A language dies when it is no longer spoken. We live in a region where the language of Native Americans is barely alive. English predominates as does Spanish, the oldest European language spoken here. Prior to American settlement in the 1850s, a few hundred fur company employees spoke English. More of them spoke French, and some spoke Gaelic. But before English became predominant, hundreds of thousands of native people spoke their own languages. What happened to these native languages?

They were erased. Americans forced native people onto reservations to be assimilated into American society. Children were taken from families, put in reservation schools and taught to read, write and speak in English. There, native languages were forbidden and speaking in one was punished. As native speakers died, descendants lost the ability to speak their language. E pluribus unum, the national motto derived from one dead language, portended the death of others.

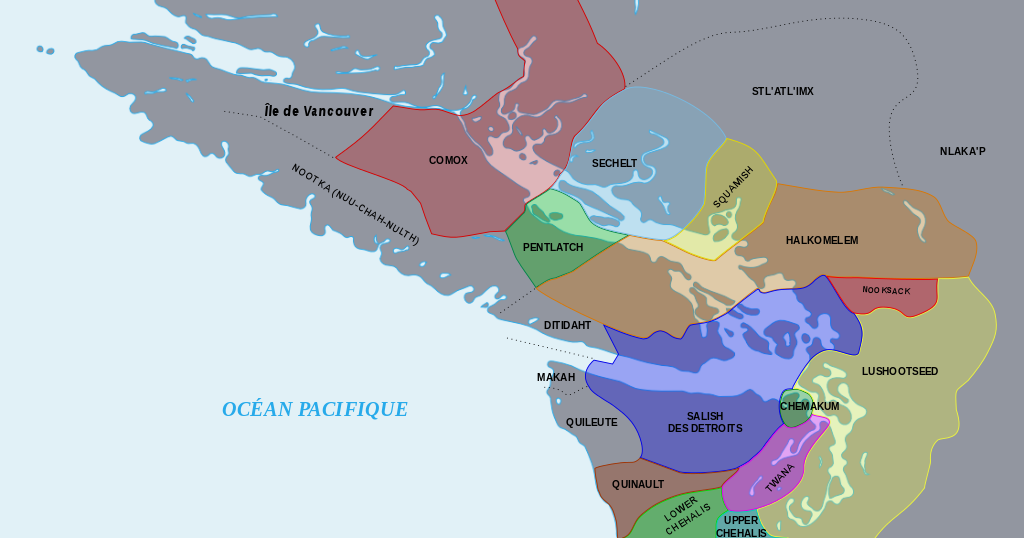

Paradoxically, suppression of native languages was accompanied by efforts to understand them. To proselytize more effectively Catholic and Protestant missionaries learned them and produced native dictionaries and grammars. Gabriel Mengarini, S. J., an Italian Jesuit, became so fluent in the Saleesh language of western Montana that native contemporaries said he could not be identified as the non-native speaker. His work led to the identification of the Salish language family, of which Puget Sound Salish is a distinct form. Starting in the 19th century, anthropologists, linguists, and native speakers such as the late Vi Hilbert carried on the work.

Because so few local native people remain fluent in their historic speech, these rich languages now are taught in reservation schools and universities. Professor Nile Thompson has spent decades working on a dictionary of the Twana language, a Puget Salish dialect spoken on Hood Canal. While some work, he says, had been done with Puget Sound Salish dialects, more was done with Twana. Interestingly, the modern name for Puget Salish, Lushootseed, comes from Twana: “lush” meaning chopped up and “utseed,” meaning from the mouth. Twana speakers said spoken Puget Salish sounded “all chopped up.”

Language has phonological and phonetic aspects. Phonology, the science of phonemes, studies the system of sounds children absorb to distinguish meaning; it is in the brain. Phonetics studies what comes out of the mouth. A person is fluent when they master both and are can express themselves fully to fellow speakers, and most children are functionally fluent in their native tongue by age four or five. Words are made of sounds — consonants and vowels in English, and the modern Puget Salish alphabet has forms to signify glottal stops, glottalizations, whispered sounds, and others unfamiliar to the ears of English speakers.

Languages also have unique syntaxes, the way words are organized into sentences. In Puget Salish pronouns often follow predicates, and phonemes are arranged in unique ways to transmit meaning. Generally Lushootseed sentences follow a verb, subject, object order and tend to be agglutinative, as a large number of morphemes (in English: the prefixes for / fore) and suffixes: ed / ing / tion) are available to change meaning and action. Sentences may have no verbs but rely on context for meaning, such as “singing [occured],” There are also no linking verbs: in English “Who is that?” can be written as “Who that?”

As with other foreign languages, older students of Puget Salish languages often find the rules governing their syntax challenging and the languages’ exotic sounds difficult to master. When I ask native listeners how my pronunciation of native words is, they are kind enough to answer, “Not too bad.”

Latin and Sanskrit are considered dead languages because, while they are still studied (Latin is still used in science), the societies that produced them survive only in their extant literatures. Ancient Hebrew became a modern, living language because most Jews studied Torah, Talmud, and Mishna in Hebrew, and broad fluency became part of Zionism. Irish Gaelic survived in the Gaeltacht, areas where it continues to be spoken and remains vital in an independent Ireland.

When a language’s last living speaker dies, it becomes extinct. It is forecast that 50 percent of all living languages will become extinct by the end of the 21st century. Puget Sound Salish hangs on by a thread. According to Thompson, because surviving records of Puget Salish are muddled, work on Twana is crucial because a more accurate record of it exists.

Unfortunately, when a language dies the ways its speakers experienced the world vanish with it. In our region, luxuriant landscapes that early explorers could not imagine existing “without the hand of man,” were the product of long human activity. Supposed “virgin” forests were created by human action. Abundant fisheries were well managed. Lush mountain meadows were made that way by constant use and nurture.

Now we are left to wonder what thought leads to such beauty not just being preserved but created. What attitudes of mind and heart, what visions bring it into being? What does it mean to live in such a world? Such unique learning and meaning survive in native languages now at risk and almost extinct. As they disappear, we inheritors of the native land shall all be much the poorer.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.