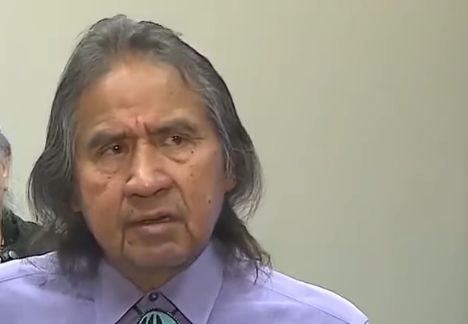

By all accounts native Winnebago Frank La Mere was a remarkable man. Son of a combat veteran and a gold-star mother, his older brother was killed in Viet Nam, his sister died in a hit-and-run, and he lost his own daughter, Lexie, to leukemia. But he transformed sorrow to activism in the early American Indian Movement in the 60s when, only 22, he was selected to present the Bureau of Indian Affairs a petition demanding reform.

For decades he fought liquor stores in White Clay, an open sore bordering the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The reservation banned alcohol; White Clay’s beer dealers sold 13,000 cans a day, 4 million a year to ravaged Native Americans. Principled and tough, La Mere made officials uncomfortable, saying “there’s no point in sugar-coated conversations.” In 2017, beer sales were banned. Lank and gaunt, he appealed at meetings to rapt audiences to “do what you can.”

Chairman of the National Native American Caucus and seven times a delegate to Democratic National Conventions, La Mere died of cancer at the age of 69 on June 17. In August, Four Directions, founded to enfranchise native voters, held the two-day Frank Le Mere Native American Presidential Forum in Sioux City, Iowa. Navajo independent candidate Mark Charles set the tone: “We the people has never meant all the people.”

Eight Democrats including Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren addressed native groups from New Mexico to Massachusetts. No Republicans, but the forum invited President Trump. All agreed the United States must honor the 370 treaties it made with native groups from 1778 to 1872. The forum also asked indigenous academics, leaders and activists what this would mean. Dr. Cutcha Rising Baldy of the Hoopa Valley, Yurok and Karuk people in California said, “If we honor the Constitution, we must honor the treaties.”

Historically the American government treated native populations as wards, legal incompetents to be forcibly relocated and assimilated in government schools, ignoring promised services by pleading economy. Karen Driver of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa argues that “the federal government needs to fully fund its obligations that were pre-paid by tribes with land.”

Regarding treaty rights to hunt, fish, and harvest, DeLessin George-Warren of the Catawba Nation points out that tribal members are regularly fined for exercising these rights, “and the US and corporations continue to build infrastructure that disrupts our ability to practice our traditional food systems.” The Keystone XL pipeline in the northern plains comes to mind.

Northwesterners recall violent fishing disputes between native groups and the state of Washington addressed in the 1964 Boldt decision dividing the catch. Local native leaders like Bernie Frank, Robert Satiacum, Frank Sohappy and Ramona Bennett played roles akin to La Mere’s, but these issues remain real and raw. Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan refuses to hear Duwamish Tribal Chairwoman Cecile Hansen make her case for federal recognition. Meanwhile, other tribes, guarding their casino and fishing rights, are wary of recognizing the Duwamish and further dividing the meager pie.

Seattle’s early white residents prevented the Duwamish people, first signatory of the Point Elliott Treaty, from gaining a reservation in the 1860s because river-valley lands made available by treaty were deemed valuable pathways to coal. When Judge George Boldt made his decision, benefits accrued only to recognized reservation tribes.

Native groups still struggle for treaty promises made, in the case of the Duwamish, 160 years ago. Elected officials find it politically advantageous to stand on white privilege rather than justice. Nonetheless, the treaties are legal documents requiring political enforcement. As Haida / Tlingit Liz Medicine Crow writes, this “means the US has to be honorable.” Still waiting.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.