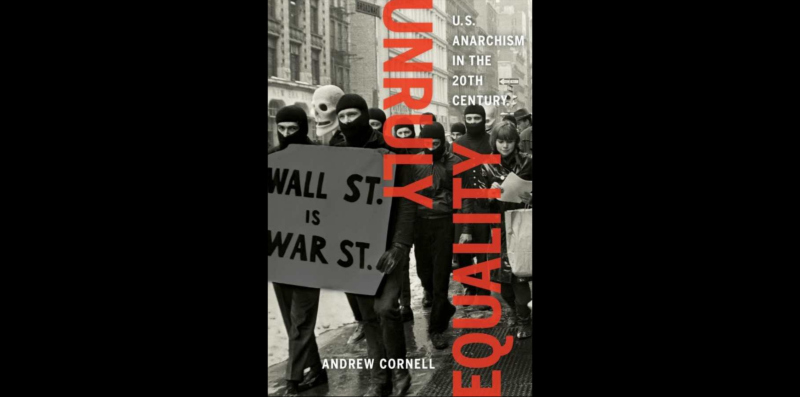

By writing an insightful, accessible and thorough history of 20th century anarchism, Andrew Cornell has made an important contribution to understanding the great social movements of that era. “Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the 20th Century” (University of California Press, 2016) can help inform current activists, historians and the general public about the contribution of anti-authoritarians to such movements as the mass labor struggles of the 1910s, the Black Freedom Movement of the 1950s and the New Left of the 1960s.

Anarchism is a political philosophy that emerged out of the great workers’ movement of the 19th century. Early anarchists broke with Karl Marx and his socialist adherents over the issues of hierarchy, power and the state. Anarchists believe that a truly egalitarian society can only be created by equals who eliminate all forms of domination including government.

In his history, Cornell makes important distinctions between the different kinds of anarchist philosophy and tactics that were present in the U.S. from 1900 to 1970. (An epilogue briefly surveys contemporary anarchists including the Occupy movement, but a real history of 1970-2000 is still needed.)

The first distinction Cornell makes is between individualist anarchists and social anarchists. Individualist anarchists and right-wing libertarians, such as Ayn Rand, are concerned with the self and individual liberty. Social anarchists, like Emma Goldman, Dorothy Day and Abbie Hoffman, are people who believe in acting collectively for social change without resorting to top-down organizations. Cornell’s history is only concerned with social anarchists.

Social anarchists themselves come in dizzying variety. Cornell divides them into categories, which is helpful but also problematic.

Insurrectionary anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists

He says the primary categories in the early 20th century were “insurrectionary anarchists” and “anarcho-syndicalists.” While both were primarily concerned with the struggle of the working class against capitalism, they posited very different means to achieve liberation.

Insurrectionary anarchists believed that capitalism would be overthrown by a spontaneous violent revolt by the workers. During that revolt, the workers would reorganize work along egalitarian lines and create a utopian society.

The main proponent of these ideas was Vermont’s Luigi Galleani, publisher and editor of a newspaper with a circulation of 5,000, whose message resonated with Italian-American anarchists, who organized into small, tight-knit groups in dozens of cities across the country. While Galleani is little known, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two of his passionate adherents, are among the best-known anarchists in American history. Unfortunately, their notoriety is due to Massachusetts unjustly convicting and executing them for armed robbery in 1927.

Galleani believed that anarchists could trigger revolution by performing “propaganda of the deed,” politically motivated assassinations and bombings. In the 1910s, insurrectionist anarchists carried out a string of bombings including simultaneous explosions at the homes of judges and politicians in seven Northeastern cities on June 2, 1919.

Previous and subsequent anarchist assassinations of U.S. President William McKinley and Archduke Franz Ferdinand (triggering World War I) cemented the mass-media representation of anarchists as apostles of violence.

The same period, Cornell writes, featured the emergence of a vibrant anarcho-syndicalist movement. Anarcho-syndicalists believed that labor unions could be the basis for revolution against capitalism and the construction of a new society built on freedom and mutual aid. A truly free society, anarcho-syndicalists argued, would have unions running the economy and replacing the government.

The best-known example of U.S. anarcho-syndicalism is the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) aka the Wobblies. Founded in 1905, the Wobblies broke with the American tradition of “craft unions,” represented at the time by the American Federation of Labor. Craft unions discriminated based on race, ethnicity and skilled labor. In contrast, the Wobblies welcomed all workers regardless of skill, national origin or color. Craft unions quietly negotiated with the bosses for better working conditions and pay. The Wobblies advocated work stoppages, industrial sabotage and nationwide or general strikes. Moreover, the stated aim of the I.W.W. was organizing “the new society in the shell of the old.”

The Wobblies weren’t purist in any fashion, so their membership included socialists, communists, anarchists and working stiffs.

Bohemian Anarchism

America’s most famous anarchist was Emma Goldman. In her early days, Goldman was mentored by the insurrectionist Johann Most. In 1892, Alexander Berkman, Goldman’s lifelong comrade, performed “propaganda of the deed” in his attempted assassination of the steel magnate Henry Clay Frick. As Cornell notes, Goldman never repudiated political violence. So, is she an insurrectionist?

After 1905, Cornell argues, Goldman advocated anarcho-syndicalism. Yet Cornell freely admits that Goldman transcended the limitations of anarcho-syndicalism with her advocacy of feminism, gay rights, child-centered education and artistic modernism. These tenets have been a tremendous influence not only on the contemporary anarchist movement, but also on broader protest movements such as second-wave feminism, queer liberation and political art including punk. Therefore, while Cornell places Goldman and her comrades under the banner of anarcho-syndicalism, he also gives them a sub-category of their own: bohemian anarchism.

Cornell’s sub-category of bohemian anarchism does not convincingly take into account the complexity of Goldman and her allies’ views. Neither does it help understand how Goldman’s ideas helped spawn social movements that grew far beyond anarchism’s banner. Despite these objections, Cornell’s distinction between insurrectionists and syndicalists is very useful not only in understanding the political dynamics of the 1910s, but also in seeing how these ideas influence today’s anarchist thinkers.

In my view, Oregonian John Zerzan’s anarcho-primitivism is basically an updated and expanded insurrectionism; Professor Noam Chomsky’s belief in building organizations that fight against capitalism and offer alternative structures to the current society has its roots in anarcho-syndicalism.

The strengths of Cornell’s analysis far outweigh its weaknesses. His stellar research and writing ought to inspire others to write and think in this rich tradition of political thought.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.