The United States Department of Energy has announced it will soon start pumping highly radioactive waste from 10 single-walled steel tanks at central Washington’s Hanford Nuclear Reservation into double-walled tanks. This is a good step. But it won’t make those wastes safe for the long term, much less get them out of Hanford. Actually, the long-term prospects have some people pretty worried.

The Trump administration wants to redefine Hanford’s high-level radioactive waste as low-level. Does that make anyone feel safer?

Certainly not the Washington Department of Ecology’s Hanford operations manager, Alex Smith. Smith says she doesn’t know what the feds have in mind. They “refuse to talk about what their intentions are,” Smith says.

Long-time Hanford watchdog Tom Carpenter, executive director of Hanford Challenge, is afraid he knows exactly what the feds are thinking about the tank waste. The reclassification “is huge,” Carpenter says. “It’s the whole game. What they want to do is more than just relabel it. They’d like to dump concrete on top of it . . . and just walk away.”

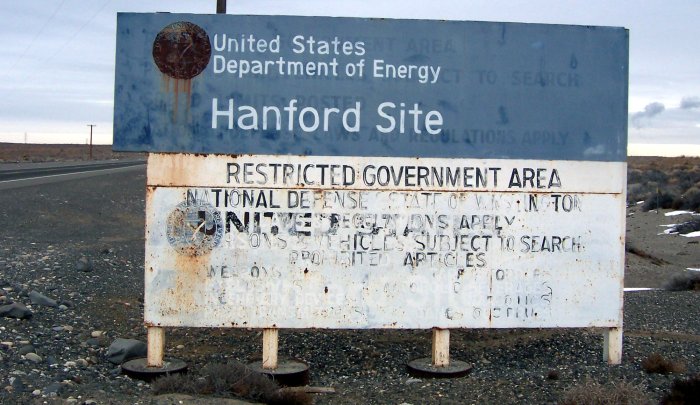

Stuck off in the arid, shrub-steppe landscape beside the Columbia River, largely out of Seattleites’ sight and out of mind, Hanford is, of course, the place at which people made the plutonium that exploded at the Trinity test site in the first man-made nuclear explosion, the bomb that destroyed Nagasaki, and the bombs that Strategic Air Command bombers carried around during the tensest years of the Cold War. As the first plutonium factory in human history, it is arguably the most significant historic site in the Northwest. It is unarguably the most heavily contaminated radioactive waste site on the continent.

And it will remain so for a long time. Billions of dollars have been spent to take out Hanford’s radioactive garbage since plutonium production stopped there in 1988. The cleanup, a multi-billion-dollar annual business in the Tri Cities, is governed, more or less, by a Tri Party Agreement signed 30 years ago by representatives of the state Department of Ecology, the federal Department of Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Under the agreement, federal contractors have already dealt with a great deal of low-level waste.

But high-level waste, 56 million gallons of sludge that contain radioactive elements mixed with ill-understood stews of toxic chemicals, remain in 177 tanks. To deal with those tank wastes, the government is supposed to build a vitrification plant that would incorporate the wastes in glass logs that would then be shipped to a deep geological repository under Yucca Mountain in Nevada. The “vit plant” was originally supposed to start operating in 2011. Now, it may start up in 2046. Or not. A lot of people figure it will never be built, and if by chance it is built, that it will never work.

Meanwhile, some old Hanford infrastructure is crumbling sooner than expected. Two years ago, part of a waste tunnel connected to the massive and heavily contaminated old PUREX plant, in which plutonium was extracted from reactor fuel rods, collapsed. This July, a report suggested that the PUREX plant itself, not scheduled for cleanup until the 2030s, posed a risk. And the waste tanks aren’t getting any younger.

The dollars aren’t keeping pace. The Tri Party agreement requires the Department of Energy to budget enough money for the cleanup, Smith explains. It does. Then the White House budget pares that original number down. Congress restores some but not all of the original funding. “Over time,” Smith says, “they’re falling increasingly farther behind.”

Catching up looks harder than ever. Three years ago, the Department of Energy estimated the total long-term cost of cleanup as $107 billion. This January, the department raised that to a minimum of $323 billion, a maximum of $677 billion. Energy secretary Rick Perry called the higher number “pretty shocking.” Indeed. Some people figure that was the point. “We feel like the low number there is actually kind of realistic,” Smith says. But the high number, she suspects, represents an effort “to intentionally inflate the cost.”

No one really expects Congress to appropriate two-thirds of a trillion dollars for Hanford cleanup, not even spread over 75 years. Set the barrier high enough, and of course the government has to come up with Plan B. Cue the effort to reclassify waste.

A new plan is also needed for the long-term disposal of those wastes, even if they do eventually wind up in glass logs. They were supposed to spend eternity in a deep geological repository under Nevada’s Yucca Mountain. But many Nevadans didn’t want them. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada didn’t want them. Barack Obama did want Nevada’s votes. The Yucca Mountain project soon lost its funding, its organization, its political support. A commission was told to come with alternatives to Yucca. It did: Find some state that wants the wastes and then do something or other with them. In other words, there is no plan.)

The nation has spent something like $9 trillion on developing nuclear weapons, Smith says. In that context, even the higher estimate of cleanup costs doesn’t look so steep. (Taken all at once, it would represent more than 90 percent of a year’s Pentagon budget, but on an annual basis little more than 1 percent.

Steve Gilbert of Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility argues that cleanup costs should be part of the Defense Department budget. Offloading those costs onto the Energy Department just provides another way to avoid the full lifecycle costs of weapons and wars — rather like offloading the costs of long-term veterans’ care onto the VA. Did anyone publicly consider those costs when the U.S. launched its wars in the Middle East? Of course not.

As it is, taking out Hanford’s radioactive garbage is a bit like cleaning up after a big party. The party’s over. Almost everyone has gone home. Who really wants to deal with this leftover crap?

The process has already “taken so long,” Smith says, “it’s easy for people to lose interest.” And why not? At best, by the time some of that radioactive waste is vitrified – assuming it ever is — it will be more than 100 years old. The energy department says the process may last into the next century.

As citizens of the United States, “all of us are responsible for the waste,” Gilbert argues. “How many generations is it going to take?” Well, let’s see: A generation spans about 30 years. The radioactive half-life of plutonium spans about 24,000. We’re beyond Biblical here. You do the math.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.