This week the Seattle City Council passed, each by a 7-1 vote, a pair of bills that set up separate funds into which the Sweetened Beverage Tax and Short-term Rental Tax revenues must be deposited, along with stricter rules for how the revenues may be spent — despite a threat from Mayor Durkan to veto the bills. A larger question, vexing cities that have enacted soda taxes, is whether they actually reduce consumption of sugar.

The votes were the culmination of a months-long argument about how quickly to enforce restrictions on spending from the two taxes, and in particular the Sweetened Beverage Tax. Durkan’s proposed 2019-2020 budget raided both revenue streams to cover a budget hole that both the Mayor and the Council had jointly made through decisions to increase spending on the homeless response and affordable housing programs.

Those are worthy causes, but outside the scope of how the Council had promised the community the revenues would be spent. But facing projections that show little revenue growth next year, the Mayor urged the Council to wait until 2021 to undo her budget sleight-of-hand — or at least until this fall’s budget process when they have better information on 2020 revenues and expenses. The Council, for its part, argued that they raised this as an issue last fall with the hope that it would addressed by March, and they felt obligated to reset spending back to the parameters of their promise to the most impacted community members.

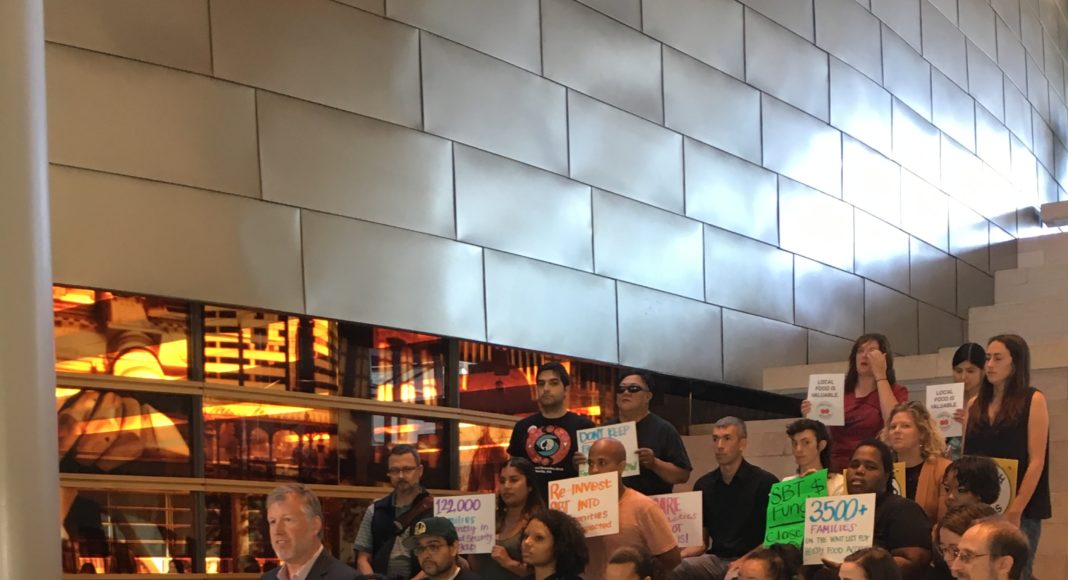

The $6.3 million of diverted Sweetened Beverage Tax revenues is tiny when compared to the $1.3 billion annual general fund budget and the $6 billion total budget for the city. Nevertheless, the argument over the Sweetened Beverage Tax (SBT) became heated over the last week, as the Durkan administration sent out scare-mongering letters to some human service providers telling them that the Council’s bills would put their funding at risk. That move backfired as the recipients of the letters huddled with the Council and organized a fervent rejection of the Mayor’s narrative, accusing Durkan of pitting human services providers against each other.

There were four amendments to the Sweetened Beverage Tax offered to the Council:

- a technical amendment with minor changes;

- an amendment from Councilmember Lisa Herbold which spells out in the recitals that it is not the Council’s intention to reduce funding for any programs, and directs the Mayor and Council to identify funds to cover the budget holes;

- an amendment by Lorena Gonzalez that clarifies whether prenatal services providers (such as home visiting, prenatal assistance and parent-child programs) are within the bounds of the spending rules;

- an amendment by Abel Pacheco to push out the restrictions until the 2021 budget, so as to give the Mayor and Council “flexibility” and time to find alternative funding sources. This was the only amendment that failed, by a 2-6 vote (Pacheco and Sally Bagshaw voted “yes”; Debora Juarez was absent today). While Pacheco said that he didn’t want to tie the city’s hands, Mike O’Brien argued just the opposite: that “we are intentionally tying our hands.” Kshama Sawant, ever the antagonist, stated that she doesn’t accept the idea of “fiscal responsibility,” and attacked Bagshaw for supporting the amendments. Bagshaw, clearly irritated, responded by pointing out that back in 2017 Sawant voted against enacting the SBT, while Bagshaw voted for it.

In the end, Pacheco was the sole vote against the amended bill. In his remarks, he pointed out that the conflict is the basis of several actions by both the City Council and the Mayor, asserted that they all share the blame, and said, “I don’t think the city wants us to play the blame game.” But during the roll call vote, Pacheco took a long pause before voting “no”. After today’s meeting, I asked him why:

“It was hard. I grew up in a black and brown household. I grew up on the food banks, on the early learning programs. I knew the importance of all these programs. You can’t pit them against one another. But I was trying to be consistent with my decision-making. It’s hard, it wasn’t easy. I mean, it was a series of decisions that took us to where we are, and I was trying to both be straightforward about just how I think we can best find the most responsible path to restoring the commitments that we had initially made.”

There were a few apologies offered by Council members after the vote. O’Brien, the bill’s sponsor, apologized to the communities for the time they took to get involved in this issue. Pacheco issued a general apology to the city for the mess. And Gonzalez said that the only apology she would make “is that we didn’t catch this when we passed the original legislation in 2017.”

Shortly after the vote, Mayor Durkan issued a press release expressing her “disappointment” with the Council’s vote, which she deemed “irresponsible.” she also committed to following through on her earlier threat to veto the two bills: “Because Council has refused to fund these vital programs or put forward a balanced plan, I will veto this bill.”

O’Brien also issued his own press release, doubling down on his earlier assertions that it’s up to the Mayor to solve the funding gap in a way that’s acceptable to the Council: “As the Mayor looks at all the revenue that’s available to her at this time and then sends us a budget, we will see what she prioritizes. I will say right now, if those revenues are disproportionately falling on low-income people to fund broad, citywide initiatives, I’m unlikely to support that.”

The Mayor’s veto is an empty threat; with seven “yes” votes, the Council has the supermajority required to overrule it. Then we will simply need to wait to see how the Mayor’s budget, when delivered at the end of September, addresses the funding gap.

What didn’t get much discussion by the Council was the lack of evidence that the soda tax is effective at its main goal: decreasing consumption of unhealthy sugary beverages. At a press conference this afternoon, Dr. Jim Krieger, head of advocacy group Healthy Food America and the co-chair of the city’s Sweetened Beverage Tax Community Advisory Board, said that “the sweetened beverage tax is working” in Seattle, claiming — based on as-yet-unpublished studies — that purchases of sweetened beverages have declined. He quickly diverted to talking about the results of Philadelphia’s similar tax, where studies have shown a considerable drop in soda sales that are partially offset by increased sales in neighborhoods just outside city limits. However, Krieger neglected to mention that the Philadelphia studies have also found no decrease in caloric consumption. Berkeley, CA, which has its own soda tax, also has found no decrease in caloric intake.

In Philadelphia, the soda tax has become a fierce political battle of another sort: whether to repeal the tax altogether, since it has led to lost jobs, broken promises of revenues to social programs, and unclear health outcomes. Depending on what the studies in Seattle show when they are eventually released, that may be round two of the city’s City Hall showdown over the sweetened beverage tax.

Can you create behavioral changes by taxing items people love to consume despite the health risks? Do smokers quit because of the price? It would be useful to see more research on the effectiveness of the soda tax, And if it does work and people drink fewer sodas, the city takes in less money.

“If you want to see less of something, tax it” is a popular refrain in government policy circles, and has been applied to alcohol, cigarettes, and through other “sin taxes.” And indeed, when the city first introduced its soda tax, it held 20% in reserve with the expectation that as consumption decreased, so would the revenues. But last year they got rid of the 20% reserve because there was no longer a belief in City Hall that consumption would decrease further. There is lots of hand-waving right now among city leaders who are saying that the fact that revenues are coming in much higher than expected is not a sign that the tax isn’t working, but more a sign that they didn’t have good data on sugary beverage consumption and underestimated the baseline.

The city is funding UW to study the impact of the soda tax. They already published a baseline study, and the first report showing sales and consumption trends since the imposition of the tax is due out at the end of the summer. That will be our first chance to understand what the impacts are. Unfortunately, with city officials heavily invested in the revenue stream now, no matter what the study says, it will likely be spun as “the tax is working.”

Is it just the dog days of summer, a time when news is slow, or are we witnessing the kind of small spat that can come to stand for a bigger debate? The Soda-Gate story has some elements of this: clash with Mayor and Council, continuing debate over spending for homeless services, the appetite for revenue at City Hall, promising the voters one thing if they pass a tax increase and then doing something else with the money. To these I would add another: How good are the programs that the soda-tax revenues are supposed to fund? Those programs are healthy-food and education-assistance programs in communities hit hardest by the tax.

Meanwhile, here’s Danny Westneat’s column on these issues: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/drink-less-soda-the-sugar-tax-is-seattles-fastest-growing-revenue-source-for-2019/