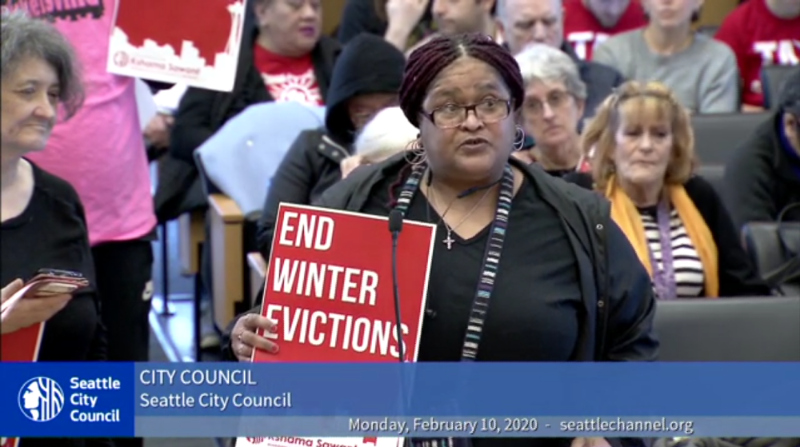

Seattle’s City Council has banned renter evictions during the winter. The legislation, which passed unanimously on February 10, is not a total ban and it will not end homelessness. However, it will give renters the ability to stall evictions from November 1 through March 31. The goal is to prevent mostly low-income and people of color from winding up on the street if they cannot pay their rent during the coldest and wettest months of the year.

Councilmember Kshama Sawant, the sponsor of the legislation, said it was a “humane approach to the homelessness crisis that voters have called for.” This echoes a major theme of every candidate elected to the council last November – we must not abandon those who are homeless.

Evictions that push renters out of their homes are most often due to economic hardships. According to a study by the Seattle Women’s Commission and the King County Bar Association’s Housing Justice Project, Seattle experienced 1,218 evictions involving nearly 1,500 people in 2017. About half owed one month’s rent, with a median rent for those evicted of $1,250 or less.

Seattle’s legislation goes beyond providing what a few other cities do to help renters from being evicted. For example, New York and San Francisco guarantee the right to legal counsel during an eviction. While Seattle has offers low-income incarcerated people access to legal aid, it does not guarantee a lawyer for people facing eviction. In Washington D.C. the US Marshall Service will not complete evictions when precipitation is falling or when the temperature is forecast to fall below 32 degrees Fahrenheit that day. The eviction will be completed on the next available date on which the temperature and precipitation permit. It is a humane approach, but hardly a solution to stopping or even reducing evictions.

Seattle’s legislation breaks new ground. Rather than starting from scratch to write a new law, the existing Just Cause Eviction Ordinance was amended, which already prevented landlords from arbitrarily ending rental agreements. The legislation doesn’t prohibit evictions but provides a new legal right to defend against an eviction. A memo from the city council’s staff said a tenant or their attorney could raise a legal defense in response to the landlord’s claim for the right of possession during the eviction proceedings in Superior Court. Presumably a judge would either rule in favor of the tenant and the landlord could refile a complaint to obtain possession after April 1; or the judge will simply delay execution of the writ of restitution until after that date.

Two factors allowed for passing this legislation. One is Seattle government’s infrastructure, which empowers its residents to influence public policy through citizen-run commissions. The commissions allow citizens to see politicians as possible allies in pushing for structural changes that are not tied to contributing to their reelection campaigns.

Seattle has a robust array of citizen commissions that have helped shape legislation. It’s important to understand how citizen commissions need are formed and operated so that they don’t become mere window dressing.

Generally, a city council has the authority to introduce legislation creating a citizens’ commission on any topic it wishes. It can define who is on it, how they are appointed, and what their focus should be. The mayor would usually have the power to approve or veto such legislation. But the council can initiate its creation and it can also allocate funds for staffing the commission.

The Seattle Renters Commission is an example of how a citizens’ commission was created and how it initiated the ban on renter evictions. The ordinance creating SRC was unanimously passed by the Seattle City Council in March 2017, with the most progressive and conservative council members co-sponsoring it.

Seattle has long been a city dominated by single-family neighborhoods. With 136,000 people moving into the city from 2010 to 2018, by the end of that period 48% of its residents were living in rented units, whose rents had dramatically increased. Zillow tied these rent increases to a rising homeless population, estimating that Seattle’s homeless population was the third highest in the nation by absolute number.

Renter concerns in general were not being represented on the city council, which traditionally had no or only one renter as a member. Renters have different public needs than homeowners, particularly since the median income for renters is less than 50% of homeowners in Seattle, according to the US Census Department. Consequently, councilmembers concluded that having a renters’ citizen commission to weigh in on city policies and guide legislation.

The SRC has 15 members, six appointed by the council and six by the mayor, with two selected by the commission and one youth appointed to fill a slot saved on every commission for such a person. It’s important to divide the number commissioners appointed so that both the mayor and the council have a direct connection to its membership. A commission’s composition should be determined through the legislation. In SRC’s case, appointees must represent varied perspectives that reflect historically underrepresented groups like the low-income, LGBTQ, immigrants, former felons and those who had been homeless. The city’s Department of Neighborhoods funds staffing for the commission.

All of SRC’s characteristics described above are similar to the other citizen commissions that have been established. All of them have a councilmember who has direct oversight of their operations, all have city funding for staffing, and all have open public meetings. Their members have set terms and are uncompensated. Their effectiveness is determined by their own leadership and by the willingness of councilmembers to work with them to promote an agreed upon legislative strategy.

This is what happened when the SRC wrote a letter to Councilmember Sawant urging her as chair of the council committee overseeing renter concerns to support a renters’ eviction ban. The letter advised: “Passing such a moratorium will keep neighbors from being displaced to the streets during the months with the harshest weather and poorest living conditions for neighbors living unsheltered.” Nearly 52 percent of tenants who faced eviction in 2017 were people of color, with a high portion of them being black women. In response, Sawant agreed to bring forward legislation to put a ban into effect.

The second critical factor in passing the eviction ordinance was having a councilmember who is willing to support the legislation and to actually work with citizens and other councilmembers to get legislation passed. Citizens need someone who knows how to work the labyrinth of laws and who can mobilize people outside city hall.

In this instance, Sawant worked with those inside city hall to expand the coverage of an existing law. While she opposed all but one of the amendments that were made to her legislation, she did not withdraw her support from it. She recognized and celebrated its passage as a tremendous victory for Seattle’s renters. Sawant also organized directly with community-based organizations to have supporters appear at the city council’s chambers to testify and visibly show that the legislation was of immense concern for many residents.

Other councilmembers played a critical role in proposing constructive amendments and supporting the legislation as a whole. Unlike the candidates who ran and lost in the most recent city council elections, they did not oppose legislation because it regulated the private market.

Seattle’s eviction legislation may seem like something that could only happen in Seattle. However, it could be adopted in other cities if they develop government portals to involve direct citizen participation in policy issues and have elected officials who can be organizational leaders. Progressive solutions are not arrived at spontaneously. It takes a road map to reach them.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I believe one of the passed amendments narrowed the no-eviction window to December 1st through February 28th. Otherwise, a very interesting article on the background of the legislation; I learned much I did not know. Thank you.