Shhhh . . . there, there . . .it’s all right. Breathe deeply . . .now tell me: what kind of quake?They come in different flavors, and each flavor has its own distinct characteristics.

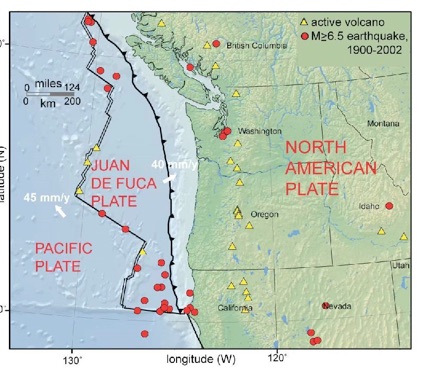

The kind that gives seismologists and emergency planners nightmares is the subduction quake. In our region, they release their energy directly toward the coast, causing both subsiding shorelines and tsunami-scale tidal waves. On New Year’s Day 1700, geographers tell us, the entire coastline from northern California to Vancouver Island was inundated (See map: we’re talking about the entire area behind the spiky black line from Eureka, California to the Port Hardy at the northwest tip of Vancouver Island: 700 miles as the crow flies, more than a thousand if you follow the coast.

Geologists have found evidence of such cataclysms (flood deposits deep inland, drowned and buried forests, etc.) occuring on the average every 500 years, but at such vastly different intervals as offers no confidence at all about when we’ll see the next.

No comfort there; but there’s no reason to get excited any time a big offshore quake rattles the teacups in Salem and Portland, as one did this morning at 8am local time. The reason for calm? The very great majority of offshore quakes in our region occur through a totally different and strictly localized mechanism.

Strike-slip events happen when two thin slabs (thin here being 5 to 20 miles thick) slide past one another under the stress of grander rearrangements of the earth’s crust. The vibrations from the grinding spread out laterally through in all directions, with comparatively little transmitted to the water-column above them.

Since energy in an elastic solid diffuses as the inverse square of the . . let’s just say that if Point B is twice as far from the original shock at Point A, the energy is only a quarter as powerful, and at Point C three times as far away only a ninth as great, etc.

In the great subduction quake of 1700, all the energy was directed straight at the coastline, with a mighty breaking wave church-tower tall falling on a beach suddenly meters lower than it had been minutes earlier.

It will happen again, and bloody hell when it does. But don’t lose much sleep about what’s shaking underwater in these parts. Save your nightmares for the next jolt on the Seattle Fault, where a vertical slip left a beach on the south end of Bainbridge Island hanging 20 feet above the waterline, and hundreds of acres of Mercer Island forest vanished beneath the waters of Lake Washington. (It’s still there, still standing.)

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.