Karl Marlantes went to Vietnam as a young Marine officer, fought and survived some of the war’s nastiest combat, and five decades later delivered a masterful novel of that war, Matterhorn. The novel has been cited by critics as perhaps the most credible and probing writing from that traumatic time.

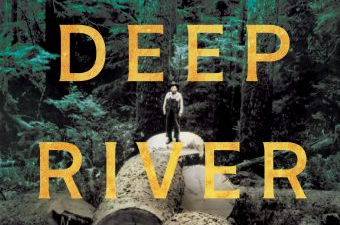

Marlantes has just produced another gem, this one much closer to home but equally sweeping and credible. It examines the tough and dangerous world of Pacific Northwest timber at the turn of the last century. Deep River (Grove-Atlantic, 2019) does for this giant slice of our history what Matterhorn did for the Vietnam War. Like his first book, this one is based on his personal history—in this case, that of his Finnish forebears.

If Norwegians and Swedes laid down the legends of the Puget Sound country, Finns were their counterparts in southwest Washington and northwest Oregon in lands drained by the mighty Columbia. Marlantes, in Deep River, stands on the broad shoulders of his own Finnish ancestors in a majestic 725-page novel that deserves a place on the shelf with Ken Kesey, Nard Jones, Ivan Doig, and Murray Morgan. Yes, a four-inch thick hardback can be a page-turner.

The novel is set in southwest Washington along the Naselle River, north of Astoria, the Oregon terminus for Lewis and Clark. Other place names are fictional, but easily recognized by those who know the country. It opens in 19th century Finland, then controlled by Russia but simmering with radical socialists, communists and Finnish nationalists. The Koski family is caught up in the turmoil and all three children ultimately wind up in the logging country of southwest Washington, driven out by the violence and a need to find a land of opportunity.

It is the middle sibling, fiery and stubborn Aino, a young woman with a radical streak and an amazing ability to lead and organize, who immediately seizes our attention. Rare in histories and novels of this time and region, this young woman demands respect, incites hatred, and causes tragedy both for those she loves and for herself. As an organizer for the radical Industrial Workers of the World, the infamous Wobblies of the early 20th century woods and mills, she is a heroine along the lines of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Mother Jones.

The brute force of early logging in the towering Douglas Fir and spruce forests stands in stark contrast to the dogged efforts and commitment of the Finnish immigrants to build a church and community in the harsh land, raise children and bury victims of the dangerous work and terrain. Marlantes has mastered the world of the woods of this era, with its appalling living conditions and body-breaking physical labor. The bailing-wire technical innovations of loggers and the ruthless pressure from owners and camp bosses give credibility for readers who know the history of the Northwest woods.

My reading of Deep River is enhanced by my wife’s history as the grandchild of a Scottish immigrant who came across the line from Canada with an ax and 20 dollars and built a logging company in this same area, employing many Finns in the process. His camps treated his men better than those in Deep River, but he was a Skookum driver as well, a pioneer in the high lead line and the splash dam. Marlantes’ prose rings true to those who heard the tales as young people in the Pacific Northwest.

Two novels and two classics: quite a sweep for this son of the Pacific Northwest. Deep River is a must read to understand an important part of our regional heritage.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.