After a spirited hearing last week, the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board designated the 80-year-old Showbox Theatre building as a landmark, saving it, at least for the time being, from being torn down by the developer who bought it and a developer who wants to build a 44-story tower on the site.

But before anyone rejoices that a Seattle icon has been saved through the contrivance of a landmarks designation, the Showbox case is a good example of the feebleness of our approach to making and keeping Seattle a vibrant city. In a market heavily-weighted towards maximizing real estate profit, the cultural/social life of the city has few protections. Unlike land and building values, cultural benefits largely tend to be intangible and the real estate market routinely trumps them.

This isn’t an argument that the Showbox has an absolute right to occupy one of the most valuable parcels in downtown. Indeed, the theatre is increasingly out of place in the current landscape. But there’s no question that what goes on inside the building is an important — even critical — piece of Seattle’s identity. Can we really be so reckless as to casually threaten to throw it away?

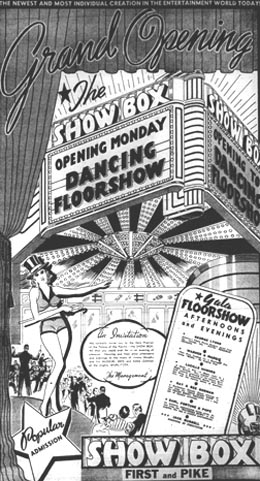

The landmark designation was a stretch under current rules. The building is neither beautiful nor architecturally important. It’s been added to and changed over the years. And it has a history of other uses – as a furniture showroom, a bingo hall, clothing store, peep show house and bar – that have obscured the building details. Though it was billed as an art deco showpiece when it opened, the “Palace of the Pacific” has long been stripped of its opulence and has spent long periods empty and neglected. Today it’s a utilitarian and architecturally unremarkable structure, a remnant from another Seattle. Hardly worth saving as a significant structure.

What it does have in spades is nostalgia. Jazz greats such as Louis Armstrong and Sarah Vaughan performed there. Quincy Jones is said to have bought his first horn in the shop in the front, and the space was important in the Grunge era when performers such as Sir Mix-a-Lot and Pearl Jam took up residence. It is one of those places in a city where people go to make memories, where distinctive cultural experiences help define what it means to live here.

We don’t know what to do with places like that.

Historical preservation laws were born of noble intentions. As cities grew and modernized, important architecture was being torn down. To try to save some of it and temper a market imperative that gives preference to the most-profitable use of real estate, landmark laws were created. Seattle once had 50 theatres operating downtown (in the 1920s), some of them ornate palaces. Only a handful remained by the 90s, and the Music Hall – at 7th and Olive – was the last to be torn down in 1992. The Coliseum Theatre was converted into a Banana Republic store in 1995. And the Moore, 5th Avenue and Paramount theatres were saved only through philanthropic largesse.

The laws have certainly saved countless historically important structures and we are the richer for it. But the landmarks approach to saving important culture is fundamentally flawed. It prioritizes saving pretty buildings which may or may not have continuing cultural use, over thriving culture which doesn’t come with an architectural dowry. Historic architecture that is no longer important for its historic uses is often saved, limping on as hollow shells, while important cultural spaces that thrive in crappy well-worn spaces are given the boot when developers eye opportunity.

The Showbox demonstrates the flaws in the saving-important-buildings idea. To save the Showbox, supporters had to contrive a case that it was architecturally important, while pulling heavily on the nostalgia threads. Its fate, in other words rests on its least compelling case. That’s backwards.

There’s another problem. Historic preservation laws impose real costs – sometimes cripplingly so – on those who are stewards of the buildings, often leading to real harm to the architecture the laws are meant to protect because they’re too expensive to maintain.

The famed Strand bookstore is a recent example. It’s a New York institution that has been around 92 years. Recently the city decided to landmark the Strand’s building, recognizing the importance the shop has had in New York’s cultural life. The Strand’s owner – a third-generation descendant of the founder – is furious, and believes that the designation will kill the business.

Why? Because that city’s landmark ordinance protects the architecture – which, like the Showbox, is unremarkable – rather than what happens inside. In a landmarked building, any activity inside the building is tightly regulated, adding significant cost and red tape to doing business there. Just what any bookstore needs, no matter how venerable. The building’s use as a bookstore – essentially the reason it’s been designated important – is encumbered and imperiled by having to serve the architecture, surely the opposite of what was intended.

There wasn’t a case under the law to save the Showbox because of its important culture or that it makes the city better. In grasping on to the landmarks route, the theatre will now also discover its options in operating the building are limited; saving it in this way came at a price.

As the city adds more glass towers this question of value is getting called more often. Most profitable use, the market has decided, is 40-story towers. But what kind of city mono-culture does that make?

For an extreme example, look at Venice, once one of the most powerful cities in the world, now a crumbling theme park with only a few thousand full-time residents and 20 million annual tourists who have taken over. In the 70s and 80s, as tourism grew, the shops and trades needed by working cities – plumbers, electricians, hardware stores, grocery stores, etc. were chased out by t-shirt and tchotchke shops, until it became a tourist mono-culture, a functionally unlivable city for residents who were left.

We don’t really have any hard definitions of what makes a livable or viable city, let alone a great one. So how many music venues does it take to make a great city? Bookstores? Movie theatres? Libraries? Parks? How about more mundane but essential uses – grocery stores, banks, coffee shops, restaurants? Golf courses?

Mayor Jenny Durkan recently floated the idea of redeveloping some of Seattle’s four municipal golf courses into low-income housing. It’s probably a good thing in the face of intractable homelessness to look at golf courses – some of the few remaining open spaces in the city – and wonder if there’s a better use for them. But there’s a reason citizens lobbied for and passed an ordinance to protect park space in the 90s, and that probably saves the courses.

There’s a tension between what’s most profitable for a developer and what’s most valuable for the rest of us. A developer clearly can make more money with a tower than with a theatre or golf course or almost any other use you can think of. Intangible benefits to a community, though real, are more difficult to quantify.

Partly that’s because culture often plants its seeds in unlikely makeshift spaces where the stakes are small. In the 90s, dozens of small theatre companies sprang up on Capitol Hill creating a thriving fringe scene. When cheap space got scarce, they melted away, as if they had never existed. The canyons of condos and apartments now lining Broadway have scraped away much of the area’s free-wheeling culture, just as they did in previously-weird Fremont. In recent years the CD is similarly losing its distinctiveness. It’s popular now to talk about food deserts or news deserts, places where there’s an absence of nutritious food or reliable news because the underlying infrastructure doesn’t support it. We’re in danger of creating culture deserts in which the distinctive personalities of neighborhoods are being subsumed into a generic mono-cultural norm driven by developers.

What if we landmarked uses rather than buildings? Fine, tear down this theatre, that community center, this coffee shop, but the deal is you have to recreate space or accommodate it somewhere. The problem, of course, is how do we decide what uses and what spaces are to be preserved? We seem to have done that with the 90s-era parks ordinance that stipulates no net loss of park space in the city. And we have city policies designed to encourage some activities (biking) and discourage others (cars) with the aim of making the city more livable. Recently we outlawed mega-houses and tried to encourage backyard cottages. Further back we saved the Pike Place Market. Hard to imagine contemporary Seattle without the market, yet in the 70s its survival was very much an open question.

But even landmarking uses is tricky. In Los Angeles, the iconic Amoeba Music record store on Sunset made a deal with a developer to move to another location. The developer plans to build housing – including affordable housing – on the current site. But critics are suing to save the funky building – which is only about 25 years old – to preserve its quirky character.

We don’t do a very good job of even defining what we need to be a vibrant cultural city, let alone encouraging it or protecting what we already have. Saving the Showbox was ad hoc. The Market was ad hoc. If it’s true that you are what you build, we seem to be all highrise office and apartment buildings these days. Impressive maybe, but hardly interesting. Some cities have designated cultural districts or cultural zones, encouraging cultural rather than commercial use. Seattle could do this, and there’s certainly a good case to be made for the contribution of culture to Seattle’s identity. Likewise, if we don’t do something more to make Seattle affordable for artists to live and work, we won’t have many. Perhaps Pioneer Square, home to distinctive architecture but – despite decades of effort – marginal commercial activity, could be one such area.

But defining what culture gets status is tough. It’s widely acknowledged in the arts world that there are cultural organizations that continue to live on after they’ve lost their relevance. Arts Council England has been struggling to set measurable standards of impact and relevance for the artists and arts organizations it funds (not successfully, so far). Major foundations such as Ford have refocused their efforts on cultural impact and equity. Organizations such as ArtPlace America have led the way in using culture to strengthen communities.

Clearly just being a theatre or museum or orchestra shouldn’t give you a preservation pass. We’re not good at letting cultural institutions die when they’ve outlived themselves. And important culture it isn’t just about arts. In my Montlake neighborhood we’re about to lose the Montlake Market, the area’s primary convenience store, to the next phase of the 520 bridge construction. It’s not a remarkable store, but it is an important one for the neighborhood, and neighborhood culture will be that much poorer without it.

The Showbox might have been saved for now. But why did it take extraordinary circumstances and cost to win the day? Why, in process-heavy Seattle do we not have a better process to value and protect (and even encourage) our important culture – be it theatres, markets, golf courses or grocery stores?

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One factual point — the Showbox has not been sold to a developer yet. There was an intent to do so, but after the Council intervened, the developer walked away, which then precipitated a lawsuit against the City from the current owner, who is demanding that the City be liable for the money he has lost. He’s asking for $40M, I think, and he may get it. The City Council got stampeded by Sawant (yet again) into enacting what was obvious at the time is in essence a blatantly illegal spot zone (which a judge has now confirmed).

Second, I’m genuinely curious, when was the last time the Landmarks Preservation Board voted against landmarking a building that was brought before them? My sense is the board is comprised of preservation activists who landmark pretty much everything.

Third, I’m skeptical this action — or the previous (illegal) actions taken by the City Council — have “saved the Showbox.” The landmarking thing may delay things a bit, but that’s all.

Thanks Sandeep. I’ve made the change regarding the sale.

Sandeep Kaushik’s comments about Landmark votes are lacking in a factual basis. First, there are buildings that are not required to be reviewed for Landmark status before they can be demolished; second, there are buildings required to be reviewed, but staff review determines their ineligibility and they do not go before the Landmarks Board; third, there are buildings that go before the Board and are denied (they often get limited publicity); and fourth even buildings that are nominated and designated by the Board may end up demolished because the law assures an owner a reasonable rate of return.

Douglas McLennan may want to contextualize the Showbox situation by framing it within Washington State’s legal “vested rights” doctrine. Washington State provides the strongest protections to private property rights of owners of any US state. The “vested rights” doctrine in Washington so strongly protects owners’ rights it makes it very difficult for public officials to negotiate compromises wth property owners. See Overstreet and Kircheim, SEATTLE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 23 (2000): 1043-1095, for a discussion of the issue from a very pro-developer viewpoint.

Thanks Jeffrey. I’ll look it up. Didn’t think about this from that angle. How is it that Washington got so tilted in this direction?

Douglas – WA State Appellate and WA State Supreme Court decisions in the early 1980s (particularly “Norco” and “Carlson”) significantly shaped land use law in this state. The extreme “vested rights” doctrine in Washington State is why Seattle’s Land Use Code is so complex; the Courts effectively decided that whatever is not explicitly prohibited is allowed. (It’s hard to give a more complete explanation within the limited space provided for comments.)

Douglas, thanks for the Showbox preservation story–which is not over until we know if the current use can be maintained. In the meantime, it’s my guess Seattle could go up against any city for effective preservation passion and activism. It’s just a shame we can’t translate that into formal designations, laws and incentives that could save places like the Showbox or other plain old (or not-so-old) buildings.