help to accomplish both tasks.

Picking a strong moderate like Klobuchar would be perceived as Biden giving the finger to the party’s alienated and restless left wing, something he probably can’t afford to do in November if he is going to consolidate the party enough to win. So while I like Klobuchar too, and undoubtedly there’s be a significant senior role for her in Biden administration (assuming she wants one), I don’t see her as a very realistic VP nominee for him.