I’d like to tell a timely tale that happens to be an old family story. It concerns my father’s father’s side of the family, one member in particular, and what his brief career fighting on behalf of Italian immigrants says to us today.

My grandmother’s family was Toscana, from the province of Massa-Carrara at the far western corner of Tuscany. She married a member of a Napolitano family with a calabrese last name, Edward Scigliano — my grandfather by blood.

Eddie Scigliano and his brothers had a head start in Boston’s North End, the city’s oldest, most crowded, and probably poorest neighborhood. More than 20,000 Italians and a smaller number of Jewish immigrants had replaced the Irish, who came earlier and moved on from the tenements as soon as they could. Eddie’s father, Gennaro Scigliano, arrived early in America, in the 1860s, after being displaced by the civil conflict of the Risorgimento. He established himself before thousands of later arrivals began struggling for foothold. Gennaro opened what Americans then called a “pork shop”–a salumeria. It grew into a general food and wine shop, then added a saloon–a sort of informal community center, just the place to launch a political career.

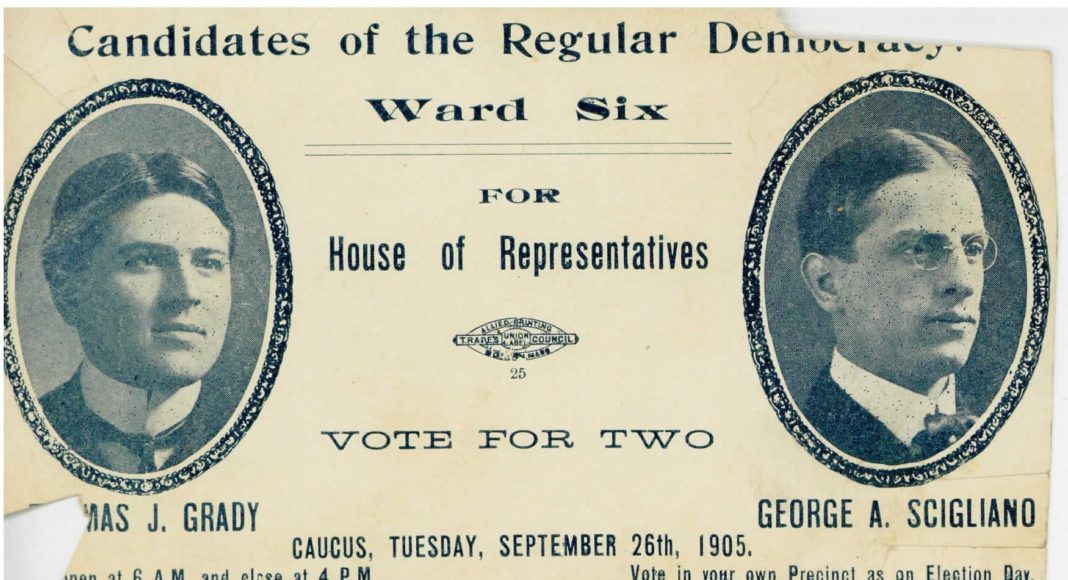

That’s just what one of Eddie’s older brothers, Giorgio Achille Scigliano, did. In 1900, at the age of 26, George earned a law degree at Boston University and got himself elected to the common council, the lower house of Boston’s city council–the first Italian to win office there. To gain that seat he had to attract Irish, Jewish and other voters as well; three-quarters of the North End’s Italians had not become citizens and weren’t eligible to vote.

George Scigliano appealed broadly enough to get elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, another first, in 1904. There he continued to serve a wider constituency, fighting successfully for insurance industry regulation and to reclaim public shorelines from commercial squatters and open them up to the public. But he also became the Italian community’s foremost defender and champion.

That community needed all the defending it could get. About 80 percent of Italian immigrants in America, and an even larger share in the North End, came from the oppressed and impoverished South. They had much lower literacy rates and earnings than German, Swedish, Irish, and Russian/Jewish immigrants. In 1905 in the North End, their average household income was just $338 a year. The district led the city in deaths from typhoid, diptheria, pneumonia and meningitis, and in deaths of infants and young children. It was a hotbed of tuberculosis.

On top of, and because of, the immigrants’ poverty, isolation, and unfamiliarity with a new language and legal system, they faced rampant exploitation by crooks and cheats from their homeland. Padroni, labor contractors, often from immigrants’ home villages or regions, would meet them as they arrived, sometimes right at the boat, offering jobs and housing. Then the padroni signed them up for what amounted to indentured servitude doing pick and shovel work all across the country, on railroads, streets, bridges, skyscrapers, sewers, and farms and in mines. The padroni took fees up front, a share of each paycheck, and profits from the overpriced groceries the workers were obliged to buy from company stores. When the workers did manage to save some money, storefront immigrant banks, unregulated and unsecured, were glad to hold it for them—for no interest and with no security.

Representative Scigliano introduced bills to ban the padrone system and shut down the fly-by-night banks by making them post bonds to indemnify depositors. The padrone bill passed to wide acclaim, and may have served as a model for other states. The immigrant banking bill drew more opposition—from the big downtown banks, who would also have to post bonds and endure more oversight. It passed only after its author’s untimely death, a memorial to his career.

George Scigliano didn’t just battle the crooks and swindlers in the legislative arena. As president of a vigilance committee called the Italian Protective League, he chased them down in the streets. One day, soon after he filed the anti-padroni bill, he got word that a particularly brazen padrone had set up a table in the middle of Old North Square and announced he had a thousand cushy jobs to offer in Providence, Rhode Island. All you had to do was pay a “registration fee” and carfare. Scigliano contacted friends in Providence and verified that the promised jobs were bogus. Then he rounded up some police officers, swept down and busted the huckster, and set about returning the hundreds of dollars his victims had paid.

In 1905 George Scigliano represented Massachusetts at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland. He returned to Boston with a message that can be summarized as “Go west, young Italian! ”—emigrate once again, leave the squalid tenements of the East and come out here where the air is sweet with freedom and opportunity.

Back home, he was esteemed in both the tenements and the wider community. But for the great mass of ordinary immigrants, struggling to scrape by, respect was much harder to come by. They faced scorn and resentment even from the Irish, their nearest neighbors and often their competitors for work, who’d faced the same resistance when they arrived a few decades earlier.

It was an instance of this scorn that first catapulted George Scigliano to prominence. Debate was raging over whether to continue to exclude Chinese workers from citizenship. George Hoar, the senior U.S. senator from Massachusetts, was famously enlightened, a dedicated defender of the rights of Asians and African and Native Americans. He deplored the anti-Chinese policy because it “excludes persons however fit” to become citizens “because of their race or because they are laborers.” An admirable sentiment, but Hoar justified it with an invidious comparison: “The Chinese who is in every respect fit for citizenship is excluded, while the Portuguese or Italian who is in every respect unfit is admitted. “

George Scigliano, a lowly common councilman in Boston, promptly shot back. If Hoar had merely urged fair treatment of Chinese immigrants, Scigliano declared, “we, the people of another race, would not take issue with him. But why, in espousing the cause of one people, should he condemn another?” He continued on a note that’s uncannily familiar today: “While some of ‘the better classes’ do not rightly appreciate the services rendered by the Italian emigrants who are now coming to this country, it is known and admitted everywhere that these emigrants by force of poverty are compelled to accept the cheapest tasks and do the drudgery from which there is as yet no mechanical relief….

“The conditions being equal, the Italian emigrant, as well as the Portuguese, maintains as high a degree of citizenship as the emigrant from other countries. [Treat them] courteously and justly and they will very soon take cognizance for our democratic form of government and become docile, frugal and thrifty citizens, eager to educate their children, who whether in America or in Italy or in Portugal, stand shoulder to shoulder and rank every bit as high as the children of other nationalities.”

Trim the flowery language and substitute “Mexican” and “Central American” for “Italian” and “Portuguese,” and George Scigliano could be speaking to our own overheated times. In his day, Italy was the largest source of immigrants to this country, and Italian immigrant labor was nearly as important to the economy’s functioning as Mexican immigrant labor is today. But this meant that Italians were the visible face of immigration, the terrifying “other” for people whose notion of “American” was white, Protestant, and of North European descent. And they fell into a deep well of anti-Catholic prejudice in America, a form of bigotry promoted by the No-Nothings before the Civil War and the Ku Klux Klan afterward.

Italians were the targets of the same myths and slurs that dog Latino and Muslim immigrants today. In 1891, what may be the largest lynching in U.S. history took place in New Orleans—and the victims were all Italian. After the city’s police chief was assassinated, 11 immigrants who’d been either acquitted or never even charged with the crime were dragged from the jail by what the New York Times called a “highly respectable mob” and shot. The local newspapers and business leaders praised this massacre. Teddy Roosevelt said it was “rather a good thing.” “Lynch law was the only course open to the people of New Orleans,” the Times concluded. John Parker, who helped organize the lynching, went on to become governor of Louisiana.

George Scigliano fought nearly as hard against this sort of slander and stereotyping as he did against the predators within the community. He was one of five “representative Italians” to whom the Boston Globe put what was considered the burning question of the day: “Is the Italian more prone to violent crime than other races?”

“No!” George answered. And when they did commit crimes, even terrible ones, he argued, it was not because of some inherent violent nature, but because of the wretched poverty and crowding, the brutal labor alternating with desperate unemployment, in which they lived. “Where on this earth can men, be they Irish, German, Spanish or italian, meet conditions such as they and live all times and in every way within the law?”

Researchers have since pored through court records and found that Italians were not arrested or convicted at any higher rate then than the general population. What was true then is even more true today: immigrants, Mexican and otherwise, have lower crime rates than native-born Americans. It was true out here as well. In 1915, a University of Washington student named Nelly Roe studied Seattle’s Italians and found that they had lower rates of arrest and conviction than any other ethnic group except the Japanese. She also found that, self-reliant and mutually supportive, they very rarely went on the public dole.

George Scigliano’s reputation for defending the community reached all the way back to Italy. In 1906 he was one of two Americans knighted by Italy’s King Umberto; the other was Harvard’s president, Charles Eliot, an educational reformer who welcomed Catholics and Jews to to that Boston Brahmin bastion. Back home, George’s campaigns against the criminals who did haunt the North End inevitably made him a target, at least of threats. In 1904 he was one on a list of men, including two policemen, that the newspapers reported were marked for death by “la Camora.” His response to threats was bold, even brazen: he published them in the papers. When Boston’s mayor, John Fitzgerald—Honey Fitz, John F. Kennedy’s grandfather and namesake—tried to squeeze him for a bribe, a diamond ring, he took that to the papers too.

We can only guess whether all these threats, and all the enemies he made, had anything to do with what happened next. In 1907 George Scigliano suddenly took ill, took to bed, and died, of what was variously reported to be kidney disease, Bright’s disease, a severe intestinal blockage, and overwork. He was 31 years old.

His widow would not allow an autopsy and insisted that he buried in Worcester, where her family lived and he had gone to convalesce and had died. Nevertheless a funeral service was conducted for him. According to news reports it was the largest funeral in the North End’s history: local businesses shut down, and as many as 5,000 people attended.

The Common Council promptly voted to rename Old North Square, at the heart of the district, “Scigliano Square.” But this gesture became a cause célèbre, as outrage and condemnation drowned out the mourning. Old North Square, where Paul Revere’s house stood, was a landmark of the Revolution, albeit a neglected one; the Revere house at the time housed a barbershop and an immigrant bank. The Sons of the American Revolution and other patriotic groups protested loudly, and the newspapers had a field day mocking the idea of an Italian name for a colonial site.

All this was too much for Boston’s mostly Irish politicians. Honey Fitz denied supporting the change, and the Board of Aldermen voted to reverse it. Soon after, the Revere house was saved, restored, and opened as a museum. You can still visit it today.

The Italian community then called for a somewhat less controversial memorial: to rename North End Park, a larger but less prominent patch of ground, Scigliano Park. The common councilors and aldermen approved this, but the city administration filed the resolution away and never acted on it.

No physical trace remains in the North End of the man who was its most celebrated resident since Paul Revere. In the end, George Achille Scigliano suffered the same official neglect and mainstream disdain as the struggling immigrants he worked to defend.

That disdain continued for many more years. Even as crossover figures were finding mainstream acceptance, an anti-immigrant backlash was already building. Racial purity, and dire warnings about how intermarriage would ruin the genetic stock, became new watchwords.

This supposed true white race pointedly excluded Jews, Greeks, Serbs, Turks, Poles, Czechs—and Italians. They—we, our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents—were on the wrong side of the racial divide. That divide gained the force of law when Congress passed and President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924, spearheaded by a congressman from Washington State named Albert Johnson.

It effectively banned immigration from Asia and Africa and codified a system of national quotas that pegged the number of immigrants allowed from each European country to the number who were already in the United States in 1890—just before the great wave of immigration from southern and eastern Europe. As a result, 55,000 immigrants from Germany were allowed each year, but only 4,000 Italians—down from 210,000 a year just one decade earlier.These quotas were loosened in 1952 and eliminated in 1965.

Now, however, we have a president who is taking us back to 1924. He talks about wanting “more people from countries like Norway” and about keeping out people from African and Caribbean—well, you know what he called those countries. He describes Mexican immigrants in terms that strikingly recall the slurs cast on Italians 120 years ago: Mexico is “sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with them…. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

His administration is doing by fiat and bureaucratic obstruction what was done by law in 1924: reducing the flow of refugees and legal immigrants to a trickle. It admitted fewer than 23,000 refugees in 2018, down from 85,000 in 2016, and plans to reduce the flow to the lowest level since Harry Truman inaugurated America’s refugee program. President Trump has talked about excluding refugees entirely.

Today, however, Italian Americans are not the despised outsiders. We are the “you” the president speaks to, as though we’re his peeps. “White” has replaced Aryan, Teutonic and Nordic as the racialist term of choice, and Italian Americans now find themselves safely on the white side of the racial dividing line. As late as the 1960s, there was an unwritten rule excluding attorneys with Italian names from the big New York law firms. Now two of the last ten U.S. Supreme Court justices appointed—and two of the most conservative–have been Italian. The one still serving has been solidly supportive of the president’s immigration measures. The acting Director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, who once compared admitting immigrants to protecting rats and revised Emma Lazarus’s Statue of Liberty poem to replace the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” with people “who can stand on their own two feet”–is a man named Ken Cuccinelli.

But however the goalposts may move, the game remains the same. Other groups now face what our grandfathers and grandmothers faced—and worse. In these times, I like to ask, What would Uncle George do? As we try to sort through the overblown claims and overheated rhetoric of today’s immigration politics, we have a deep obligation, to the present and to the past, to remember that, there but for a few decades of assimilation, go you and I.

This essay was drawn from a keynote address at the Festa Italiana Seattle luncheon, hosted by the Italian Club of Seattle at the Seattle Yacht Club on September 20, 2019.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A timely and well written piece – thanks, Eric. Nice to read you in PA!

Eric,

George Scigliano was my great grandfather, his daughter Jessica was my grandmother. It was nice for my children to learn more about their heritage. Thank you for this article.