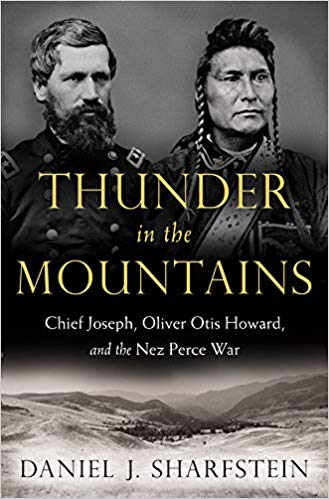

I recently finished Daniel Sharfstein’s magisterial 2017 work, Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard and the Nez Perce War. Sharfstein, a professor of history and law at Vanderbilt, joins a host of historians, novelists, biographers, and poets who have been inspired to write about the Nez Perce.

“Nez Perce,” meaning “pierced nose,” was a name given to this people by French explorers, but it wasn’t their name for themselves. They were, and are, the Nimi’ipuu, meaning “the real people.” Moreover, the Nez Perce were less a single, monolithic tribe than several loosely affiliated bands. “The Joseph Band” lived in the Wallowa Valley in northeast Oregon part of the year, descending to the more protected Snake and Imnaha River canyons in Oregon and Idaho for winter.

Fascination with the story of Joseph and the Nez Perce has proven lasting, with Sharfstein’s contribution to the literature one of the best of recent works. But why has this story proven just so compelling? I can think of at least seven reasons for its enduring power.

First, the character of the Nez Perce themselves. Many of the early white explorers, including Lewis and Clark, noted that the Nez Perce stood out among native peoples for their quality of life and culture. “Joseph and his people,” writes Sharfstein, “nurtured a set of ways to live properly as well as a strong sense of right and wrong.” This was evident in their interactions with whites. The Lewis and Clark Expedition staggered out of the Bitteroot Mountains of Idaho in the winter of 1805 just barely alive. They would have failed in their quest without the aid and the sanctuary provided by the Nez Perce. Subsequently, the Nez Perce evidenced remarkable restraint in the face of provocations from white settlers and constantly shifting government policy.

Second Joseph, whose name, Heinmot Tooyalakekt, meant “Thunder in the Mountains,” was an especially powerful embodiment of the Nez Perce qualities of a strong moral compass and spiritual depth. Tall and striking, Joseph wasn’t primarily a warrior or war chief, but a spokesman and advocate for his people. He left all who encountered him impressed by his dignity and resolve. Always his quest was to find a way to live with the white settlers. In doing so, Joseph often turned against the white settlers the words and concepts of the whites and U.S. government, such as “liberty” and “equality.”

Third among reasons for the continuing power of the story is the fact that even Joseph proved unable to manage peaceful co-existence with the influx of white trappers and prospectors, ranchers, and farmers. In the summer of 1877 a war began that took this band of the Nez Perce on an arduous 1,700-mile trek fleeing the U.S. Army under the command of General O. O. Howard. Howard’s job was to capture the band and force them onto a reservation near Lapwai, Idaho. Failing that, they were to exterminate these “non-treaty” Nez Perce. (Those who had agreed to settle at Lapwai and adopt a white way of life were known as “the treaty Nez Perce.” To this day a schism persists between the two groups.)

In the end, Joseph surrendered, as winter closed in, just 40 miles south of their goal, the Canadian border north of Montana. But before that surrender the Joseph band of the Nez Perce, probably numbering about 700, including women, children, and the elderly, along with extensive horse and cattle herds, eluded and confounded Howard’s soldiers time and again. Their courage and resourcefulness on that epic odyssey riveted the attention of people across the U.S. as did Joseph’s eloquence in surrender.

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking-Glass is dead. Ta-hool-hool-shoot is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who leads the young men is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are — may be freezing to death. I want time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. May be I shall find them among the dead. Hear me my chiefs: I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

His words, particularly that final sentence, became known throughout the world. At the time they were widely reported in the nation’s newspapers, and paved the way for Joseph’s remarkable post-war celebrity, a fourth reason for the endurance of this story.

In surrender Joseph and his band were promised they would have a portion of the ancestral land near Lapwai, Idaho. But like virtually every other promise of the U.S. government and its representatives, this one was broken. Thus began an eight-year exile that started in North Dakota, before taking them to hot and barren “Indian Country” in Oklahoma. In 1885 they were allowed to return to the Northwest not, however, to Lapwai but to the Colville reservation near Nespelem, Washington.

Chief Joseph, who died in 1904, never ceased advocating for his people and for their right to their ancestral homeland in the Wallowas. His advocacy took him across the country on numerous speaking trips to Washington, D. C. and New York, among other cities. He met with President Theodore Roosevelt twice. Everywhere he went he sought allies and an opportunity to tell the story of his people. “Some of you think an Indian is a wild animal. That is a great mistake. I will tell you all about our people, and then you can judge whether an Indian is a man or not.” Joseph moved many to tears with his oratory, but few to action. His band remained exiled to Colville, where his descendants live today.

Three mountains cradle the south end of Wallowa Lake. This glacier-formed lake acts as a reservoir for the Wallowa Valley, the ancestral land of the Joseph Band of the Nez Perce.

To the east (left in photo) is Mount Howard, to the west (right), Joseph Mountain. Between them Mount Bonneville, named for a French explorer. Joseph Mountain, extending northwest, is massive. By comparison, Mount Howard is somewhat dumpy, even forlorn, which is a fitting summation of how the two historic adversaries, Chief Joseph and General Howard, have fared in subsequent history. Joseph overshadows the man who defeated him.

General Howard is a fascinating figure in his own right and thus a fifth reason for the enduring power of the story of Joseph and the Nez Perce. He commands equal billing in Daniel Sharfstein’s Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard and the Nez Perce War.

Howard came to prominence — and lost his left arm to battlefield amputation — during the Civil War. After that war he was appointed to head “The Freedman’s Bureau,” charged with aiding former slaves to gain land and institutions to support their education and welfare. Howard University, the prominent historic black college, is named after Howard.

Someone forgot to tell Howard that in the corrupt administration of Lincoln’s hapless successor, Andrew Johnson, reconstruction was a farce. Howard took his work seriously, but was undermined by Johnson and his lackeys. He became a lightning rod for seemingly everyone’s ire. Thus an appointment to head the Columbia Department of the Army, and a move to Portland, were welcome.

The respite from the political wars of Washington D. C. was short-lived. Howard soon found himself again in the political crosshairs when charged to resolve the Nez Perce “problem.” Under tremendous pressure from Oregon politicians as well as his own boss, General W. T. Sherman, Howard was not without sympathy for Joseph and the Nez Perce. For a time he supported Joseph’s hope to retain the Wallowa Valley. In the end, Howard was caught in another no-win situation and ended up carrying out Sherman’s order to pursue the Nez Perce relentlessly.

Like Joseph, though to a lesser degree, Howard enjoyed post-war celebrity as a writer and speaker. In retirement, he returned to the task of establishing institutions for African-Americans, even as he sought to protect his reputation from those who portrayed his performance in the Nez Perce War as inept.

But Howard’s “caughtness” points to a sixth reason for the enduring power of the Nez Perce story. The Nez Perce too were caught, ensnared by formidable historical forces. The westward push of Euro-Americans that began with Lewis and Clark was followed by a rough and tumble legion of trappers and prospectors, the latter responding to rumors of gold in the Wallowas. They were followed by farmers and ranchers, some of whom, like Howard, were veterans of the Civil War looking for a fresh start.

Joseph maintained a hope for peaceful co-existence with the influx of whites on the Oregon Trail, but he stood against the odds. While some Euro-Americans were reliable partners and sympathetic to the Nez Perce, more railed against them as “savages” and called on the army to drive them to a “reservation.”

The destruction of one way of life in the face of the incursions of a new and more powerful one is not a story unique to the Nez Perce or even the indigineous peoples of North America. It is one way to describe what is going on the in the U.S. today, as the high-tech, digital economy transforms everything in its path.

Over the past 40 years, longtime residents of Wallowa County such as my family have seen another way of life — timber — come to end. For much of the twentieth century every town in Wallowa County was a mill town. Logging trucks rolled the roads and the mills were the major employer. Now, not a single mill operates in the county, though one continues in Elgin, in neighboring Union County. Another way of life came to an end, not so violently as for the Nez Perce, but still painful for those who had built their lives around it.

Beyond the logging industry, new pressures on a rural way of life persist in Wallowa County today. Tourism is growing. So too are the numbers of wealthier people from the west-side of the Cascades moving in and building expensive homes and taking land out of agricultural uses.

Which takes us to the seventh reason for the endurance of the Nez Perce story. Wallowa County has increasingly found itself in the Northwest and national media spotlight as an “undiscovered secret,” in the words of a Sunset Magazine cover story in 2016. The area has also been the subject of feature stories and op-ed pieces in the New York Times, among others. Meanwhile, the State of Oregon made the Wallowas one of the highlights of its “Seven Wonders of Oregon” promotion. Big picture ads on the sides of Seattle buses touted the Wallowas this spring.

With all this attention, tourism has grown and with it in the number of people introduced to the story of Joseph and the Nez Perce. Moreover, the presence of the Nez Perce themselves has been slowly growing. For despite what was arguably a genocidal campaign against them, they have survived, both in Lapwai and Colville. Many continue to practice their culture and traditions. They find a welcome today in Wallowa County at various cultural events and in a management role as Nez Perce Fisheries, now a major player in the county. This past spring elders from the Colville Nez Perce visited county schools to teach about the war and their culture.

The legacy of Joseph and the Nez Perce is larger still. Joseph was one of the first Americans to make the case for pluralism, for the possibility of different cultures and ways of life co-existing in North America. Whether or not the U.S. today will embrace or resist such pluralism is a, possibly even THE, contemporary question.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.