I like to teach ancient thought at Seattle University because I find it so completely relevant. Hearing this, one audience member asked me, “Well, then, what would Plato have said about Trump?” “Oh, Plato had a lot to say about Trump,” I replied.

Trump is a political type of ancient origins, a phenomenon as old as politics itself, figuring prominently in the earliest debates over the merits and demerits of democracy as a form of government. On that phenomenon Plato wrote at length and in powerfully dramatic detail.

The type is the demagogue, the man of the people (demos), who presents himself as the champion of the desires of ordinary citizens, however unrealistic or politically incorrect his expression of those desires may be. The demagogue appears to be the best friend of people of common sense, drawing fierce loyalty from the persuaded among them. Yet a pejorative connotation has always attached to the word, “demagogue,” because leaders of this type have so often used their powers with deliberate deception and for their own gain.

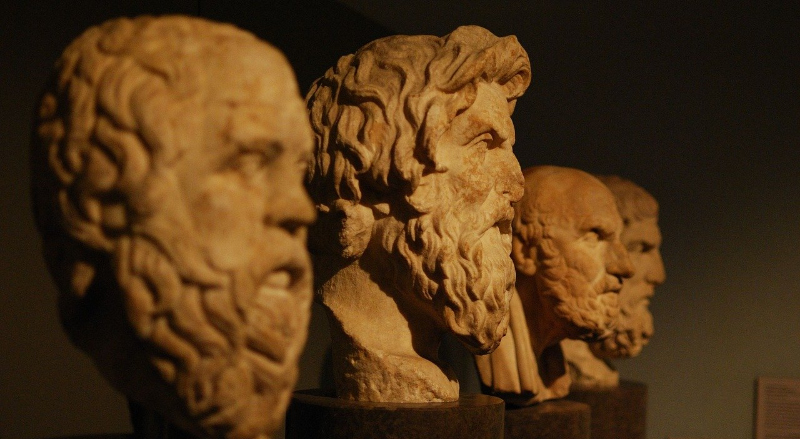

Plato had a philosophical fascination with demagoguery because of what it reveals about the role of truth and untruth in governance. The problem with untruth is that it is so often more convincing than truth; the problem with truth is that it is so difficult to obtain that the honest among us must admit that we possess very little of it. The philosopher, Socrates, was a hero to Plato because he steadfastly took the latter path, admitting to his ignorance as the first step toward an arduous search for truth.

But many of Socrates’ conversational partners, as they are recreated in Plato’s Dialogues, are fans of the kind of political oratory that is measured in its success in persuasion rather than its veracity. The character, Meno, in the dialogue that bears his name, tells Socrates that his many public speeches on the topic of virtue have been well received. Then, with just a few questions Socrates reveals Meno’s opinions to be a mixed bag of popular prejudices, devoid of any real reflection on the meaning of the word, “virtue.”

Characters such as Meno, or Callicles in the Gorgias dialogue, or Thrasymachus in the Republic, judge oratory by its success in winning adherents because their goal is not understanding but power, especially the kind of power which, unchained from the constraints of truth, may be exercised however they wish.

We know Plato’s point best from his famous allegory of the cave, where puppeteers cast shadows on a wall before prisoners, who think the shadows real because they have never seen anything else. If we imagine a prisoner who has been released and who, after seeing the light of day, returns to the cave to share this wonderful news, we know that his announcement will be ill received. People will cling to the shadows in the name of truth because the truths of the world of light threaten everything they know.

Alongside Plato’s concern over demagoguery stands his preoccupation with the question of expertise. His fellow Athenians, he noticed, were inclined to believe that if a person were an excellent speaker, or warrior, or property manager, then that person must be “wise,” and therefore qualified for the tasks of governance. But in Plato’s Apology, Socrates characterizes his life’s work as a systematic questioning of such authorities, showing their knowledge to be limited to the areas in which they were trained. There is no reason to expect that their expertise would somehow automatically spill over into the realm of public policy.

Indeed, the problem goes deeper: it is a matter of the formation of character. Not only our skills but our moral sensibilities are forged into stubborn patterns by the communities and social systems in which we participate from an early age. Hardly any such systems in Plato’s day sought to form a character equal to the immense challenges of governing. His Republic indulges in an extended fantasy, full of exaggeration and satire, of what an uncompromising education for leadership might look like. But even in this highly controlled situation it is acknowledged that only some students will emerge with the requisite character and skill.

Plato did not see demagoguery and lack of expertise as failures of Athens to properly institute democracy; they are weaknesses inherent in democracy itself. In democracy, leaders are accountable to voters who are accountable to no one and who can vote according to whims and illusions as easily as responding to reasoned arguments. The system is perfectly tailored to demagogues, the best of whom know how to get the demos to vote their democracy out of existence.

Such inherent weaknesses have historically formed the heart of conservative critiques of democracy, grounding a preference for systems where representatives are held to accounts beyond those of their constituents. Such weaknesses are the reason the founders of the U.S. government (steeped, as they were, in knowledge of the ancient world) tempered their democracy with a written constitution, the use of representatives, and the separation of powers.

And yet one does not hear such apprehensions in the rhetoric of the people who champion the reign of President Trump in the name of conservatism. They express complete confidence that success in the world of business qualifies one for leadership of a democratic republic, even as corporate governance structures differ in obvious and substantial ways. They tolerate Trump’s epic oratorical spectacle of hucksterism and lies because these feed so magnificently the illusions of the most fervent among their constituents.

Those of us who are alarmed by Trump and his disciples, as we denounce the President’s attacks on science, his moral failings, and his degradation of political discourse, share a Platonic worry that what the Trumpians deem a minor surrender of truth for the sake of major goods is really a major surrender of truth: an embrace of the view that truth is simply whatever you can get people to believe, whether by persuasion or force.

Yet Plato would want those of us who denounce Trump to also take stock of our own relationship to the truth, pondering how much we have tolerated the shadows that parade across the electronic cave walls in our living rooms, how much we have depended on puppeteers pandering to our own tastes to deliver reality to us.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.