By Nick Licata and Roger Scott

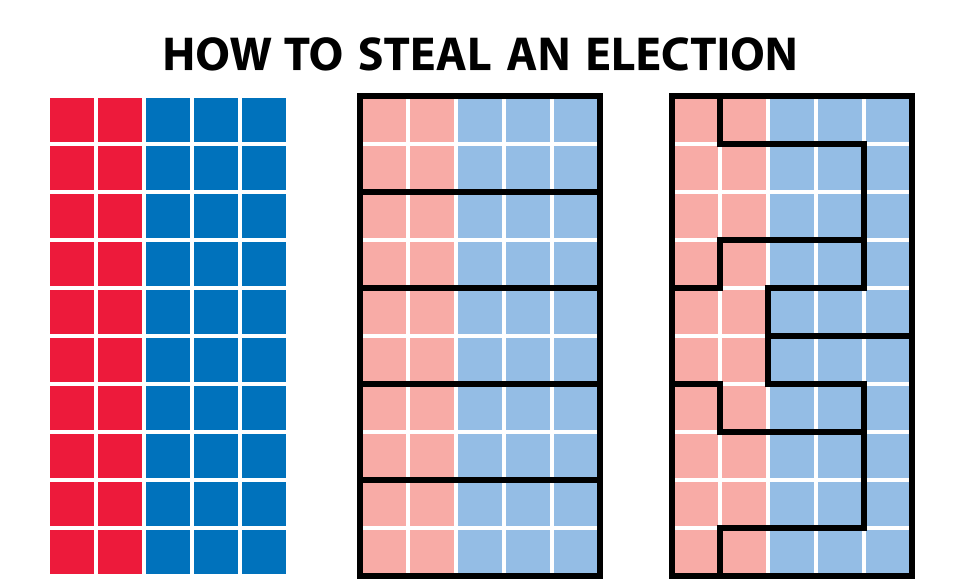

The Supreme Court recently gave the green light to 29 states (with 46% of the Congressional seats) to gerrymander Congressional and state legislative districts in 2021 as they draw district maps after the 2020 census. Gerrymandering locks domination of one party in a state for decades. In essence, politicians choose their voters instead of voters choosing their representatives. But there may be some ways to fight this practice, even though the Supreme Court took a pass.

For starters, citizens in the other 20 states (including Washington state) have received some or full protection from partisan gerrymandering by empowering nonpartisan commissions or (in Missouri) an independent demographer to draw the lines.

Historically, Republicans and Democrats have gerrymandered district boundaries to their extreme advantage. In Maryland Democrats won seven out of the eight congressional seats, while Republicans in North Carolina won 10 out of 13 seats, results that are well out of line with the actual turnout for each party. Republicans have used modern technology far more than the Democrats to finely tune gerrymandering by concentrating Democrat voters in the fewest districts.

Larry J. Sabato from the Center for Politics postulates that in light of the Supreme Court’s

redistricting non-decision states under one-party rule may be emboldened to more aggressive gerrymandering. This would be to the Republican’s advantage since they are in currently in control of drawing 179 districts to the Democrats 49. This trend will siphon political power from racial minorities. The president of the Brennan Center for Justice Michael Waldman noted that highly precise gerrymanders dilute the voting strength of an emerging nonwhite majority.

Citizens do not have to accept the Supreme Court’s gerrymandering decision. Former Attorney General Eric Holder, through his organization the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), is pursuing a strategy to focus on fighting gerrymandering state by state. He told a Mother Jones reporter this summer, “This is a recognition on the part of the

Democratic Party, on the part of progressives, that we need to focus on state and local

elections to a much greater degree than we have in the past.”

There are two distinct paths to fighting gerrymandering at the state level. First, they can use the initiative process to amend the state constitution. Second, make appeals to state supreme courts. In 2018 the voters passed state constitutional amendments to establish independent redistricting commissions in Colorado, Michigan, and Ohio; an advisory commission in Utah; and an independent demographer in Missouri. In 2019 another three states, New Hampshire, Virginia, and Arkansas, will likely authorize constitutional amendments to establish independent commissions. A citizen group in Oklahoma is working on an independent commission and plans on implementation in 2021. These commissions can draw new state legislative and congressional boundaries from the

2020 census, since the census data is scheduled to be released to the states by March 31,

2021, and by that time the commissions should have been established.

Most independent commissions consist of a set proportion of Democrats, Republicans, and independents who draw district lines under a transparent process involving all parts of the state. Lines must be drawn with objective criteria such as compactness, contiguity, respect of political boundaries (such as city and county lines) and preservation of communities of interest.

In 2018, voters approved independent commissions with large majorities (Utah excepted).

By including a robust number of independents on proposed commissions, frustrated

independents form coalitions with members of the out party to pass initiatives with large

majorities. The record shows that states with an initiative process can create an

independent commission in state constitutions regardless if they are red, blue, or purple

states.

Ten states have initiative power but currently have no protection against gerrymandering: Massachusetts, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming. Reformers could organize initiatives in these states to

emulate Virginia’s and New Hampshire’s successful effort to get their state legislatures to

authorize commissions. Citizen efforts in these states could use the support of presidential candidates, national public interest organizations and party national committees to help them launch initiatives to create independent commissions.

As for the 21 states that do not have initiative powers, citizens there could elect new representatives who would vote for a constitutional amendment that would allow citizen-introduced initiatives.

The second path is for citizens to bypass their state legislature and challenge

gerrymandering practices up to their state supreme court on the grounds that they violate

their state constitution.

Most states include language that is similar to that found in the Pennsylvania constitution

which says that “elections shall be free and equal” and no one shall “interfere to prevent

the free exercise of the right of suffrage.” The Pennsylvania Supreme Court based its anti-

gerrymandering decision on this language and the US Supreme Court’s majority agreed

with them. But Pennsylvania’s court decision was possible because new justices were

elected to their state supreme court, demonstrating that elections to state court positions

are too critical to ignore.

The states of Michigan, Pennsylvania and Texas, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Michigan and Ohio, which have been heavily gerrymandered, all have crucial state Supreme Court elections in 2020. Even though some of them have created commissions, it is necessary to protect their existence and performance by electing justices who will deflect challenges to those commission’s proper functions. Further, state supreme courts, if they wish, can redraw their congressional and state district maps in adherence to their state constitution, despite the federal court’s decision.

The above strategies can achieve a win for public accountability. This is an urgent matter since the states will redraw districts in 2021 or early 2022 and most of those will stick for a decade. The Supreme Court’s decision to allow states to continue unfettered gerrymandering can and must be rebuffed at the state level.

The following websites are useful:

https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/redistricting-

maps/

http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-criteria.aspx

Redistricting Reform Resource Center and the Brennan Center for Justice

Images: Wikipedia

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

My understanding is that WA’s redistricting commission contains equal numbers of Republicans and Demcrats and an Independent chairman who has no vote. It strikes me this is a recipe for collusion by the parties to protect incumbents and maintain safe seats-not the ideal kind of reform. Better would be an Independent chair with a vote. Or a non-partisan demographer.

BTW the national groups that helped state citizen activists get reform done in OH, MI, MO, CO and UT were Represent.us and the Campaign Legal Center. They are part of a huge national political reform movement working on, besides gerrymander reform, trying to get ranked order voting established in states beyond Maine, anti-corruption measures such as bans on lobbyists’ bundling, full contribution disclosure and facilitating small donor giving, plus trying to get rid of the Electoral College by interstate compact and reform of the FEC and Commission on Presidential Debates.

Mort, your concern with WA’s redistricting commission is one that is shared by me and many others. However, having been a politician, I recognize the best solution achieved is often not the best one possible. Ohio’s recent effort has been criticized on similar grounds. As you may be aware the Brennan Center has the most up-to-date assessment of the various state’s efforts and models adopted. Even with its faults, WA is still one of the best commissions going, we’d be very lucky to get a similar model in any of the southern red states without reformers taking over their state governments.