Last Friday, All Home King County released the results of the annual “Point in Time” count of homeless people. Its press release headlined the first decrease in homelessness in the county since 2012. The local media hopped on that headline, as did Mayor Durkan in her weekly “Durkan Digest” email newsletter to constituents.

After spending three days going through the report, I have come to the conclusion that not only is there little reason to believe the claim that homelessness decreased in King County, but there are also good reasons to view much of the data in the report with skepticism.

Let’s begin by reviewing what the Point in Time exercise is all about. The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) requires local jurisdictions who receive federal funding for homelessness programs to conduct an annual count of homeless people within the jurisdiction. That count must be conducted one night during the last week of January. HUD is prescriptive about the questions that must be asked and the categorizations that must be used for reporting the results back to the agency. All Home King County is the lead agency for the Seattle/King County “Continuum of Care,” and conducts the annual survey on behalf of the county. They contract much of the work to Applied Survey Research, an outside “social research firm” that does Point in Time counts for several other jurisdictions as well.

To supplement the one-night count, ASR also surveys a subset of the homeless population over the following weeks to drill deeper on a number of demographic issues as well as their experiences of homelessness in Seattle and King County. Those survey results are also listed in the report.

The one-night count is itself multiple efforts:

- The main count of people living unsheltered, which is conducted by about 600 volunteers spread across the county between 2:00am and 6:00am, assisted by paid “guides” who have experiences homelessness in the past and whose knowledge can help to locate homeless people where they hide off the beaten path.

- A separate count, conducted the day before, of unaccompanied youth and young adults. It is well documented that homeless youth are more adept at “hiding in plain sight” and more often will “couch surf” between the homes of friends, family members and other acquaintances, so finding them for the purposes of an accurate count requires different methods.

- A count of people who are homeless but sheltered: in emergency shelters, sanctioned encampments, “tiny home” villages, transitional housing, and other forms of temporary shelter. This is done separately through the providers who manage those shelters.

In 2017, All Home substantially changed its methodology for conducting the Point in Time count, rendering comparisons with earlier years meaningless. So with this year’s report, we now have three years’ worth of data using the new methodology and can potentially see longer-term trends.

Here’s the report’s top-level chart on the count of homeless people, broken out by whether they were “sheltered” or not and the type of location they were found in:

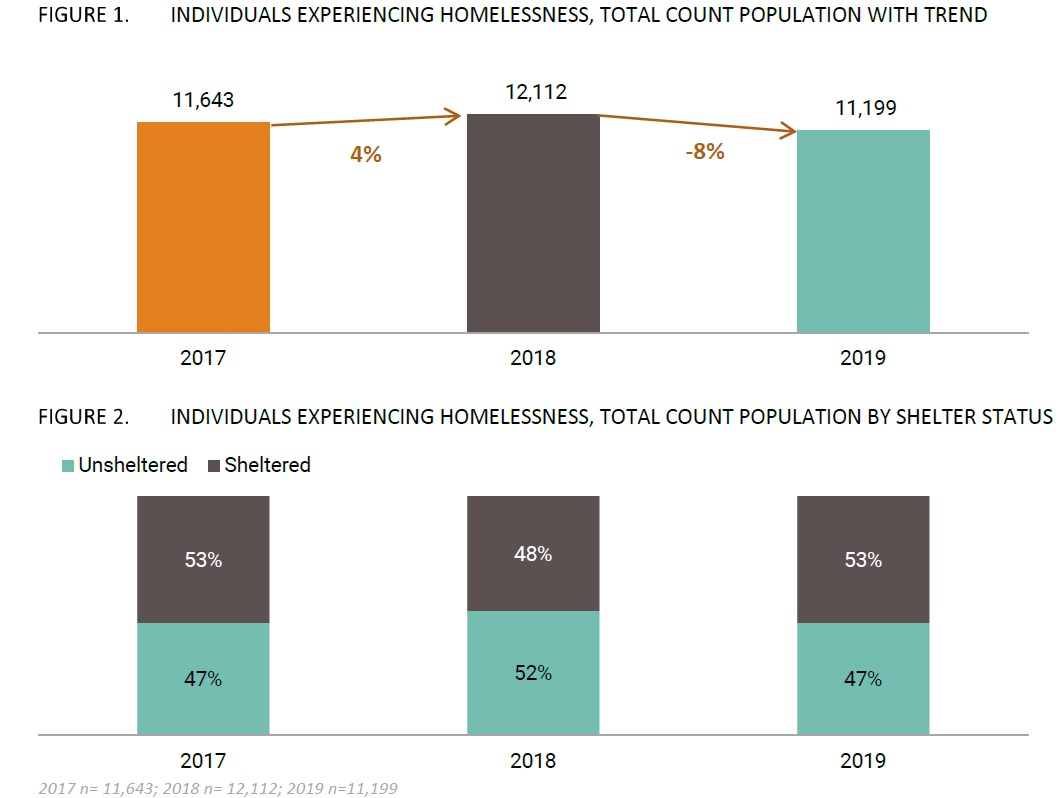

The report says that after a 4% increase in the total homeless count in 2018, there was an 8% decrease in 2019.

Some context is required for Figure 3 above and the “location type” data. In 2018, the City of Seattle added capacity in its emergency shelters — particularly “enhanced” shelters. Also, in the 2019 Point in Time report, the city’s “tiny home villages” were reclassified from “sanctioned encampments” to “emergency shelter;” this is a fairly trivial change, though some of the press reports call it out as a bigger deal (it would be a bigger deal if they had classified them as “permanent housing”). Together these two changes account for much of the increase in people in homeless shelters. The changes in the numbers of tents/unsanctioned encampments, vehicles, and transitional housing are more interesting. Unfortunately, the stacked charts are by percentage, not absolute numbers, so they don’t present a particularly useful picture of the shifts that have happened. Here’s a better graph:

Now we can see much more clearly where the year-to-year change happened in the overall numbers: a small increase in emergency shelter offset by a decrease in transitional housing, and a huge expansion in vehicle residents in 2018 followed by a dramatic decrease this year. That was offset in part by a small decrease in tents/unsanctioned encampments last year that bounced back up a bit this year. But clearly the big effect is the spike and drop-off of vehicle residents.

According to the data, over 1,000 new vehicle residents appeared in the county between 2017 and 2018, and then 1,200 disappeared over the last year. In the absence of any city or county programs that could have facilitated that kind of massive change, this is a glaring sign of problems in the data set. But there are plenty of other signs as well. For example, here’s what the age distribution looked like across the three years:

Look closely at the change in the 41-50 year-old group: a big drop in 2018, followed by a surge in 2019. That’s much more than one would expect to see from random sampling error. But it’s also inconsistent with what we know of the underlying demographics of the homeless community and of the most significant change that we saw this year: a dramatic decrease in people living in vehicles. According to the survey, the sub-population living in vehicles skews older that the rest of the population:

So if the number of vehicle residents actually decreased by 1,200 in the past year, the total percentage in the 41-50 age range would go down, not up. It would take an enormous increase in the age demographics for the rest of the homeless population — an unbelievable one — to compensate for the effect of dramatically decreasing the vehicle resident population. And speaking of vehicle residents, the survey also said that the percentage of people living in vehicles actually went up this year — directly contradicting the point-in-time count. A much more likely explanation is that the people in vehicles are now parking and spending the night in places where they are less likely to be noticed — and counted.

The breakout of the total count by region also looks weird. Several regions saw big spikes in 2018 that then returned to approximately 2017 levels this year, while the southwest region saw a big drop in 2018 and returned to 2017 level this year.

So what’s going on? Part of the explanation is that they changed their “multipliers” this year. Recognizing that the one-night count will always be an undercount (because they never find everyone living homeless), the actual tallies are multiplied according to best estimates of the percentage of homeless people reached. The team uses multipliers for different kinds of location-types where they know that multiple people tend to live but can’t count everyone individually. The same multipliers were used for 2017 and 2018, but this year, based on the survey results and comparable statistics from other jurisdictions, the multipliers were changed:

This is, in effect, a tacit admission that their estimates for 2017 and 2018 were off, though they didn’t bother to restate the numbers for past years. The adjustments to the multipliers explain most of the jump up in tent encampments in 2019, and some of the drop in vehicle camping. But when broken out by vehicle type, the change in RV’s is dramatic and not explained entirely by the multipliers (neither is the change in cars).

But there was another, even more significant, change in the point-in-time count methodology. Across the three years the number of volunteers and “guides” varied, with 2018 having the most of both.

Compare this to the yearly counts:

It should be no surprise that in 2018, the year they had the most people (and the most knowledgeable people) looking for unsheltered homeless people, they found the most, and they were a greater share of the whole homeless population tallied. It also could explain why there were far fewer vehicle residents tallied this year: if they have spread out across the county, having fewer people looking for them will exacerbate the undercount. Not controlling for the number of volunteers and guides year-over-year is a fatal methodology flaw; it would only be acceptable if it were possible to fully find and count all the homeless people in King County — which it isn’t.

This means that we really have no idea how many homeless people there are in King County, and we can’t draw any conclusions from the year-over-year changes. There is no credible evidence that there was a decrease in 2019; there’s also no credible evidence for an increase. The raw numbers of actual people counted during the Point in Time count in January established a lower bound on the true number, but we can’t estimate what the real number is. The count of homeless people who are sheltered is more reliable since we know how to find all of them, but that wasn’t a mystery that we needed a Point in Time count to tell us; the county’s HMIS system and the service providers’ records tell us that, plus much more useful information about the effectiveness of those programs.

Now let’s turn to the survey. They collected 1,171 surveys from unique individuals; if for a moment we were to believe the Point in Time count, then that would represent about 10% of the homeless population, more than enough to reach statistical significance. In fact, the survey firm asserts a margin of error (or “confidence interval”) of +/- 2.71% with a 95% confidence level. For smaller demographic subgroups within the survey, though, such as people living in vehicles, the chronically homeless, families with children, and veterans, the sample size is smaller and thus the margin of error is much greater:

For some of these subpopulations, the margin of error is so high as to make the numbers relatively meaningless — certainly too high to detect anything less than a dramatic trendline. But it’s actually worse than that, because this kind of calculation of confidence intervals assumes that sampling error is random, rather than the result of biases introduced into the sampling process. And on top of the biases we already know were introduced into this process, the survey data strongly suggests that it too suffers from sampling bias.

One example is individuals’ access to services:

Notice the similar pattern in the most frequently used services — even completely unrelated ones? They all dropped off significantly in 2018, then went back up to 2017 levels.

If we drill down into access to services for families (which granted has the highest margin of error), the results look completely different from last year’s:

Another example: the age distribution of homeless veterans. Here are the 2019 survey results:

Compare that to the 2018 numbers (note, the columns are swapped):

The 41-50 year age bracket jumped from 13% to 38%, while the 51-60 year age bracket went from 29% to 11%. There are other large demographic changes in the veteran sub-population that suggest sampling methodology problems as well, such as gender, where the gender-nonconforming count went from 10% to 18%:

These kinds of changes would have been more likely in 2018, when (to the extent we trust the numbers) the total count of homeless veterans dropped by 31%; it’s much less likely in 2019 when the decrease was much smaller.

There are other parts of the survey, however, that seem more consistent year-over-year, such as the data on the chronically homeless (though the male/female ratio did change dramatically in 2019). To the extent that certain issues are consistent across the homeless population — or even a sub-population, the survey can provide accurate results. The hard part, however, is knowing where to trust consistent year-over-year results, which could be misrepresenting a change just as easily as inconsistent results could be misrepresenting consistency in the underlying data. If the sampling errors were truly random, then the large sample size would compensate; but these kinds of changes and pendulum-swings suggest not only biases in the sample being surveyed, but probably also in how the survey is being delivered to individuals (such as the training level of the people asking the questions, or their familiarity with the persons being surveyed). And unfortunately we can’t tell if the answers are getting more or less accurate. If we knew and believed the “ground truth” from the Point in Time count, then we could use that information to validate the survey results, and re-weight them as necessary; but since we can’t really trust that data either, we’re left without much to go on.

In the county’s defense, keep in mind that the Point in Time count is mandated by HUD, and they are prescriptive about how it should be implemented. The report writers are also fairly transparent about many of the weaknesses of the methodology, and thus the conclusions that can be drawn from it (read the “Methodology” section of the report for more information). And yet, they still chose to lead off with a headline about how the overall count of homeless declined in 2019, knowing that it may not be true.

All Home, King County, and the City of Seattle also should be faulted for sticking closely to what is required of them in data gathering and analysis, rather than asking and researching the questions that would help us make better progress on the homelessness crisis. The city’s Human Services Department (HSD) has done the same thing with data around “exits from homelessness,” in which it sticks to a definition and reports required by the federal government that are not particularly insightful — and it has been criticized widely for publishing misleading statistics that make the department look more successful than it really is. Instead, the city and county could be looking at the “why” behind the statistics: assuming there was a surge of people living in vehicles in 2018 that disappeared in 2019, why did that happen, where did they come from, and where did they go? Where there are major demographic shifts, is it because of characteristics of the people entering the homeless system, or because the system in place make it easier for some people to exit than others? In places where the Point in Time count and survey results suggest the most worrisome trends (such as the rapidly increasing over-representation of blacks/African Americans among homeless families), what is the dynamic that is driving that and what specific interventions can be implemented to reverse it?

When I started analyzing the Point in Time report last Friday, I didn’t expect to conclude that the data, in aggregate, was not reliable enough to draw conclusions from — not just this year, but also back through 2017. And I don’t say that lightly now, knowing full well that it will provide fodder for those who want to generalize their own anecdotal experience with homeless people in their neighborhoods rather than trust data reported by authoritative sources. The story of homelessness in Seattle is a story of several sub-populations who experience it very differently: veterans, families, people with disabilities or chronic health issues, LGBTQ youth, and other groups. No one’s anecdotes from their neighborhood accurately describes what is happening with homelessness across this region. Just because one major source of data is found to be unreliable doesn’t mean we should replace it with a different unreliable source.

It’s also important to acknowledge the people who made sincere and efforts in generating the Point in Time report. A lot of people worked diligently and generously volunteered their time to gather the data from the report, and the raw data they collected tells important stories about the people living homeless in King County. And to the extent that the volunteers found a certain number of homeless people living in vehicles, or unaccompanied youth, or members of native tribes, or any other demographic with a tailored need, then policy-makers know that they need to provision services that meet the need for at a minimum that many people. That is valuable — and immediately useful — information, even if it doesn’t tell us everything that we want to know.

The problem with the report isn’t so much with the data that was collected, but with the data that wasn’t. We don’t know how many more homeless people went uncounted and un-surveyed, and we don’t know whether the data that was collected accurately represents them as well. And most of all, to the extent that things are changing — or unchanged — we still don’t know why. We can, and must, do better.

This article originally appeared on SCC Insight.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great job Kevin. And I see elsewhere there are now questions about the numbers after your story. This one by Sydney Brownstone, though, I find perplexing. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/homeless/did-chronic-homelessness-in-king-county-really-drop-38/ She asks the question about accuracy, and quotes a skeptic questioning changes in the methodology, but then doesn’t bore into it, leaving it hanging. It’s actually quite an odd piece.